Building Babycastles

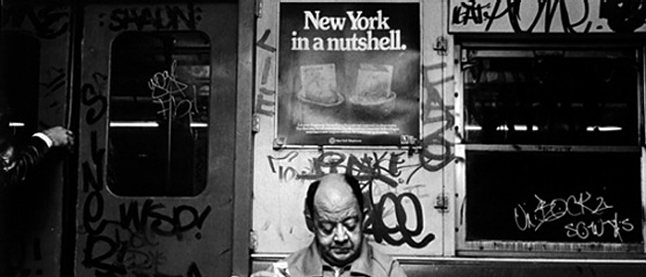

On the top floor of a landmark building in downtown Manhattan, three arcade cabinets stood against a wall in Duke Reuben’s Pizza Kingdom. The beige linoleum floors had been installed temporarily. Music from the ’90s blasted. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene had posted a grade of “C” in a window near a sign that read “Be Patient, Meatball!”

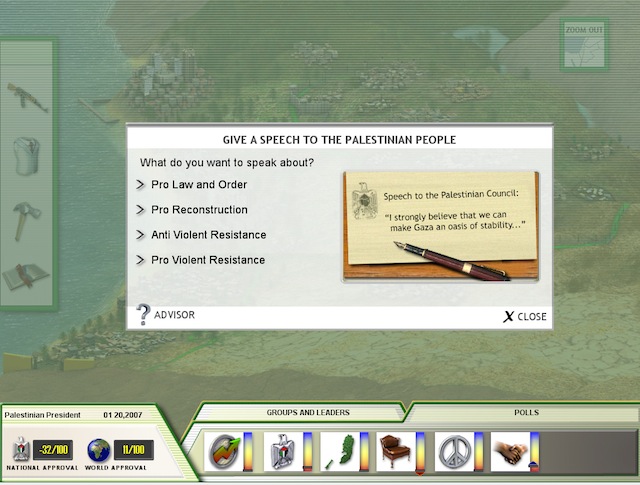

Everything about the room, including the cardboard decorations and marquees on top of the arcade games, had an air of scruffiness. Visitors played videogames in wooden cabinets. These weren’t typical arcade games. There was no sign of pinball machines or Galaga. The games on display – PeaceMaker, Harpooned: Japanese Cetacean Research Simulator and I Was in the War – were the creations of independent video game developers.

To the uninitiated, this may have seemed like a working pizzeria and a unique arcade. In reality, it was an exhibition of independent video games put together by Babycastles, a New York-based group that exists to promote video games built by independent developers without a lot of money and the backing of large publishers.

The fictional pizzeria was the backdrop for Babycastles’ December 2012 project “Babyharvester, ” named for a portmanteau of Babycastles itself and collaborator Slice Harvester, a pizza review fanzine. The exhibition was held in the Clocktower Gallery, an alternative art studio on the 13th floor of a government-owned landmark building in Tribeca that is also home to a criminal court.

Babycastles’ aim is to show off independent games as a form of social culture to the masses. If it succeeds, it will have people talking about games all the time, not just during an exhibition (and not just about the games you would find at your local GameStop). Ideally, conversation would also revolve around little known games produced by small independent developers that most people have never heard of.

What drives Babycastles’ membership is a love of promoting unique games that they think can get people talking. They want people to be exposed to them in the same way people are exposed to more prominent forms of art – to talk about them like they would talk about books or movies.

“You’d name games in the same breath as you’d mention [film, music, dance, literature, journalism, architecture, art and fashion] and it feels natural,” says Frank Lantz, chair of the Game Center at New York University. “Maybe it didn’t ten years ago. But now it does.”

The December exhibition marked a turning point. In earlier, less turbulent days, the group had a permanent venue in the basement in Ridgewood, a borough of Queens. The Clocktower Gallery was one of the venues Babycastles had ended up in temporarily. The end of Babyharvester meant Duke Reuben’s had to be torn down, the cabinets put away.

For now Babycastles still hopes to find a more permanent space – it is still trying to figure out where that home may be while striving to become a more formalized, credible organization. If Babycastles’ ambitious – and somewhat lofty – plans for the future take root, though, the collective won’t jus be a little-known group of indie gaming enthusiasts, but a wider resource for independent developers with an infrastructure to help them thrive.

———

Kunal Gupta and Syed Salahuddin, the co-founders and principal operators of Babycastles, meet weekly over bowls of pho to chat and talk about the group and its goals. Salahuddin and Gupta – like everyone else involved in the organization – have day jobs. Gupta helps run an art collective and music venue in Bushwick, is in a band called Loud Objects (they make music out of digital circuits) and also works as a freelance programmer.

“[That’s] when I’m poor,” Gupta says, laughing. “Which is always.”

Salahuddin is an adjunct professor of computer science at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. He teaches an introductory programming course, a game development studio class at NYU’s Polytechnic Institute and an electronics course called “Short Circuit” for a middle school in Chelsea. Another freelance programmer, Salahuddin also helps to run a housing cooperative in Clinton Hill.

The two met in 2008 as graduates in the Interactive Telecommunications Program at New York University. Rather than the actual coursework, though, the friends soon found themselves more interested in discussing the culture of games, especially indie games no one else had heard of. Gupta had discovered his passion for independent games when he was an undergrad at Columbia – he loved making his own projects and curating them in his free time. Salahuddin was meanwhile introduced to TIGSource, an online community of indie game developers.

“It was a really exciting time for independent games,” Salahuddin says.

Both Gupta and Salahuddin were interested in weird moments you couldn’t find in a lot of more mainstream games at the time – although Gupta recalled that Metal Gear Solid’s boss battle against Psycho Mantis, a psychic villain that developer Hideo Kojima used to break the fourth wall back in 1998 – was indicative of the type of game experiences they were interested in.

“People would refer to Metal Gear Solid, pulling the controller out for the [Psycho] Mantis,” Gupta says, referring to the player having to actually switch controller ports on the PlayStation in order to avoid Mantis’ mindreading abilities. “Interesting moments in games, but they’re such a tiny subset of all of the expression [in videogames].”

Another interest Gupta and Salahuddin shared was putting up arcade cabinets in venues whenever and wherever they could. Gupta put a copy of the indie quasi-Space Jam parody-sequel Barkley, Shut Up and Jam Gaiden in the office of a record label in Brooklyn that was run by a friend, for one. Then a friend encouraged them to put up a permanent arcade in the basement of his space in Queens. The burgeoning Babycastles –whose moniker comes from a Japanese pastry that loosely translates to the phrase “Baby castles” – gradually grew. Members gathered weekly to discuss video games, plan exhibitions and prepare to build and curate exhibits so that others could experience notable indie games.

“Babycastles became that moment where we turned those pop-up [cabinet exhibitions] into a permanent space,” Gupta says.

After a robbery in 2011, the space Babycastles had been occupying in Queens closed.

Finding a new, more permanent venue to set up shop and hold exhibitions hasn’t been easy.

“That’s a New York arts infrastructure problem,” Gupta says. “It’s hard to carve out a space for art that lasts longer than one day.” Gallery models – one of the more popular methods for up-and-coming artists to showcase their work in a semi-permanent space – only works if you have something to sell; working on more underground projects (“punk art,” as the duo call it) makes it much harder to find accommodating outfits.

For their Babyharvester show at the Clocktower Gallery, Gupta and Salahuddin were able to keep track of the various aspects of putting together a Babycastles project: curation, logistics, hardware, software, arcade cabinets and accounting. The goal is a template that anyone with an interest in running their own shows can follow.

“Curation is a fun one, because anyone can do it,” Gupta says. “The less experience you have, the more interesting it is – though there have been some superstar game curators as well.”

Anyone at Babycastles can curate games for an event. A curator’s day-to-day involves researching games to showcase – usually involving some sort of theme – then picking the games that end up in an exhibition.

Take Babyharvester’s display games – PeaceMaker, Harpooned and I Was in the War – all games that bring conflict or hostility to the comforting haven of a pizza parlor arcade.

Rather than being allowing an escape from the violence that proliferates daily news, PeaceMaker puts you in the shoes of either an Israeli or Palestinian leader attempting to make peace. Harpooned foists command of Japanese whaling ship. I Was in the War involves moving across the screen to dodge soldiers, tanks, missiles and nuclear warheads.

Curators also reach out to developers, handle financial matters (like artists’ fees) and generally keep up communication among involved parties, press and promotional like show photography notwithstanding.

But before all that you need hardware. Babycastles gets around this by collecting donated parts and decade-plus old computers from members’ friends and families – machines that can still handle most indie-titles that aren’t too graphically-intensive. Then it’s a matter of getting games to showcase.

Unlike big-budget counterparts, indies don’t usually go through an extensive testing process to get rid of bugs, meaning a lot of what Babycastles tends to show isn’t meant to run for more than an hour or two without crashing. In a pinch, the collective also has custom-built programs to handle problems with the games.

“We found all this crazy software – Windows hacking shit – that helped us turn these computers, usually Windows XP, into these unbreakable games,” Gupta says. “That’s really important because we’re trying to build this thing that stays in a place and requires maintenance, reliably runs games, doesn’t need any tech help, stuff like that.”

The arcade cabinets themselves are the arts-and-crafts part of the job: Babycastles has done everything from wedging computer parts into stuffed animals to building their own cabinets. Volunteers – both Gupta and Salahuddin say they like to involve as many as possible with this stage, since you don’t need much tech savvy – paint the cabinets and make custom marquees for the games in them.

Harpooned‘s cardboard marquee was split in half, and had a small harpoon cutout – and included a small harpoon cut out; PeaceMaker used, go figure, a large cardboard peace sign.

Sometimes Babycatles has to pay developers to show their work; the cash usually comes from a donation box and a fee at the door – usually around $5 or $10, any bar money for temporary liquor licenses given to art openings nothwithstanding. Two grants from the Warhol Foundation and a local building surplus outfit rounded out Babyhavester’s almost $2000 budget and materials.

But even more than showing off more games, Babycastles is keen on growing their organization.

“Babycastles legally is just me and Kunal, but that’s a lie, right? Because it’s actually a lot more people,” Salahuddin says. “Formalizing that [as a non-profit] is a really important thing we want to do – defining roles, literally hiring people for these positions that they’ve been doing at Babycastles, getting a revenue model.”

The goal is basically to become a fully-functioning, self-contained organization that doesn’t eat up all of their free time. It’s an ambitious goal that will take time and energy. In the meantime, Gupta and Salahuddin need to research and apply for grants, though the formalization of Babycastles is merely a short term goal.

And long-term? Find permanent space in New York City.

“[Our ideal venue] is a DIY punk space, but for games,” Gupta says. “Like a game development madhouse or something.”

In a perfect world, here Babycastles would host exhibitions and works-in-progress, offering artist residencies, as well.

The idea isn’t unprecedented. LA Game Space, a nonprofit center for games research and art exhibitions, found success with Kickstarter last December and is planning to open its doors this year. Gupta thinks a Babycastles venue could help build a “good underground economy” for independent developers – giving them resources to build and showcase their work.

Though Babycastles has been all over (they’ve traveled to Paris, Dublin, Rotterdam, Chicago and Pittsburgh, to name a few) they’ve found you can only teach so much about what the organization does. Part of it just comes from living in New York.

” I think in some ways [our roots] kind of get us – [not having a permanent venue] takes away from some of those, for lack of a better word, punk roots or whatever,” says Babycastles member Ben Johnson. “Having a chance to really get into a space and own it and turn it into something and kind of have this permanent expression of Babycastles. We miss that, I think.”

But changes can’t happen without a fundamental shift in Babycastles’ structure.

Volunteers come and go – not surprising, considering most members have day jobs. New roles are developed. People fill them. Existing members contact friends and others that might want to help out. Reaching out to indie developers to figure out what would make an optimal space is also important.

For now Babycastles is in a period of flux, working on their future while simultaneously trying to stay involved with the indie scene. A big part of that is New York itself.

———

New York isn’t home to many big video game publishers or multi-million dollar titles. Most big game studios tend to find homes on the West coast or in Canada (especially San Francisco and Montreal). And it’s that lack of local industry cashflow that helped form Babycastles’ indie identity.

“Babycastles really feels like something that needed to happen in New York, which is weird because New York really isn’t associated with game development in the way that cities like San Francisco or Los Angeles or Montreal are,” Johnson says, having in the past worked at EA’s offices in California. Instead, Babycastles has come of age in a city known for its support of the arts.

“New York City has always been a mecca for creative people,” says Lantz.

“Those people are drawn to New York City,” he says. “Especially if you’re interested in doing work that is original and different and new and kind of breaking ground and maybe taking risks and doing things that are exciting and contemporary.”

These days, Lantz says that video games now fit on that list of reasons why creative people flock to New York. It’s also a place where word of mouth spreads news around fast.

“I think something Babycastles has benefitted from is that we’re something for people to talk about,” he says.

The talk tends to happen online, through social networking and regular email blasts detailing new projects and other gaming-related events.

Gupta and Salahuddin argue that Babycastles wouldn’t have turned out the way it has without New York. You can teach curation and infrastructure, but New York supplied the people, the interest and the culture.

“There’s an infrastructure element to it, which we teach around the country and world, and I don’t know how it expresses itself in those places,” Gupta says. “[But] that’s it. It’s the raw elements – I don’t know what it turns into as a culture. But in New York, you put those raw elements in and you end up with something like Babycastles.”

“There’s a history in New York of the DIY punk scene that supports all of that,” Salahuddin says. “We did nothing and people showed up. They’re like ‘oh, yeah, I’m down the block.'” A permanent space for Babycastles wouldn’t just be good for the indie community, then, but in its own small way for New York’s cultural heritage itself.

“New York games are expressing themselves by having a venue at all,” Gupta says.

Not everyone quite “gets” Babycastles. The indie games, the memes in the collective’s newsletters, the do-it-yourself arcade cabinets, the themed exhibitions and general eccentricity – it can all be a bit disorienting at first. You think arcade and maybe you get images of Dig-Dug or Street Fighter – more of a Dave & Buster’s than a Duke Reuben’s. Babycastles’ volunteers have seen people come in and experience the unexpected.

“Their minds are completely open to just coming and seeing what it is because they don’t understand,” Johnson says. “I think there’s something really beautiful about that. I think that lack of preconceptions about what going to a place to play a videogame might mean has really benefitted us.”

Still, the collective isn’t worried about being misunderstood. The priority is on showcasing games and bringing like-minded people together. It may be the arts, it may be education, it may be culture or it may just be curiosity that they think will drive the project forward.

“Everyone is basically in on the ideals of this project in this city,” Gupta says.

They just don’t realize it yet.

———

Follow Andrew Freedman on Twitter @andrew_freedman.