Decision 2000

I have a confession to make. I voted for George W. Bush. But not in 2004 – when the tragic, unnecessary debacle of the war in Iraq was still ratcheting up in scope and bloodshed. This was 2000, the year I turned 18.

It’s not that I look back on that decision with regret. I really just didn’t know any better. Having been raised in a Christian household, my understanding of presidential politics boiled down to one all-important moral issue. Either you cast your ballot for the God-fearing Republican or you condoned the killing of babies. It was really that simple.

[pullquote]Isn’t that how monopolistic power works in secret – by playing both sides against one another while benefiting from either outcome?[/pullquote]

On the night of November 6, one day before the election, I was at a Pearl Jam concert in Seattle. I remember one particular banter break during which Eddie Vedder did a quick crowd poll to see who would be voting for whom. In this particular demographic, it was Green Party candidate Ralph Nader who registered the loudest applause, with Gore probably a close second. I was a little taken aback. Could it be there were more than two angles from which to view this political theater?

Needless to say, I didn’t exactly project my enthusiasm when Vedder called out for the Bush voters. I offered a few cautious claps but otherwise kept my head down. Even then I wasn’t particularly passionate about my decision. It was never really mine to begin with.

———

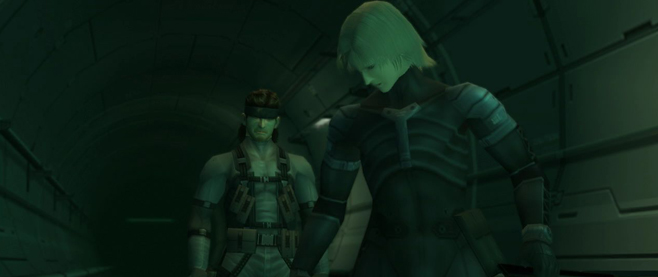

It was only a little earlier that year when I found myself at an altogether different sort of crossroads. I was coming upon the end of the game Deus Ex, and my player character JC Denton was deep inside Area 51.

For the past few days I had been on an ever-expanding mission, pursuing the threads of a global conspiracy from New York to Hong Kong, from Hong Kong to Paris and ultimately to here – the ground-zero of conspiracy theories. Already I had uncovered a plot to decimate the human population by way of a manufactured virus. I’d brushed shoulders with members of the Illuminati, infiltrated a Knights Templar compound and played at some laser-sword swashbuckling with the men (and women) in black. But this final turn of events was just as unexpected as the others.

As it turned out, Area 51 was more than a site for storing and researching extraterrestrial technology. It was a fiber optics hub for electronic communications, and my final objective was to prevent Bob Page, the world’s richest man, from merging with an A.I. supercomputer that would transform him into a virtual – and tyrannical – god among men.

But it wasn’t that simple. There were three separate parties telling me how I should put the kibosh on Page’s usurpation. One person, my Illuminati buddy, said I should kill Page and join his secret fraternity. Together we would guide humanity to a better future as the Illuminati had always done, from behind the scenes.

The A.I. construct was telling me that I – not Page – should be the one to do the merging, that with its infinite access to real-time information coupled with my human conscience we would be able to rule the planet as a benevolent dictator. Governing power would be ceded to an all-knowing and compassionate machine.

The A.I. construct was telling me that I – not Page – should be the one to do the merging, that with its infinite access to real-time information coupled with my human conscience we would be able to rule the planet as a benevolent dictator. Governing power would be ceded to an all-knowing and compassionate machine.

My third and final option was to destroy Area 51, thus crippling the global network altogether. It was essentially an act of desperate anarchy, committed in the hope and belief that mankind would be freed from the shackles of global despotism. It would be like hitting the reset button on the information age. Communities would rebuild through localized governance and self-sufficiency. At least that was the idea.

I had genuinely liked my elitist friend up to that point, but his motives seemed suddenly duplicitous – hardly more honorable than Page’s. Why should I trust him?

Had the A.I. construct not been voice acted so creepily, who knows? Maybe I would have been more persuaded by its trans-humanist argument. But this was still a few years prior to the emergence of social networks and big data, technologies that have already brought us closer to the theoretical hive-mind. It was still a bit too radical for me to wrap my head around.

Of course I ended up trying out all three options, but it was the “dark age” ending I attempted first and the only one of the three choices that felt true to my conscience.

———

It took a while for me to start building my political identity. Even through college, I had a hard time making sense of the conservative/liberal spectrum.

My freshman year I heard Ralph Nader speak at my campus. He talked at length about the lack of core distinction between the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as how the media tended to perpetuate the narrow boundaries of acceptable political discourse. It was a compelling argument, and as it turns out I voted for him in 2004 (and again in 2008).

In 2006 I began – on a whim, really – to explore where money came from. I started reading about the Federal Reserve System and how it was conceived on Jekyll Island by a handful of elite, mostly New York bankers. I was floored to discover how our currency was created out of thin air through the magic of fiat currency, then further multiplied through fractional reserve banking.

It’s difficult to describe what this new information did to my psyche. I felt significantly more informed, but also a bit paranoid about the stability of our social order. A hyperinflation disaster seemed like something that was most likely going to occur in my lifetime. I wanted to abolish the Fed, to return the power of financial sovereignty to the people.

It wasn’t so different from the world of Deus Ex.

The series has always been surprisingly chatty when it comes to geopolitics. For a videogame based largely around first-person shooting, it amazes me the kinds of discussions my character strikes up with NPCs – be they bartenders, bureaucrats, gangsters or bums.

While some dialogue exchanges come off a bit silly, given the context, the games do have some thought-provoking episodes. There’s a moment in the 2003 sequel, Invisible War, when protagonist Alex D. stumbles upon proof that two rival coffee chains are owned by the same parent company, a fact unbeknownst even to the local store managers. By catering to different customer tastes, the ensuing public rivalry was intended to strengthen brand loyalty for both chains. It was a perfect foreshadowing for a much larger revelation later in the game.

I saw it as no small epiphany. Isn’t that how monopolistic power works in secret – by playing both sides against one another while benefiting from either outcome? Wasn’t it a fitting microcosm of corporate incest, whereby a handful of media conglomerates controls almost everything we see and consume? Wasn’t it also similar to how a two-party political system could create the illusion of choice and competition – and real division among its citizens – while remaining unified in their collectivist ideologies and general servitude to the powers that be (central banking systems, the military-industrial complex, etc.)?

———

I think I need to make another confession. For the past seven years I’ve been somewhat of a 9/11 skeptic, and by that I mean someone who isn’t sure that the “official” explanations for the terrorist attacks are entirely accurate. I don’t claim to have any solid answers. I don’t align myself with any particular theorists or theory peddlers out there. All I’m saying is I don’t know what really happened, and I can’t rule out that there may have been elements of our government that were either complicit or outright involved.

I think I need to make another confession. For the past seven years I’ve been somewhat of a 9/11 skeptic, and by that I mean someone who isn’t sure that the “official” explanations for the terrorist attacks are entirely accurate. I don’t claim to have any solid answers. I don’t align myself with any particular theorists or theory peddlers out there. All I’m saying is I don’t know what really happened, and I can’t rule out that there may have been elements of our government that were either complicit or outright involved.

Was it a plane that hit the Pentagon? Maybe, although I haven’t seen the visual evidence that has really settled my doubt once and for all. Was it fire and flying debris that brought down World Trade Center 7? Believe me when I say I want to believe that’s the case, because it’s damn hard to imagine either how or why a controlled demolition would have been carried out amidst such chaos.

My point isn’t to argue about 9/11 truth, and I don’t care if people think I’m an idiot (or worse) for holding onto the reservations that I have. I’m just being honest.

Like many other skeptics, I never felt a need to question 9/11 until almost five years after the fact. That’s about when YouTube started popping up with all kinds of videos and documentaries on the subject, including the infamous Loose Change.

As I began weighing all the information being presented to me, I had a parallel flashback of my time with Deus Ex, a game set in a dystopian future beset by acts of terrorism.

There’s a moment when you come to realize that your brother Paul Denton has been converted to the side of the secessionist organization that both of you – as agents of the United Nations Anti-Terrorism Coalition – have been fighting against.

Up to that point, I had given no consideration to the possibility that my orders and intel had been some kind of red herring, a cover to a more complex and sinister plot line. I never bothered to really question the “terrorist” label that was being used to justify the authority of lethal force I was employing against my adversaries. Before long, I too was running headlong from the same jack-booted thugs I used to work for.

I’m a lot less fervent in my conspiracy chasing these days. There are too many rabbit holes, and endless speculation rarely leads to enlightenment – probably the opposite. But when I take a quick inventory of stories in the news media, I still see the troubling tendencies of a creeping police state, backed up by a domestic and international spying network.

Despite some eerie coincidences, Deus Ex did not predict 9/11. It did, however, plant a seed in my mind that government institutions, however sheeplike in their outer appearance, could be vicious wolves underneath.

It’s hard not to see some truth in that.

———

At the time of its release, Deus Ex felt like a game of unmitigated freedom. It welcomed so many different play styles. It offered open-ended solutions to its objectives.

Of course – being the narrative-driven game it is – that freedom did have its parameters, particularly as the game funneled players toward its inevitable scripted conclusion(s).

Contrary to Owen R. Smith’s retrospective criticism, I think the significance of the Deus Ex endings has less to do with what the game is saying and a lot more to do with what the player’s choice says about the player. Even today you can watch a YouTube video of the three endings, then read user comments discussing which option is the most morally and philosophically desirable. It’s refreshingly civil.

As I grow older, I find myself caught up in these repeating cycles of political disillusionment. I feel myself slowly reverting to the apathy of my early adulthood, and I want nothing to do with these mud-flinging, choreographed elections.

As I grow older, I find myself caught up in these repeating cycles of political disillusionment. I feel myself slowly reverting to the apathy of my early adulthood, and I want nothing to do with these mud-flinging, choreographed elections.

I’ll be the first to admit there’s a sense of retreat in voting third-party. Yes, it’s a vote of conscience, but there’s more to it. I feel justified for having participated in the democratic process without ever having to feel like I bear responsibility for the failings and atrocities committed by the winning party. I might never have to see my ideologies actually tested and played out in a real-world scenario – forced to witness whether my most treasured political values soar or plummet.

Maybe that’s also why I like playing videogames. They hand me a similar carte blanche. I’m free to role-play from any moral vantage, to experiment with any ideology I choose. There’s no risk in being wrong.

If someone were to ask me to name my favorite game, I would probably still pick Deus Ex, at least for now.

If asked about my political affiliation… I don’t know. I might say I lean Libertarian, but even that label comes with so much baggage these days. If I had the time, I’d try to espouse the virtues of individual rights, equality under law and freedom of choice.

Is it strange I associate those things with Deus Ex?

———

Flynn writes in much shorter sentences on Twitter @brinywater.