Empty Stomachs

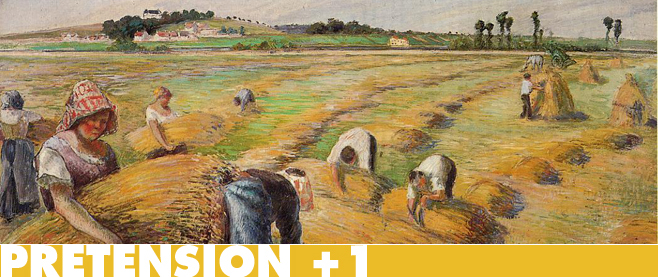

Winter has come. I spent the warmer seasons toiling in the field sowing wheat. I chopped wood and gathered reeds from the pond and used them to add a room onto our ramshackle farmhouse. Soon, my newborn son will be able to lend a hand, tending to sheep and cattle. But for now, as the chill winds whistle through the gaps in the lumber walls of my home, I realize that I have made a terrible error. Rather than expand my house I should have built an oven to better stretch this year’s meager harvest of wheat enough to feed wife, son and myself. As it stands, I can crush the raw meal into gruel that might satisfy the boy, but if my wife and I are to survive the winter I will have to take my moth-eaten hat in hand, trudge into town and implore my neighbors to open their larders to me. When it comes to keeping my family alive, yes, I will beg.

Ask me 10 years ago what I though videogames should be about and I would have told you that they should make the player feel empowered. With the touch of a button they should allow you to scale a building, hurl a car or even take to the sky like a bird. My tastes have changed since then. All those things are well and good, but now I much prefer the moments where everything is going to shit, when I am crushed to death by a giant rock in Spelunky or when hull breach, oxygen fire and alien boarding party ensure that my FTL spacecraft will never make another leap.

My tastes started to change around 2008. I was living in Minneapolis and hanging out with a bunch of like-minded nerds. Once a week we’d meet to play card games like the Game of Thrones CGG and Race for the Galaxy. That year the new hotness was a game called Agricola by Uwe Rosenberg. The game was much like the quintessential Euro game, Puerto Rico, in that players act by choosing different roles each turn. In Agricola, if you need to wood to build something, you put one of your workers there. Then the next time your turn comes around you put another on the spot that lets you build. Of course, you’re not playing in a vacuum. Other players might decide that they need wood and gather up all the lumber that has been accumulating on the spot. Or they might snake your efforts to build an oven, forcing you to wait until the next year to get that improvement.

My tastes started to change around 2008. I was living in Minneapolis and hanging out with a bunch of like-minded nerds. Once a week we’d meet to play card games like the Game of Thrones CGG and Race for the Galaxy. That year the new hotness was a game called Agricola by Uwe Rosenberg. The game was much like the quintessential Euro game, Puerto Rico, in that players act by choosing different roles each turn. In Agricola, if you need to wood to build something, you put one of your workers there. Then the next time your turn comes around you put another on the spot that lets you build. Of course, you’re not playing in a vacuum. Other players might decide that they need wood and gather up all the lumber that has been accumulating on the spot. Or they might snake your efforts to build an oven, forcing you to wait until the next year to get that improvement.

All this jockeying is interesting to be sure, but what really grabbed me was the way that failure loomed around every corner. In Agricola you must feed your family after every harvest, or be forced to beg and lose points. This is the harsh kind of punishment that I would have balked at a decade ago, but that ax hanging over your neck makes every decision, even the most mundane, seem that much more portentous. I had never witness what board gamers call “analysis paralysis” until my Minneapolis group started playing Agricola.

The type-A members of our group would furrow their brows over their plans, sussing how many turns they’d have to wait until the goods they needed would accumulate and carefully counting their livestock to ensure that they’d get the maximum score at the end of the game. Such thinking is a rabbit hole easy to get lost in – and any plans made could easily be toppled by another player’s actions.

[pullquote]Part of me wonders if I haven’t come to appreciate games about a particular kind of struggle because I’ve found a somewhat comfortable place in my life.[/pullquote]

Around the same time, Gamespite writer Jeremy Parrish introduced me to Shiren the Wanderer – a scion of the dungeon crawler Rogue by way of Japan. In this somewhat rudimentary role-playing game you play a samurai on a grueling quest. In addition to your hero’s health, you must also make sure that his stomach is full. Push Shiren too hard and he’ll pass out and wake up at square one having lost all the weapons and strength he’d worked for. Starvation is one of the many ways to go in Rogue, Mystery Dungeon or NetHack – the need to feed adds a second, vital layer of tension to the games. You can’t just mill around in the dungeon forever. You must keep pushing forward, hoping to find the next can of tinned meat or rice ball.

If you haven’t read Pacifique Irankunda’s somewhat damning examination of the gamer’s fascination with war, you should. It’s a very personal piece that describes the young student’s harrowing life in war-torn Burundi and the culture shock he experienced on an American campus when he saw young men transfixed by the kind of violence he had struggled to escape.

Part of me wonders if I haven’t come to appreciate games about a particular kind of struggle because I’ve found a somewhat comfortable place in my life. My bills get paid on time (mostly) and I don’t worry about where my next meal will come from. It is a life many others could only dream of. I am very lucky to live it. Planning for the winter in Agricola or scrounging through a dungeon for food in NetHack allow me to play at living without a safety net. Even though, gratefully, mine is very unlikely to slip away.

———

Pretension +1 is a weekly column about the intersections of life, culture and videogames. Follow Gus Mastrapa on Twitter @Triphibian.