Safe Space

Editor’s Note: This story has been reprinted from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Sixteen. Want to check it out in all its wonderfully-laid-out glory? Pick up this issue or subscribe today!

———

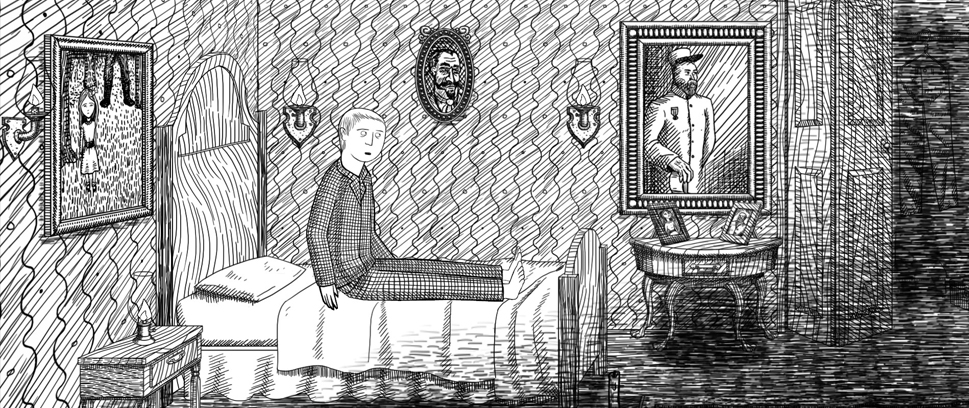

At first, everything seems fine.

A little strange, maybe, but the landscape that lays before you looks similar enough to what you’re used to that you should be able to adapt, but it’s not long before you start to notice something is wrong: The life is draining out of you. It’s small enough to not impede you at first. Then, before long, a feeling of malaise sets in.

Soon you have to rush to the next safe area to recover. Anxiety slowly creeps in. You frantically look for a place to get some relief. Spend too long looking for sanctuary and an alarm starts to go off in your head. Your vision begins to blur. Full-blown panic sets in. Something bad is about to happen.

If this sounds like a videogame, you’re probably not far off the mark. What I’m actually referring to is my own experiences with anxiety. It started years ago, on a drive home from a music festival. I had three hours to myself, it was midnight, I had copious amounts of Mountain Dew LiveWire and the music was blaring from my car’s speakers.

I was fine for the first couple hours, before the home stretch. At that point I could tell something was wrong. My heart started going funny and my limbs went numb. My breathing got heavier and heavier. Soon my vision started to fade.

I called 911. When the ambulance took me to the local hospital, they told me I had a panic attack. Ever since, I’ve been unable to go anywhere on my own without instinctively freaking out. Even traveling with other people proved difficult until very recently. I’ve been shackled to my home and surrounding area, only able to venture further with my parents – my safe spaces.

This world view is not unlike how most videogames are structured, built on danger and conflict and paced in such a way that players get a reprieve from these hazards every so often. Sometimes this respite comes in the form of cutscenes, towns filled with non-player characters or even just rooms without the threat of enemies or damage: these, too, are safe spaces.

It makes sense. You never want your game to be all tension, something entirely homogenous and unpleasant. It would be like locking the player in a hot box for eight hours.

Videogames feel uniquely suited to tackle subjects like panic thanks to their history and development structure. And yet somehow we see very few games actually use this ebb and flow of tension in a meaningful manner. Still, some embody this dynamic almost by accident.

The opening of this piece, for example, also happens to describe the dynamic of Dark Aether in Metroid Prime 2: Echoes. Unlike its predecessor, Echoes has two near-identical worlds you switch between as a means to progress through the game. But where Aether feels a lot like Tallon IV from the first game, its dark counterpart turns the planet into a truly alien world, with strange creatures attacking you at every turn. Most striking is the atmosphere, which will slowly drain the life from you as you’re exposed to it. The only way you can survive this harsh environment is by dashing between domes of light that are either already set up for you or that you create with a special Light Beam.

You can see where this mechanic works as a metaphor for panic and anxiety right away. The further you get from your safe space, the more in danger you are from something bad happening to you. Thus your journey through Aether’s other half is a frantic run from dome to dome. You stop for a few seconds – or sometimes minutes – in each dome, as you recover health whenever you do. Enemies will stop just short of the boundary. Even though the domes prove to be a haven and font of recovery, just standing there can make you feel trapped, shackled to one of the few spaces in the world that doesn’t want to see you dead.

It’s a feeling I’m certainly familiar with.

Sadly, this element of danger and tension ceases not long into Echoes. After clearing the first area and retrieving Samus’ Dark Suit, the drain on your life is rendered nearly inconsequential. Nor do you ever feel all that threatened or panicked when you’re armed with beam weapons, missiles and protective armor. Thus Echoes reveals the limitations of videogames as an exploration into the psychology of panic – or at least, the way games have been traditionally made until recently.

Where Echoes falls particularly short in any analog to anxiety is in its role power and control play. When I’m attempting to travel alone, the panic I feel stems from the fear that I’m going to pass out while I’m driving or in a strange place. Passing out leads to worse things, and therefore must be avoided. But you can’t avoid it. You have no control over it. It’s an anxiety the comes from a fear of losing control of yourself.

Games aren’t usually concerned with taking away control by their very nature. They empower the player to be able to perform amazing feats like shooting grotesque enemies until they vaporize, jumping across huge chasms or rolling into a ball and clinging to walls and ceilings. You may have to dart between light domes to survive at first, but this notion of vulnerability isn’t real. In Echoes, and most games, you never leave a safe space because you are one yourself. The mantra of games is interaction – taking away control from a player is nigh-unforgivable sacrilege.

The only possible exception to this is survival horror, where developers intentionally play around with measures of control and player agency to unnerve you. Take Silent Hill, for instance. Despite often finding real weapons like guns and knives, they’re often ineffective when faced with the horrors that wander in the darkness. The games often impede your control systemically as well, making something as simple as turning your character require you to hold down the d-pad in the direction you want to turn – survival horror’s infamous “tank controls.” Resources are also limited, so attempting to shoot everything or risk getting hurt too much isn’t wise. These conditions and rules leave you fragile and vulnerable.

This wouldn’t be possible without the concept of safe spaces. Like many survival games, Silent Hill typically requires you to investigate a great deal of compartmentalized spaces (like hospitals or apartment buildings) as you try to fumble your way toward the exit. The nightmarish monsters that populate many hallways may stand in the way of the rooms that contain keys and puzzles – many rooms don’t have enemies and you’re trained by the game’s internal logic to know that the ones outside won’t chase you through doors.

The realization may cause you to linger in these safe rooms until you’re ready to take on the hellish landscape on the other side of the door again. You know what waits for you on the other side, and you really don’t want to face it. Silent Hill is, after all, not a world that is fun to be in. And when you finally do venture out again, all you want to do is make it to another safe space, somewhere where you’re free from the otherwise pervasive horror. Somewhere you can feel in control.

Then there is Lone Survivor. Unapologetically inspired by Silent Hill, Lone Survivor takes the same formula and puts it into a 2D sprite-based game. You’re still faced with horrible enemies, forcing you to run between safe areas. And you still have to deal with limited resources, too, though Lone Survivor takes this to new extremes by forcing you to eat and sleep, lest you run out of energy or mental stability.

Not eating will cause you to starve and lack of sleep will dive you further into madness. You can stave off your drowsy state by taking specific pills, but your sanity will crash later, a dynamic that rings true with how panic works. What do you do if you can’t find your way to a safe space? You try to create one however you can.

Just as how I relied on caffeine to keep me awake as I drove home before my first panic attack, I became dependent on something to stay mentally OK in the time that followed. The result was I convinced myself that some episodes originated in undiagnosed Diabetes. I was just suffering from low blood sugar. This caused my brain to insist I always stay fed or face a repeat of that horrible night. I needed something, anything to keep me safe.

Games shouldn’t just stick to throwing up physical barriers when they have the power to tackle psychological ones. Panic and anxiety already feel like terrible games on their own, imposing heavy rules and limitations on our lives. The phenomenon is just tailor-made to be explored in game form.

While it’s obvious games prove it’s possible to explore these issues, there’s so much more ground to cover. If nothing else, games can prove eerily allegorical and even hopeful – at least to me.

When I’m bracing to open a door back into Silent Hill, I pause and contemplate never leaving my safe space. Nothing can happen to me if I don’t open that door. But if I’m just going to stay in there forever, then what’s the point of playing the game?

———

Follow Jeremy Signor on Twitter @SnakeofSilent.