Creating a Playground of Wonder

Scale is the freshest take on first-person perspective games I’ve seen since the original Portal. It is being developed by Steve Swink, who describes himself as a game designer first and foremost, but who also teaches game and level design, including master classes at NYU, and has published a book titled Game Feel: A Game Designer’s Guide to Virtual Sensation.

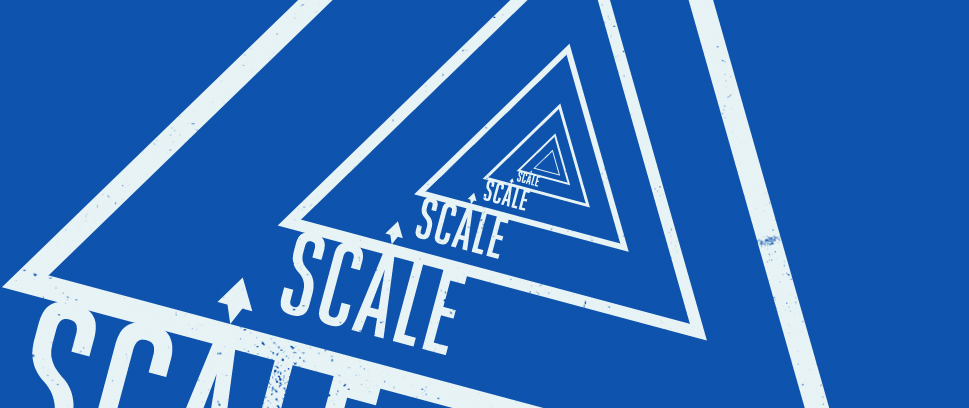

Scale is a puzzle game that allows players to scale objects up or down within the constraints of conservation of mass. If a puzzle’s solution requires walking through a hole in the wall and the hole is too small, for example, the player can increase the size of the entire wall in order to make the hole larger, but to do so the player first has to decrease the size of other objects in the game world.

I first saw a demonstration of Scale in the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco in 2012. I had my first chance to actually play Scale at GDC this year, and sat down with Swink for an interview shortly thereafter.

The Kickstarter campaign for Scale is running until Friday, November 15th. Scale has almost reached its goal for PC development, and an eventual release on Steam. The final stretch goal is to raise enough money to release Scale on Sony’s eighth generation PlayStation 4 console.

I enjoy seeing indie games made available on the widest number of platforms possible. The indie game movement advances game literacy in a way that blockbuster videogames, for the most part, cannot, and the further indie games can be moved out of the confines of their traditionally small, PC-based audience, the better.

What follows is an edited transcript of the conversation I had with Swink earlier this year. Scale has undoubtedly gone through several iterations since I last experienced it, but what I was most taken with was the spirit in which Scale was developed, which I am positive will shine through no matter how many iterations and changes the game goes through prior to release.

Unwinnable: What was your philosophy behind designing puzzles for Scale?

Unwinnable: What was your philosophy behind designing puzzles for Scale?

Steve Swink: The problem with designing puzzles is that they’re either infinitely difficult or infinitely easy. As soon as you’ve solved the puzzle it’s now zero challenge, but before you’ve solved it, all the time up until that point, is frustrating.

It’s really frustrating, as a designer, to watch somebody struggle with that, but at the same time that struggle is what’s beautiful about it. As a designer of a puzzle game, what you actually need to think about more than the puzzle and how clever it is in the moment when somebody solves it, which is what you often find yourself focusing on, is what they’re going to do while they’re trying to solve it, and how to make that really interesting.

Braid is perfect in that regard, because it plays with a series of steps over time, and you’re always going backwards and forwards and rewinding and it feels really good, and so it’s perfectly suited to making a puzzle game out of, whereas I think Scale is much more playful. It’s much cooler to just play around in a space and play with ideas of the size of things and be able to manipulate them and make fun or funny or interesting or weird or surprising things happen.

Unwinnable: Which do you think is more important in Scale? The play or the puzzle solving?

S. S.: I was talking to a friend of mine in New York about what I was doing with Scale and showing it, and she said “Why do you have to make puzzles out of it?” And I said, “That’s a really good question.”

I feel like a big failing of Shadow Physics [a previous puzzle game which Swink chose to stop development on] was constantly trying to find those really beautiful puzzles, and I found a few of them, but it was just like pulling teeth, and [when his friend made her comment] I was like, “That’s really smart.” So I have a bunch of ideas for puzzles, and ideas for stuff, but I think that what I’m going to do, moving forward, is just be way more open to what’s awesome about Scale.

I think sometimes you, as the designer, don’t get to decide how people are going to use the game or enjoy the game. I worked on Tony Hawk, and we had this idea that there would be like five different types of players who would play Tony Hawk. That was just written into the DNA of the company.

“Well, we need to have some stuff in the level for scoreheads, and we need to have some stuff in the level for people who collect everything, and we need to have some stuff in the level for actual skaters who just care about skating and they’re just going to skate the one bench over and over again, and they want to do videos and record stuff,” and so on.

That’s one of the exciting, interesting things about being a game designer: it’s a participatory medium. You can’t, you don’t get to decide how people are going to do stuff, so the best you can do is try to lead them into things that you think are really cool and fun. The space exists outside of you, in a weird way, and you’re just curating what happens in it.

Which is interesting, and letting go of that control is hard, especially for people like me who are control freaks. But then you have people who very successfully, almost scientifically, test levels over and over again until they can tell exactly what the player is going to be looking at, at any given moment, and they control that rigorously.

Unwinnable: You’re talking about Valve and the way they’re using biometrics and tracing eyelines and whatnot.

S. S.: Yeah, but I mean, you don’t need to trace eyelines to polish the shit out of Portal, right? You just watch a bunch of people play it and they test every week, and they watch people play it, and they find the parts where they get hung up and they fix those problems. And I think, actually, you can really disrupt the integrity of a work if you go overboard with that. I think rough edges and weirdness in games are really interesting.

The creator of Adventure Time, Pendleton Ward, was playing Scale and he was just laughing his ass off, and I was cringing because the stuff he was doing was, like, making a rock as big as the universe, and he was just blowing everything up and launching shit all over the place, and he’s just, “Oh my God, this is so awesome,” and I was like, “Okay, yeah, so, I need to stop controlling this stuff. I need to stop trying to control it quite so much.”

Unwinnable: You believe in revisiting older games to see what they have to teach you. Is there a particular older game which influenced Scale?

S. S.: I play old games all the time, and I think there are a lot of old games that do things well, and we’ve overlooked quite why that was and we’re taking way too many assumptions on faith.

Mario 64 has a lot to teach us about creating a playful space that is inviting and interesting, and for Scale, I’m looking at a structure that’s very similar to that. I want you to go in and play and be invited, but I want to give you some structure.

There’s a certain brilliance [in Mario 64], you come into a level and there’s like 20 different things you can do to get a star, but it gives you one in case you are feeling aimless. It’s such a simple, straightforward solution. We’ll just give you a list of things and you just do the top one on the list, and we don’t even show you the other ones. You unlock them as you go, so you don’t get overwhelmed or confused and there’s a certain, brilliant simplicity to that.

It’s so much better than whatever your latest objective is, it just pops up on your HUD, and you just do it.

Unwinnable: So it sounds like the spirit of play is more important to you than anything else.

S. S.: What I really want is people to experience something they’ve never experienced before, for people to feel a sense of wonder, which I hope will lead them to wanting to create their own stuff.

[Scale] is about the experience of something that you can’t experience in any other game, or in any other context, really, and it plays with the idea of the size of things, and the space between them. I don’t need to get wrapped up trying to make this a really difficult puzzle with a bunch of steps. It’s not very difficult, it’s just interesting.

Unwinnable: To what degree do you factor that potential distraction of fascination in Scale? Even if the puzzles are relatively simple, it is a puzzle game that ostensibly requires some concentration to solve.

S. S.: I think Jenova [Chen, designer of Flower and Journey among others] has a lot of really interesting ideas on this. How much structure can we take away and still have the player feel like they’re doing something interesting and meaningful and directed? That’s an interesting question, and I would like to pursue that.

Sometimes you have a thing that just invites people to be playful. I think Keita Takahashi does a wonderful job of designing games that just invite people to be playful. Katamari Damacy was a really interestingly perfect balance between a weird, crazy thing and being playful, and an actual structure for you to work in.

You can make a game that’s just a mechanic, like the scaling, and I can turn people loose with it and see what they want to do.

Unwinnable: Considering you wrote a book called Game Feel, what is the feeling or sensation you want to give players with Scale?

S. S.: At a basic, tactile level, when you are scaling an object up it’s almost like blowing up a balloon, like it has that same kind of playful thing, because blowing up a balloon is fun. It’s more fun if you’re using one of those little pump things so you don’t have to put the air forward, yourself.

It’s really important to me that scaling a thing feels really good, and so I put this little jiggle in it, when the inflation stops it kind of does this little happy jiggle thing. It’s subtle, and you don’t think too much about it, but it makes it more believable that any object could be changed like that, to me, for some reason.

I feel like a mechanic has to be free in some respects, otherwise why bother doing it, right? You play Mario, and there are levels in Mario that are about scaling stuff, like in Mario 64 there’s that level where you go through the tiny door, or the tiny pipe, and then you come out big and go back and forth, but to me those levels fall short of giving me the experience that I want which is the wonder of being able to really explore scale.

That’s how I arrived at the point of wanting to make this game. I want to play with the scale of objects, and I want to do it freely.

———

Follow Dennis Scimeca on Twitter @DennisScimeca. Learn more about Scale by following Steve Swink on Twitter @SteveSwink, or check out the Kickstarter campaign.