Lemons, Trawlers and a Bit of Alright

Up and down the United Kingdom, wherever game developers gather together in one place, people play a game called Lemon Joust. Its origins are shrouded in mystery; nobody knows who invented it or where it originally came from, but the rules are simple.

Each player gets one lemon and one wooden spoon, and must balance the former on the latter. They use their spoons to try and knock others’ lemons to the floor – but must do so without disturbing their own. Variants include having an extra spoon (the attack spoon), and having two spoons with two lemons. If you leave a pile of fruit and wooden spoons lying around at a game design conference, someone will know what to do.

Without warning and too fast for me to stop – yet somehow slowly enough to be comical – my lemon wobbles off my spoon and hits the floor. I’m at Bit of Alright, the unconventional London game design conference where physical games like this get an airing alongside their digital siblings.

This year it’s on a converted East German fishing trawler called the Stubnitz – all black piping and metal guts like Level 3 of a space marine videogame<. In the crowded rear hold, I am learning what happens when you try to move your lemon too quickly. I’m losing before anyone even touches me.“By around 2006 it seemed really obvious to me that commercial concerns had put games in a cultural straitjacket,” says David Hayward, who founded BoA intending to provide a space for just this kind of physical play. “I’ve seen a bunch of conferences try to work games and play into their programs in really clumsy and broken ways. Usually, that’s because it’s too controlled and overcomplicated.”That isn’t a problem here; the atmosphere verges on chaos. At the aft end of the hold two grown adults are trying to squeeze each other into submission as part of a competitive hugging game called Hugatron.

Others run back and forth in circles around an oblivious woman strapped into an Oculus Rift, chasing after glowing controllers. Meanwhile, on deck, someone is stepping clumsily between taped-down pieces of paper as part of a live level design workshop. All these games involve what Stephen Morris calls “dispensing with the screen altogether and instead focusing on each other.”

Morris is the designer of Glow Tag, which is what the runners were playing. (Everyone puts their controller in their back pocket, so you only know you’re “it” when everyone starts coming at you.) He also designed a duelling sim called Quick Draw, where accelerometer-equipped PlayStation Move controllers stand in for smoking six-shooters.

“Digital games are still primarily a solitary experience, and physical multiplayer games harken back to the childhood playground experiences,” he tells me. “There is something fundamentally different in interacting with a human being rather than a flat screen.”

He’s clearly on to something: physical play is in the air. Last year saw the popularity of Move-enabled party game J.S.Joust and the Kickstarting of MaKey MaKey, a wiring kit which lets you make a controller out of anything that conducts electricity. This May, we had the inventive “Object Jam”, in which all game ideas must be playable with physical objects.

Of course, people have always played Frisbee and football in the park – but most of the people experimenting with physical play at BoA have day jobs in videogames. This is a new kind of engagement with physical rules, one which resembles at first glance some Edenic attempt to escape from the grasp of computers.

In fact, one reason for this “physical turn” is that the principles of game design hold true whether in digital or physical space. One developer I find jousting in the aft hold is Nat Marco, co-founder of UK design house Honeyslug, who’s organizing a game jam about making games with actual jam.

“I think the essence of a good game is the design, and you don’t need to be able to program to be able to do that,” she says. “Games have been around far before computers, so why not make games from physical stuff as well?”

Moreover, she notes, physical design has lower barriers to entry than code; anyone can pick up a spoon and a fruit and get lemon jousting, and that acts against the danger that people will get distracted by new tech and lose sight of what’s important. As Marco tells me: “I always design on paper first. If it’s fun on paper, it’s fun in code.”

That becomes literally clear when I go topside to watch the paper-based level design workshop. Its organizer, Jonathan Whiting, lays down a basic mechanic: you can only stand on paper, not on bare deck. Armed with this simple rule, everyone divides into groups and starts making more complex challenges.

“Level design is primarily concerned with creating an experience within a set of constraints, a ruleset,” Whiting will tell me later. “The techniques for exploring, teaching and exploiting the game’s rules are exactly the same.” Sure enough, familiar patterns emerge: as the no-step rule transforms simple arrangements of paper into challenges, the builders must balance their difficulty and vary their pace.

Of course, some have broken the workshop rules and are already adding new mechanics. Marco’s team, for instance, has added a stockpile of paper for players to pick up along their route, and are debating whether they should start charging for it.

But if design principles can cut across media, objects also assert their own unique properties. Within moments, the paper starts blowing about the deck and the builders are running to catch it. One team modifies their game by tearing the paper to pieces and building very thin lines; later, they stick paper to vertical surfaces to create wall-running segments.

Meanwhile, Marco’s team has taken to writing “L” and “R” on each piece of paper. Without really expecting to, they introduce a new dynamic: put two right feet in a row and the player will need to hop. The players are innovating, exploiting the inherent affordances of their materials to craft new possibilities and new vocabularies.

Whiting is sanguine about these unexpected developments. “My favorite thing about using the real world as your medium is you get access to all these really dense and complex systems for free,” he says. “Similarly, simply running and jumping can be endlessly fascinating in the complexities of a real world environment.”

In that sense, Marco’s jam game jam is as much about exploring the possibilities of the materials it uses as it is about the games that are made. “It’s gloopy so it can be thrown, dropped and mixed,” she says, “It’s also sticky, so things can be stuck to it like a tasty glue. Jars can be used as receptacles for things to be thrown in, pulled out of, or collected.”

Games made included fruit-based tower defense, jam-jar tapping rhythm action, and “Lictionary”, where one player draws a picture in jam and another player (with her eyes closed) must taste it to guess what it is. “I did one last year with rocks, and that went down very well,” adds Marco, matter-of-factly.

Perhaps the most striking example of object-oriented game design is George Buckenham’s Punch the Custard. Buckenham is a designer who has been instrumental in launching physical games across London, especially at Wild Rumpus, Venus Patrol’s regular gaming party that he helped found.

The substance he passes round at his BoA talk (“Don’t eat it! My hands have been in there!”) is not actually real custard but a strange artificial powder, mixed with water and heated to produce a gloopy uncustard which repels your finger if you poke it hard but warmly accepts it if you use a softer touch. Buckenham hooked up players to a MaKey MaKey set and had them compete to see who could punch the custard quickest. “Actually, I think the game was probably less entertaining than just playing with old custard,” he grins at the audience. “I took an exciting thing and made it more boring.”

Here, physical game design acts like a kind of collage, jerking objects out of old, familiar contexts and into new rulesets which transform their meaning and make them strange. Conversely, designing for objects can also mean you discover them anew on their own terms, engaging with their properties in unexpected ways. Buckenham points to a video where ISS astronaut Chris Hadfield plays physical games designed to work in zero gravity and hacked together out of spare space materials. Then again, says Buckenham, code is material too. “It’s not like code doesn’t also have a grain. There are things that are easier to do in Unity, things that are harder to do.”

Still, as materials go, physical reality is pretty easy to design for. There’s more than enough of it for everyone and it doesn’t disappear during a power cut. “Whenever you go to conferences, there’s always game jams,” says Marco, just before starting her jam jam, “and usually only coders can take part. I wanted to do something where everyone could make a game. Using ‘reality’ as middleware, there are no obstacles to getting started.”

Likewise, Buckenham tells me: “A big advantage of designing for reality is that it’s much quicker to be able to change the rules. There’s a physicality to designing stuff in the real world which means far less of a disconnect.”

On the other hand, says Whiting, “the setup requirements of physical games are problematic. To play badminton you need a badminton court. To make a game about piloting a jetpack you need to invent a jetpack.” Even Move-enabled games like Glow Tag and J.S. Joust tend to only be played at events and conferences like these because buying all the controllers they need does not come cheap.

Buckenham agrees: “I was fortunate to have found this interesting substance which feels good to punch or poke, but there’s not much I can do to change the properties of that without becoming a materials scientist. One of the magical things about videogames is that you get to create this entire world – and you can change what the rules are.”

But now we come to the final twist in physical space: rules are very different there. Hugatron, created by two designers named Andrews (Smith and Roper), depends far more than most videogames on sportsmanship and consent in order to work. “The possibility space in Hugatron is vast – almost infinite,” says Smith, a former AAA developer who worked on the ill-fated All Points Bulletin before starting his own studio. “But the sportsmanship is defined by the players and what they’re comfortable doing.”

It can be genteel – I’m actually playing the game while I interview him, and clock up a relaxing 10 minutes in a clinch with a stranger – but later I watch a game which looks more like amateur hour at a judo club. “No blood,” adds Smith, as a good baseline rule.

In this sense physical games, without a computer to enforce their rules automatically, are defined far more by the willingness and fear of players. A week after BoA, at another conference called GameCamp, I play a game of blindfolded gun-fighting and unwittingly cause a silent debate among the referees when I feel my way to a desk and start camping behind it.

“You bring yourself to this, and it’s quite interesting to see how far people go with it, within the bounds of taste,” says Smith. “People who are friends are more competitive, because they know each other’s boundaries.” An office Christmas party, he claims, is the optimal setting for a good game of Hugatron: the perfect mix of awkwardness and intimacy.

Moreover, in the absence of a computer, natural enforcement mechanisms step in. Like Hugatron, you can use an actual referee (it needs one, in case lines are crossed), but as Morris points out, sometimes these games are self-policing. “The primary problem is ‘negative’ players – the ones who instinctively refuse to cooperate,” he tells me. “But if an individual is deliberately bringing the game down, the other players will eject them from the game.” One Quick Draw player realized he could win by sitting down and laying the controller on the ground. “He was very quickly ostracized from the group,” says Morris.

Perhaps, then, it’s better to think of sportsmanship and other constructs as extra rules for the game – unarticulated ones, but rules nonetheless, invisible networks of cause and effect that surround and permeate the playspace. Through social pressures, their enforcement can be as swift and harsh as any bot’s.

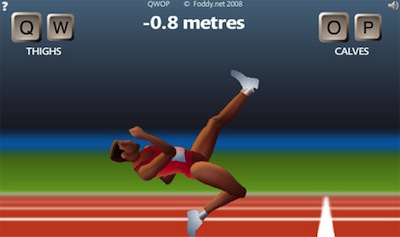

Bennett Foddy, a philosophy professor who built a giant trampoline game at 2012’s GameCity event (as well as a little thing called, oh, QWOP), told me he’s interested in making physical games “because they easily harness existing social practices around group spectatorship and performance. If you’re playing a game on a stage, in front of hundreds of other people, it takes on all the importance and weight of a spectator sport.”

To the list of objects which bring their qualities to a physical game we must add “society” and “the human animal”.

That seems very far from the guiding ethos of the AAA games industry as embodied by the Xbox One launch, which went off like distant fireworks during my interview with Buckenham (and also involved the word “immersive” being splashed on a giant green screen).

“Live or physical games are perfect examples of games that aren’t escapist in any sense,” argues Foddy. “If you’re controlling a game with your own body, you’re not a superhero or an athlete or a cyber-soldier – you’re just you. Your limitations are the limits of your own body.”

In an interview with Eurogamer, Microsoft’s games chief, Phil Harrison, claimed that games are fundamentally about “wish-fulfilment.” As Foddy dryly shot back: “The only wish that videogames fulfil for me is that I wish to be playing a videogame.”

Yet for all that the industry likes to insist that videogames can take you to a faraway place away from your body and your life, Buckenham is keen to stress that even this is a fiction. “Videogames depend just as much on the exact feeling of the controller in your hands. With physical games you’re foregrounding it, and you’re having to do a bit of design work, but it’s not any more of a physical or holistic experience.”

Alas, that argument didn’t do him any good when he submitted Punch the Custard for a videogame BAFTA. “It wasn’t a videogame, they said!” he laughs. “And then they apologized for saying that, but they still didn’t put it in.”

Well, screw them. We’re having too much fun waving spoons menacingly at each other like a bunch of children. In a world already bound by rules and social practices, are the makers of physical games trying to break down barriers? “Yeah, I think I am!” says Buckenham.

“There’s something really satisfying about this sort of thing, as long as you reward that trust. The feeling of safely breaking through those barriers is something that feels amazing.” Whiting cites a sense of I’m-worried-I’ll-look-silly embarrassment which sometimes gets in the way – likening it to a reluctance to dance while clubbing – but he’s found that people are pleasingly open to physical play once they’re nudged in that direction. “I think you can squeeze a lot more out of life if you learn to push past those feelings,” he says.

It would be easy to claim, like a market pusher for gamification, that their barrier-breaking effect persists beyond the magic circle; that they can turn us into happier and freer human beings (or even, God forbid, happier and more productive workers). But everyone I interviewed was cautious about any wider utility for physical games.

Buckenham in particular is skeptical that play-based “nudging” works in any grand way. Instead, he claims, it’s just a nice thing to do. “It directly connects to having a joyful life, both for me and the people I’m playing with, without needing to play a part in some larger scheme or agenda.” For all it reveals about game design and about the fabric of the things we make games with, physical play need be nothing more than giggling over a bunch of lemons at a party.

“Doing stupid things,” concludes Buckenham firmly. “Doing stupid things is pretty popular.”

P.S. I won the Hugatron record.

———

Follow John Brindle on Twitter @john_brindle.