Sex and Psychosis

It is not uncommon for notable artists to cultivate signature styles. Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Keith Haring are instantly recognizable, and even some game developers have established an unmistakable style in their games.

Team Ico is one example that comes to mind. Similarly, Goichi Suda – or Suda51 as he’s often known – is a high-profile developer who is seen as an auteur in the games industry. But while his artistic vision is overwhelmingly evident in the works his team produces, elements of this vision have a tendency to muddle what would otherwise become a refined, unique and compelling artistic signature.

Put simply, Suda51 is at his best when he leaves his adolescence behind.

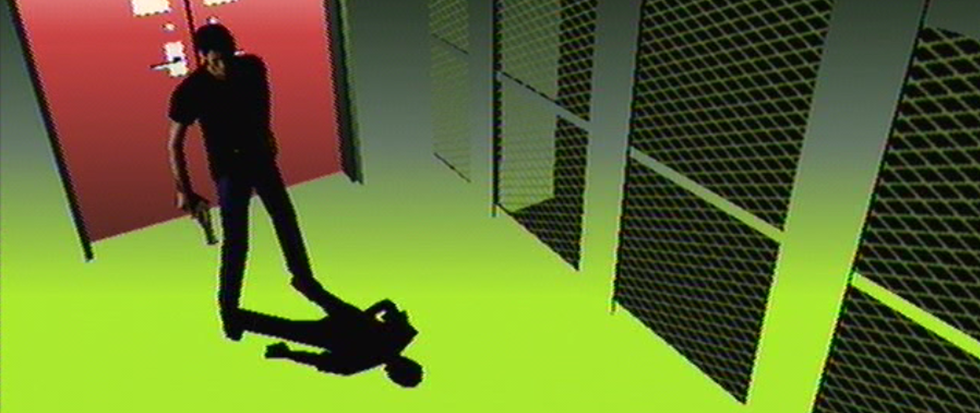

Suda’s early defining work – and arguably his best – is Killer 7. The initially Gamecube exclusive, part of the somewhat defunct “Capcom five” that also included Viewtiful Joe and Resident Evil 4, brought Suda worldwide notoriety and introduced gamers and critics to a mind with an obvious depth of creativity that stood distantly apart from the crowd. Why? Killer 7 introduced themes of sex and psychosis amid science fiction, interesting and original expressions or violence notwithstanding. While sex would factor heavily into Suda’s later works, here it was seamlessly incorporated into a narrative and accompanying aesthetic style in a way that served a purpose, and was in no way gratuitous.

Further, like more traditional forms of art, Killer 7 left something to audience interpretation. This quality served it well, despite a handful of unfavorable reviews easily attributable to critics unprepared for the medium to evolve intellectually. (Stuff, Maxim – I think you get the idea.)

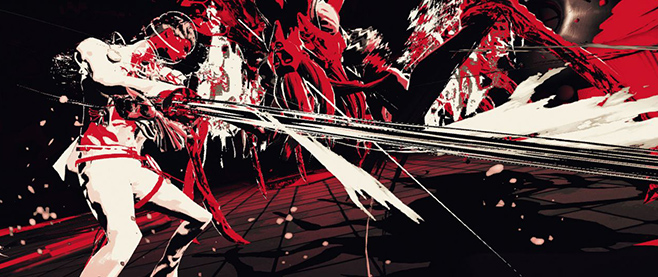

Fast-forwarding eight years to what many hoped would be a worthy successor to his inaugural North American work Suda has given us Killer is Dead, a game whose aesthetic aspirations hark back to Killer 7 as much as its title. Killer is Dead has already been plagued by vestiges of its creator’s intermediate offerings. Its narrative is deranged, though less complex and engaging than its predecessors, and the game’s mechanics stand both to complement the plot and to satisfy gamers’ needs for responsive and rewarding combat systems. So it gives a strong foundation for theoretical acclaim. But the teenager inside Suda showed up, too.

Adolescent threads have found their way into Suda’s games since his initial incarnation as Travis Touchdown in No More Heroes, a game whose teenage fantasy revolves around an Otaku-loving, porn-and-wrestling obsessed loser who decides to become an assassin for hire. (No More Heroes was Suda’s first game localized after Killer 7.)

Despite being a 27-year-old assassin, Travis is a perpetually adolescent character down to his manner (uncouth) and his behavior (sociopathic), especially with regard to women. For Travis, women are mythical creatures that somehow remain entirely alien and incomprehensible to him throughout the game’s twisted narrative – it’s clear that he is simply unable to incorporate an appropriate understanding of women into anything resembling a socially well-adjusted existence. Any confidence Travis may possess in either game only comes from his ability to fight or from his Otaku-level expertise in topics surrounding his hobbies. In all other situations, his grandiose self-image deflates into self-consciousness and uncertainty.

As standalone character studies, No More Heroes and its sequels may work ironically, despite such a distasteful antihero serving as their protagonist. However, Travis Touchdown’s attitude has factored into the development of later games in Suda’s catalogue, almost entirely to their detriment.

Killer is Dead has been panned by critics for its Gigolo Missions, which consist of ogling sexy women long enough to build up the “guts” to present them with gifts until they go home with the leading man, Mondo Zappa. Without firing off accusations of sexism and mysogyny – there are plenty of those already – it’s safe to say that these segments are entirely irrelevant to the rest of the game’s content, and force players to disengage from its fairly captivating central narrative. There are only a handful of these optional missions, but still, how did Travis Touchdown manage to escape his No More Heroes confines and non-ironically compromise the integrity of an otherwise unified and focused work?

Wherever Suda’s agent of adolescence appears, the quality of the experience suffers. Lollipop Chainsaw was not written by Suda, but was dominated by the Travis Touchdown perspective under Suda’s guidance (thanks to a script from Troma-famous James Gunn). Lollipop Chainsaw is entertainment prepared by a third party for Travis to enjoy: a scantily clad high-school cheerleader, teeny-bopping her way through hordes of zombies and flashing her panties as often as possible. The uniqueness of Suda’s signature style, as presented in Killer 7 and attempted again in Killer is Dead, is entirely absent, replaced by the plainness of Travis Touchdown’s hormonal impulses.

This immature exhibition fails to provide the audience with anything but the ordinary thoughts and images that run through the minds of every preteen boy on a daily basis; we can find them everywhere. Suda has long since shown us worlds and concepts unattainable from anywhere other than his own mind. This creative rarity is what’s truly valuable to his potential audience.

In a sense, every Suda game has become a balancing act. One side of the scales carries the Suda who gave us Killer 7. This is the true, serious artist, the Salvador Dali of game designers; the one we need to pay attention to, who will ignite something new for us as gamers. The other side carries the heavy weight of Travis Touchdown, desperately struggling and squirming his way out from inside of Suda to wisecrack and ejaculate all over everything with which he comes into contact. Finally, game mechanics either salve or exacerbate the Touchdown-transmitted infection, giving hope to titles like Killer is Dead until the next Killer 7 arrives.

Shadows of the Damned, a grindhouse-styled road movie of a horror game that Suda enlisted the help of Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami to finish (a game that was published by EA, of all companies), created a greater symbiosis from the duality of Suda’s psychosis and Travis’s sexuality, arguably more than any game he’s made. Sex in Shadows of the Damned is overt and gratuitous, and even hard-ass hero Garcia Hotspur isn’t completely immune to his inner Travis.

Here, however, sexual imagery and suggestion are warped and diabolically sensible in the context of a journey into the depths of hell. The game’s sexual content is also subversive in that sex is never there just to be cool, and never holds any power over the protagonist or the player. Sex isn’t a distraction, but an integral part of the madness Garcia experiences on his single-minded quest.

Garcia even said it himself: “Bitch, I’m not falling for that sexy bullshit.”

Perhaps Suda should take that statement to heart.

———

Follow Eddie Inzauto’s Sudaish ramblings on Twitter @EddieInzauto.