Second Banana

By their very nature, sidekicks are second-rate.

But holy under-appreciation, Batman, they at least deserve the same full share of respect as their higher-profile partners for their place in the pop culture pantheon.

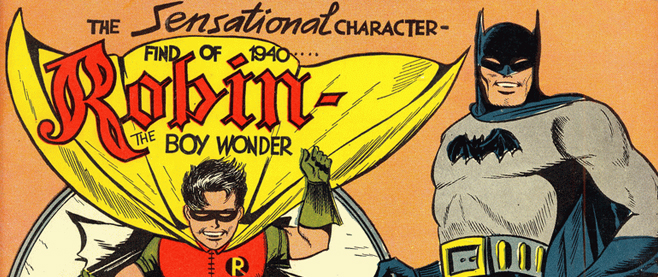

Rather than true partners, though, they have been doomed over the years to either be comic relief, a point-of-view character among younger readers or a bland counterpoint to the hero of the story. Dr. Watson, for example, seems positively elementary compared to the great deductive mind of Sherlock Holmes in Arthur Conan Doyle’s beloved books, a convenient measuring stick to show readers just how smart his eccentric partner is. Bob Kane or Bill Finger (or perhaps Jerry Robinson) added Robin after Batman’s debut in Detective Comics #27, to make the Caped Crusader a little less foreboding to the boys buying the comics.

“That was the theory – it always seemed strange to us who read the comics at the time, because which one did you want to be, Batman or Robin?” asks comic book legend Roy Thomas. “They didn’t identify with Robin, they wanted to be Batman.”

Sidekicks may have needed to be rescued more times than not, but they also bailed out their bosses, in a manner of speaking.

“When Joe Simon presented his pitch to [then Timely Comics publisher Martin Goodman] for Captain America he said, ‘I think he should have a teen sidekick because otherwise Cap will be talking to himself all the time.’ It stopped the character from having to either have a lot of thought balloons or have endless exposition.”

In the end, Bucky couldn’t be rescued from his most diabolical enemy – Stan Lee.

“Stan hated the idea of kid sidekicks,” says Thomas, who himself knocked off the original Human Torch’s pal Toro. “When we brought back Captain America, he immediately killed off Bucky in the storyline.”

Even death, though, couldn’t keep Bucky from his last noble assist to his mentor: the storyline provided Captain America with the emotional baggage that would be mined for decades by writers.

In the same era on television, there were a batch of sidekicks dispensing justice that were even more awkward than teens.

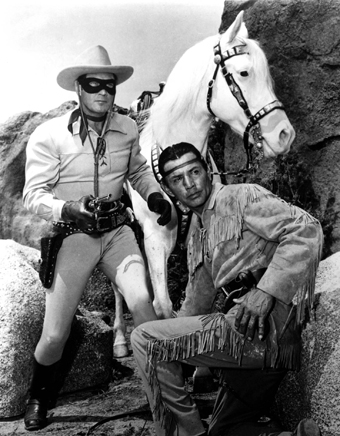

The Lone Ranger’s Tonto, played by Jay Silverheels, and The Green Hornet’s Kato, played by a young Bruce Lee, were stereotypes that are cringe-worthy by today’s standards.

“My earliest memories of The Lone Ranger, I was probably five or six years old in Kentucky, it was very famous – you’d hear the William Tell Overture and it would sort of burst through your screen in black and white,” Johnny Depp told this reporter this summer.

“My earliest memories of The Lone Ranger, I was probably five or six years old in Kentucky, it was very famous – you’d hear the William Tell Overture and it would sort of burst through your screen in black and white,” Johnny Depp told this reporter this summer.

“I loved the show, but there was always something I was slightly perturbed about, even then: why is Tonto considered the sidekick? That didn’t sit well with me, the idea that the Indian was put in the position to be the kind of fetching boy or something,” added Depp on his motivation to rewrite that history in playing the part in The Lone Ranger movie.

At least there was an Indian actually fetching some time on mainstream television back then – during an era when there was a lot more white than black on the screen.

“They were roles for people who generally had no roles in media available for them,” says Prof. Robert Thompson, Director of the Bleier Center for Television & Popular Culture at Syracuse University. “This gets very dicey, because one could make the same argument of Amos and Andy, which in retrospect is considered the gold standard of offensive stereotypes.”

Thompson points to Valerie Harper’s Rhoda, of all sidekicks, as one of greatest examples of all time. The best friend of the WASPy Mary Richards on The Mary Tyler Moore Show was Jewish – and proud of it.

“The fact that Rhoda was Jewish was very unusual in 1970,” he says. “We had a lot of people who were Jewish who started television, but they very seldom play Jews. And Rhoda, who was outspokenly Jewish, that was the way sidekicks could slip, Trojan horse-style, in some diversity.”

That phenomenon was taking place in the pages of the comic books as well, where Captain America had picked up a new partner – the African-American Falcon, created by Lee and artist Gene Colan in 1969. The new superhero gave Captain America – not to mention Marvel – some badly-needed street cred at the height of the civil rights movement.

As the industry shifted towards older readers with more mature stories, sidekicks also officially grew. Writer Dennis O’Neill and artist Neal Adams’ now famous anti-drug storyline on Green Lantern/Green Arrow featured Speedy, Green Arrow’s trusty sidekick, shooting up heroin. It’s as shocking now as it was in 1971.

As the industry shifted towards older readers with more mature stories, sidekicks also officially grew. Writer Dennis O’Neill and artist Neal Adams’ now famous anti-drug storyline on Green Lantern/Green Arrow featured Speedy, Green Arrow’s trusty sidekick, shooting up heroin. It’s as shocking now as it was in 1971.

Dick Grayson, the original Robin, became Nightwing in the Eighties, trading his bright red shirt and green shorts for a darker, edgier blue costume. He’s positively milquetoast, however, compared to Alan Moore’s Kid Miracleman, who became one of the most sadistic villains in comic history after developing a psychotic hatred of his former mentor.

Comic book fans were ready to storm Marvel’s offices when Bucky was brought back from the great beyond by retconning him into the KGB-brainwashed killer known as The Winter Soldier by writer Ed Brubaker in 2004. Within a few years, however, the character became so popular that he took over the mantle of Captain America when Steve Rogers was believed to be dead.

When the real Captain America returned for his big red boots, fanboys were split on who deserved the shield.

“I always think those are the same 50% that were really angry I brought Bucky back, and then they were the ones that were really furious that Bucky became Captain America and now they’re like how dare you not leave Bucky in the costume,” Brubaker told Unwinnable in 2011.

At long last, finally, sidekicks are no one’s second bananas.