Mindways

Two things I dread: decreasing the signal-to-noise ratio and being dishonest about how complex the world is.

Both of these are pretty paralyzing to a writer.

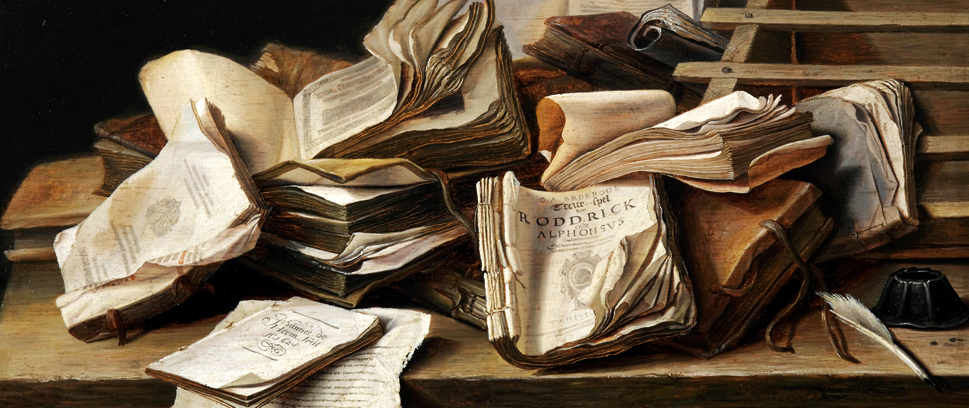

Writing is violent. To write about something you have to cut away all the things that can’t be written down, rip it away from all the things you don’t notice and all the things you don’t know how to capture. Then, if you’ve managed to get your hands on anything, if there’s anything left, you begin to pick it apart. Editors, how-tos, the voice inside your head, everyone tells you to find the essence, as if the only thing that matters is what can be written down.

Writing is a creative act, we’re told. In the West, writing is so powerful it created the world, as anyone familiar with Abrahamic religions can tell you. And those of us who spend too much time around videogames, with their roots in science fiction and fantasy stories where rules have to be set within the first 30 or so pages and then consistently adhered to afterward or risk being criticized for the dreaded inconsistency, well, we could be forgiven for buying into the notion of world-building.

Words aren’t even bones when they lie there and wait for a reader who has to try and put back what the writer rends. So maybe reading is the more creative act.

Alberto Manguel’s The Traveler, the Tower, and the Worm: The Reader as Metaphor puts the writer as traveler first for a good reason: rather than starting with the isolating ivory tower or the consumption-mad bookworm, he begins with the active traveler. The one who reads the word to better read the world.

Alberto Manguel’s The Traveler, the Tower, and the Worm: The Reader as Metaphor puts the writer as traveler first for a good reason: rather than starting with the isolating ivory tower or the consumption-mad bookworm, he begins with the active traveler. The one who reads the word to better read the world.

Manguel’s written several books about reading. It’s so smart! His audience is already people who look to books to find ways to explain and expand themselves. Of course, he’s also writing about writing, but writing for other writers is maybe a little too off-putting.

There’s lots in there about the spatiality of books, about how pages behind and pages ahead orient you as you read. For academics and journalists whose livelihood depends on being first with the truth, finding this book might have been a bad thing. They’d be scooped.

But this book clarifies and says what I’ve been trying to articulate for so long and I love it for it.

It’s risky, my talking about this book. But I want other people to read it and see if they get the same things out of it that I do because of a need for external calibration. The same reason I write these short-reaching words.

A longtime friend who edits for a living once told me about my writing that I try to recreate my thought process on paper, which is not the most efficient way to convey my point. Another told me I use too many parentheticals (which amounts to the same thing, if you’re me).

A longtime friend who edits for a living once told me about my writing that I try to recreate my thought process on paper, which is not the most efficient way to convey my point. Another told me I use too many parentheticals (which amounts to the same thing, if you’re me).

Thus: so many possibilities cut away because their complexity can’t be captured in words. Simplicity, “clarity,” they’re comforting and they’re what people look for. They’re what I look for. But they’re not what exist in my mind. And I can’t help but feel that if you provide a simple explanation when the reality is so messy, that you’re being a little dishonest.

Frank Conroy writes in his memoir Stop-Time about his stepfather’s rhetorical strategy: “All problems were reduced to a simple proposition…First, a slow and elaborate introduction to the subject at large, and finally, at the right moment, a sudden reduction to the essential. It was simple and remarkably successful — after the bewildering opening verbiage people grasped the cleverly introduced reduction with the tenacity of bulldogs.”

It’s a powerful strategy, and it’s tempting. There’s a big audience for that kind of thing (see: TED and Gladwell and “history” books with one-word titles), and you can look brilliant.

But I’ll let you in on a secret: my motives are selfish in a completely different way.

My mind works fast. Too fast, sometimes. I’ve got a very vivid imagination and while being able to filter through a variety of scenarios quickly is helpful for figuring some things out, it gets away from me.

If I can drag you along my mindways and you understand, then I’m going to be OK.

———-

Brian Taylor has more or less quit Twitter, but you can always email him.