The Great and Secret Gaming Photographer

I’m a very accomplished photographer. My photos have been in magazines, newspapers, textbooks, blogs, online videos, television and any other medium that you can think of. My work has been seen by millions and will be one of the most important resources for the history of videogames. The only catch is that I’m almost never credited and don’t get paid for it.

Wikipedia is one of the Internet’s most powerful sites, with its massive user base and high-ranking results in search engines. As a result, the photos associated with its articles quickly become some of the most-seen images on the Internet. This massive visibility, however, comes at a cost: to place a photo on Wikipedia a photographer must give away all rights to the photo for free. This leads to massive exposure for your work, but at a price: you must release your rights so your photos can be used by anyone, for any purpose, without any compensation.

It’s a crazy tradeoff for a professional photographer, but this is exactly what I do, because my passion for videogames and photography outweighs any potential financial gain. I take high-quality, hi-res photos of videogame hardware and upload them to Wikipedia. From there, these photos spread – showing up in videos, magazines, blogs and news articles.

It’s a crazy tradeoff for a professional photographer, but this is exactly what I do, because my passion for videogames and photography outweighs any potential financial gain. I take high-quality, hi-res photos of videogame hardware and upload them to Wikipedia. From there, these photos spread – showing up in videos, magazines, blogs and news articles.

I didn’t realize this would happen when I first started taking pictures of game consoles. It all began because I was annoyed by low-quality pictures on Wikipedia: small, poorly composed and lacking consistency. When I looked further, I found it was the same situation across the rest of the Internet. Why had no one bothered to take good pictures? If no one else was going to, I would do it.

I made the jump from Wikipedia reader to Wikipedia contributor. Many don’t survive the experience: the rules and bureaucracy of Wikipedia’s formatting, along with the surprisingly unfriendly atmosphere new editors face, makes the learning curve steep. I made beginners’ mistakes and took hits for them, but my work started becoming more proficient and my persistence paid off: my photos began transforming Wikipedia articles.

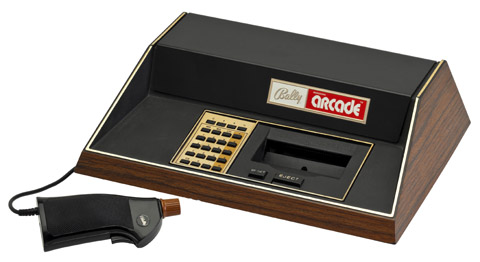

At first I took photos of food items, candy bars and electronics, but then I began narrowing my focus onto videogame systems. I started making lists of every console ever released. Before the videogame crash of 1983, there were numerous systems, many now barely remembered, with little information available. Message boards and fan sites had vague details, with the same poor, low-resolution pictures. I realized that relatively recent history was being lost to time, all because the Internet did not have good information about these game systems. There was a need to document these systems and show people what they looked like before they’re forgotten to time.

At first I took photos of food items, candy bars and electronics, but then I began narrowing my focus onto videogame systems. I started making lists of every console ever released. Before the videogame crash of 1983, there were numerous systems, many now barely remembered, with little information available. Message boards and fan sites had vague details, with the same poor, low-resolution pictures. I realized that relatively recent history was being lost to time, all because the Internet did not have good information about these game systems. There was a need to document these systems and show people what they looked like before they’re forgotten to time.

The problem is access to the actual systems. I only had a small collection of consoles to photograph, and it’s the same stuff everyone else owns: an NES, an Xbox and so on. But who the hell owns a VTech CreatiVision? Who has even heard of a Bally Astrocade?

I started contacting collectors and anyone willing to help. I found a passionate collector on Long Island, so I lugged all my photo equipment and lights on the Long Island Rail Road to his house to get the pictures I needed. After just a few hours of intense work I was able to more than double my previous collection of photos that I had taken over weeks. I found an independent games store, Video Games New York, that let me “rent” out the hardware they sold, as taking pictures in the store would have been impossible. There was also James Baker, an enthusiast whose collection covered a large wall at his business. With the assistance of just a handful of collectors I was able to document a large amount of videogaming history, with a gallery that including rare consoles like the Sega SG-1000 and the Casio Loopy.

Despite my progress there were still gaps, with systems and hardware too numerous and obscure to be covered by local collectors. Travel to other collectors was cost-prohibitive – remember, I’m doing this for free. It wasn’t in my budget to purchase newer systems that needed photographs like the Nintendo 3DS, the PlayStation Vita and Wii U. (Plus, who wants to own a Wii U right now?) And as my process improved, I wished I had the opportunity to redo some of my earlier work. Facing these challenges, my work halted.

Despite my progress there were still gaps, with systems and hardware too numerous and obscure to be covered by local collectors. Travel to other collectors was cost-prohibitive – remember, I’m doing this for free. It wasn’t in my budget to purchase newer systems that needed photographs like the Nintendo 3DS, the PlayStation Vita and Wii U. (Plus, who wants to own a Wii U right now?) And as my process improved, I wished I had the opportunity to redo some of my earlier work. Facing these challenges, my work halted.

It was during this lull that my pictures starting taking off. Gaming blogs and YouTube series about gaming began using my photos, especially the older consoles. Newspapers and magazines were using them as well. This took me by surprise, but the reasons were obvious: because my photos on Wikipedia are immediately available and usually what a person finds first when they Google the subject. Also, the photos are easy to reproduce – they’re direct and clear photos with white backgrounds – and they’re free, so there’s no need to find original owners and get permission (if they can even be tracked down). As a result, my photos were popular and being used around the world.

However, even if my photos were being used often in numerous places, it was usually without credit. Maybe it’s because the pictures are free, or maybe it’s because of the nature of the Internet. Either way, I’ve come to terms with it; I’m just happy that the work is being seen and used.

Even without accreditation, people found me on my Wikimedia page. I would get the occasional thanks for my photos, like the one of the Vectrex system (an obscure flop). I began to realize this was less about the quality of my work and more about saving and sharing the history of gaming. It turns out that my videogame gallery is a valuable resource of gaming information: one central location, easily found through a web search, with consistent and complementary high-quality images available to all for free.

I wanted to continue and expand my work with new ideas: more pictures from different angles, motherboard shots, videos and detailed descriptions. Yet the same problems remained: access to systems and money. But I now understood that there was a community of gaming fans that appreciated this work and could help close the gaps. I started a Kickstarter to appeal to the gaming community and ask for their help in transforming my current gallery of pictures into an expanded and in-depth site tailored to gaming history’s needs. The funding would allow me to purchase old and obscure systems and spend the time to document them in the detail they deserve.

I wanted to continue and expand my work with new ideas: more pictures from different angles, motherboard shots, videos and detailed descriptions. Yet the same problems remained: access to systems and money. But I now understood that there was a community of gaming fans that appreciated this work and could help close the gaps. I started a Kickstarter to appeal to the gaming community and ask for their help in transforming my current gallery of pictures into an expanded and in-depth site tailored to gaming history’s needs. The funding would allow me to purchase old and obscure systems and spend the time to document them in the detail they deserve.

There is a huge need for this. There is no one else trying to provide this service at this level, at this quality, at this reach (Wikipedia) and in a format (public domain) that will ensure that these photos will last for decades from now. The work that I’ve already created and its impact thus far is a testament to the importance of the project. These are the reasons why I do this work, and why I do it for free.