Too Much Face Time

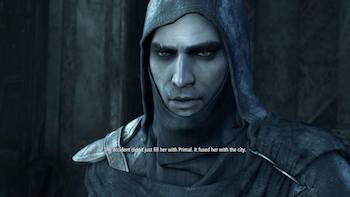

I was only an hour or two into 2014’s Thief reboot and the sight of its protagonist’s face was already beginning to annoy me.

It wasn’t the graphics (they’re beautiful) or Garrett’s relative attractiveness (eh) or that his expression never ever ever changes (maybe he’s hiding his feelings?). Garrett’s face annoyed me because I saw way, way too much of it. Because whenever I saw Garrett’s face I wasn’t playing Thief, the first-person stealth game. I was watching Thief, the movie. And Thief (the game) for all its many flaws is still way better than Thief the movie.

Most videogames at least start with cutscenes. Thief, however, makes the refreshing decision to simply jump immediately into Garrett’s life – players find themselves standing in a rich man’s bedroom ripe for the robbing. As the man snores in bed, we creep about his room, lifting valuables and learning how to pick locks. When we emerge from the man’s house onto the roofs, a young woman named Erin is waiting for us. Apparently the house we just left is small change – Garrett and Erin have to go deliver an item they stole for a wealthy client.

Most videogames at least start with cutscenes. Thief, however, makes the refreshing decision to simply jump immediately into Garrett’s life – players find themselves standing in a rich man’s bedroom ripe for the robbing. As the man snores in bed, we creep about his room, lifting valuables and learning how to pick locks. When we emerge from the man’s house onto the roofs, a young woman named Erin is waiting for us. Apparently the house we just left is small change – Garrett and Erin have to go deliver an item they stole for a wealthy client.

Now, instead of letting players control Garrett as he and Erin make their way to the drop point, the game suddenly hits us with a loading screen and then starts us off in front of the Baron’s mansion gates. That was the first warning sign in an otherwise great intro. We’re supposed to be embodying Garrett. Carving out a chunk of time from which we are supposed to be him, without giving any kind of narrative reason for the skip, is a sign of either budget cuts or a weak narrative that needs to use a stick instead of a carrot to keep players on track.

After following Erin through the grounds, Thief‘s main plot kicks off with a non-playable third-person cutscene wherein Garrett and Erin begin to squabble over her use of a climbing pick that the burglars call a claw. Garrett insists that she’s too dependent on it, Erin tells him he’s full of it. Considering that Garrett (and players) will depend on the claw for the rest of the game to reach high ledges, I’m inclined to agree with Erin. But I can’t do anything about it, because for the first time in the game Garrett is out of my control. I can do nothing but stare at his face.

This petty and ultimately meaningless disagreement leads to Erin falling off the rooftop and into the middle of a mysterious ritual, where a magical blue light appears to consume her. Garrett tries to save her, fails and falls in himself. This scene eventually becomes the impetus for the game’s main plot, as Garrett begins to search for answers about her accident. In other words, if Thief has one chance to make us buy into its story, it was this scene. And it failed — in large part because it used a cutscene.

Players have no input into the argument that led to Erin’s fall – no dialogue options, no alternate consequences based on our previous actions. Nor can players influence the fall, either. We’re not in control, so it isn’t our slow reaction time or insufficient skill that leads to her slipping out of Garrett’s grasp. Because this scene is a cutscene instead of playable, players are not personally implicated. We merely watch Garrett’s face as he acts, reacts and fails.

This part of Thief was particularly frustrating because we’ve seen a very similar scenario in a much better game: 2012’s Dishonored. In fact, Thief borrows so heavily from Dishonored‘s narrative that most journalists (myself included) pointed it out in their reviews. But while Thief copied Dishonored‘s aesthetics – a medieval steampunk city, a strange disease, class warfare, supernatural vision powers – it clearly did not understand why those aesthetics worked so well in the first place.

In both games a woman’s death kicks off the main plot. However, in Dishonored the scene stays in the first person perspective and is is playable from start to finish: as a player you think your job is to fight off the attackers, which keeps your intentions in alignment with protagonist Corvo’s own. But the story begins when both the player and Corvo fail. By putting you in Corvo’s shoes and then creating an unwinnable scenario, players are implicated in Jessamine’s death. Corvo’s mission to save Jessamine’s daughter Emily and “redeem himself” is personal for the player as well.

For the entire rest of the game, every action Corvo (and the player) takes is directly tied to this event. And Corvo’s strong motivation for revenge translates seamlessly into gameplay, in the form of carefully orchestrated infiltrations, espionage, and, if the player chooses, assassination. Thief immediately breaks with Erin’s death, instead having Garrett try to return to business as usual and ignore what has transpired. Not only is he completely incurious about the nature of her death (or why he assumes she died when he himself survived) but he doesn’t even seem that upset about it.

For the entire rest of the game, every action Corvo (and the player) takes is directly tied to this event. And Corvo’s strong motivation for revenge translates seamlessly into gameplay, in the form of carefully orchestrated infiltrations, espionage, and, if the player chooses, assassination. Thief immediately breaks with Erin’s death, instead having Garrett try to return to business as usual and ignore what has transpired. Not only is he completely incurious about the nature of her death (or why he assumes she died when he himself survived) but he doesn’t even seem that upset about it.

A weak plot can be forgiven so long as we’re the one playing it (hey, Skyrim!). But again, Thief faces the carrot-and-stick problem: it can’t quite figure out a plot that would give us a reason to play through its levels, so it removes any opportunity for player choice or interpretation, instead hitting us with cutscene after cutscene in which Garrett tries to explain his weak and abruptly changing motivations (followed by a sarcastic witticism). By the time Garrett gets back around to investigating Erin’s death, the levels feel like little more than the narrative herding us from cutscene to cutscene. Why are we going to Moira Asylum? To help Erin, somehow, probably! Just follow the checkpoint icon on your map! Eventually a cutscene will retroactively explain why you just did what you did, and then it’s on to the next level!

That’s not to say that cutscenes in videogames are always bad. One of 2013’s most critically acclaimed games, The Last of Us, made frequent use of third-person cutscenes in a narrative that was just as structurally linear as Thief. However, The Last of Us frames its cutscenes in a far more sophisticated manner. For one, the cutscenes and gameplay are both third-person, creating a visual and perspectival harmony between the two that makes the transition less jarring.

Further, many of the things that happen in The Last of Us‘s cutscenes are things that occur outside the protagonist Joel’s control. There is nothing he can do to prevent his daughter’s death that opens the game, just as Corvo cannot, even while under the player’s control, prevent the Empress’s. The inability to act is a part of the story itself rather than a consequence of clumsy storytelling.

Unplayability isn’t the only problem with Thief’s cutscenes. By wrenching us out of first-person and into third-person perspective and then back again, the game switches between the language of videogame storytelling and the language of film storytelling, never quite committing to either. The result is that it fails at both, producing a visual and experiential inconsistency that betrays the game’s insecurity with its narrative. It’s especially frustrating considering that Thief’s first-person gameplay sequences largely do a great job of making us feel like we’re in Garrett’s body. I particularly liked the way that the camera would shift as Garrett leaned forward to pick up items or hunkered down to peer over ledges. The motion gave a sense that, when we pressed buttons, a real body was performing each action.

But many games with strong first-person components still use third-person cutscenes. We’ve become used to them, and in a decent story they’re easier to forgive. Thief’s overall narrative weakness only highlights the flaws in a technique that has always been more about convenience than innovation.

Switching between perspectives could be an interesting narrative device, if the game utilized it to tell its story. The only example of an intentional switch between perspectives that immediately comes to mind is Assassin’s Creed IV. While the majority of the game – all of your time exploring the genetic memories of pirate Edward Kenway – is in third person, your time as the unnamed Abstergo Entertainment research analyst operating the animus is all in first-person, obscuring the character’s appearance, race and gender, t so that players may project their own identity into the game.

Thief is not doing anything on this level. Once more, it invites an unfavorable comparison with Dishonored, a game that uses its consistent first-person perspective to reiterate how much, or how little, Corvo truly understands about his situation. For example, in both games the girl whom the player must rescue (Erin in Thief, Emily in Dishonored) draws pictures of the main character, which players can find at various points during the game.

Thief is not doing anything on this level. Once more, it invites an unfavorable comparison with Dishonored, a game that uses its consistent first-person perspective to reiterate how much, or how little, Corvo truly understands about his situation. For example, in both games the girl whom the player must rescue (Erin in Thief, Emily in Dishonored) draws pictures of the main character, which players can find at various points during the game.

In Dishonored, these drawings are the only way players can see Corvo’s face, whose appearance alters based on how Emily sees you. If you murder and maim your way through the game Emily will draw you as a faceless angel of death; choose a more roundabout, merciful route and she will draw you unmasked and smiling.

In Thief, players can find many drawings that Erin has made of Garrett, too. But seeing Garrett’s face in Erin’s drawings has little emotional impact since we see it all the time in the cutscenes. And the drawings themselves don’t change because Garrett undergoes little emotional growth, either at the player’s choosing or in his own pre-scripted scenes. I’ve already seen way too much of Garrett’s face already – why are these drawings any better?

It can be hard to criticize videogame cutscenes, as expensive and labor-intensive as they are. But even the most beautifully rendered cutscenes are simply sutures holding together what’s most often a disjointed narrative, particularly in first-person games. Thief’s story had a great deal of problems, but its use of third-person cutscenes is the one issue to which I keep coming back. Because I spent way too much time with the controller held loosely in my hands, staring at closeups of Garrett’s face.

———

Follow Jill Scharr on Twitter @jillscharr. Header illustration by Chris Martinez.