What Matters Is What You Don’t See

One of the most interesting things about 2D games is that, by definition, they are abstract. No matter how real the world they are trying to depict is, 2D games are less representational because, well, there’s an entire dimension missing. This allows one to experiment with the game’s design in ways that just wouldn’t be possible if you were depicting a 3D space.

[pullquote]One of the most interesting things about 2D games is that, by definition, they are abstract.[/pullquote]

I discovered working on Mark of the Ninja that seemingly small presentational changes afforded by working in 2D can have a large impact on the way a game actually feels. When we changed what the player could, or rather couldn’t, perceive in the game, it had a tremendous impact on how players interacted with the world of Ninja. By limiting the player’s field of vision, Ninja moved from feeling arcade-y and artificial to tangible and dangerous.

“Fog of war” – the practice of obscuring any part of the game that lies outside the player’s range of vision – comes from real-time strategy games, where its inclusion is practically mandatory. And for good reason – scouting and partial information are key components of the ‘S’ in “RTS.” Games in 3D already have the same natural “fog of war” we have in real life, where either the first-person viewport or over-the-shoulder 3rd person camera limits your perception of the world to a fixed angle. If you want to see what’s behind you, you have to turn around.

2D games lack this natural limitation, however. What is displayed to the player is divorced entirely from what the player character could reasonably see, unlike a first-person game, where what the player sees is precisely what the character sees. By their very nature, 2D games will show a portion of the game world that is outside the character’s field of vision. It’s up to the designers and artists to determine what the player should be able to see and more importantly, why they should see some things and not others. This cuts both ways – sometimes you’ll see what is above your character even though there’s a full solid floor in the way, but you can’t see beyond the edges of the screen, even though your character could certainly see down that long corridor just fine.

Ultimately, 2D games confine what can be perceived by their screen size. If you want to see what’s off the screen, you need to walk over there. Some games bind their screens to physical spaces – think of the dungeons in the original Legend of Zelda. Some may advance the screen automatically, and the player dies if they move offscreen (which is actually really weird if you think about it, but it’s such a convention that at this point, we all just kind of accept it). Most just frame the screen on your character though, using various tricks to bias where it is centered. As an aside, this explanation of the camera in Super Mario World is fascinating.

Ultimately, 2D games confine what can be perceived by their screen size. If you want to see what’s off the screen, you need to walk over there. Some games bind their screens to physical spaces – think of the dungeons in the original Legend of Zelda. Some may advance the screen automatically, and the player dies if they move offscreen (which is actually really weird if you think about it, but it’s such a convention that at this point, we all just kind of accept it). Most just frame the screen on your character though, using various tricks to bias where it is centered. As an aside, this explanation of the camera in Super Mario World is fascinating.

In Mark of the Ninja, we wanted something closer to the limitations of perception a 3D game provides – you can only see what your character sees. Ninja has a fog of war that hides objects and enemies who fall outside a cone projected out from the player that is meant to simulate their vision. (In New Game+, the player is further limited to see only what is in the direction they are facing.) The level art itself is blurred and its colors are muted. Basically, what the player can perceive is much closer to what the character could perceive. It also encourages the player to behave as if they were trying to gather information. If they need a vantage point on what’s below a wall, they have to go get on top of it. This enhances the feeling of espionage, of gaining knowledge your opponents don’t and generally just being a sneaky devil.

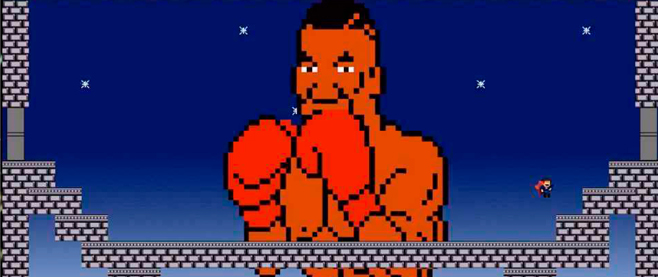

Before I joined Klei for Mark of the Ninja, Klei had made a 2D brawler called Shank. And compared to Shank, the amount of information presented in Ninja is quite different. Most notably, Ninja generally pulls the camera out much further. The player character is smaller on screen, where in Shank the camera often zooms in much tighter, especially during an intense fight or something similar. In a beat ’em up like Shank, this kind of detail is important; you can see the tells enemies make before certain attacks, see when your own attacks have landed, know when you can branch into the next stage of a combo, etc.

Initially we had difficulty in dissuading players from treating Ninja like a beat ’em. If players were spotted while being stealthy, they’d immediately resort to melee combat. There were a lot of reasons for this, but I think what players could see and how they could change what they were able to see played a part in that. The game looked like a beat ’em up, so players treated it like one. When we introduced the fog of war, it slowed down the pace of play. The game felt different, and people treated it differently. They treated it like a stealth game.

These are largely things we’ve come to realize in hindsight. I started thinking about this due to two other games I played recently – Teleglitch and Monaco. Both are 2D games that use fog of war in interesting ways to create different aesthetics. Both are top-down, but while Monaco is about stealth and Keystone Cops-esque chases, Teleglitch is about unrelenting tension and scarcity. In Teleglitch, your vision is limited conically, but anything you can’t see is utterly black. Did that room you just flee from have an exit on the far side? Were there resources in there? How many places could enemies come at you from? These questions ricochet around your skull, but answers are nowhere to be had. You have no choice but to plunge back into the dark. (Incidentally, I can’t think of many top-down 2D mouse and keyboard games that have good “control feel” but Teleglitch feels great. There’s a free demo you should really play.)

These are largely things we’ve come to realize in hindsight. I started thinking about this due to two other games I played recently – Teleglitch and Monaco. Both are 2D games that use fog of war in interesting ways to create different aesthetics. Both are top-down, but while Monaco is about stealth and Keystone Cops-esque chases, Teleglitch is about unrelenting tension and scarcity. In Teleglitch, your vision is limited conically, but anything you can’t see is utterly black. Did that room you just flee from have an exit on the far side? Were there resources in there? How many places could enemies come at you from? These questions ricochet around your skull, but answers are nowhere to be had. You have no choice but to plunge back into the dark. (Incidentally, I can’t think of many top-down 2D mouse and keyboard games that have good “control feel” but Teleglitch feels great. There’s a free demo you should really play.)

Monaco shows visible areas you glimpsed but can no longer see as a blueprint. You can make out doors, passageways, labeled areas. Not only does this reinforce the whole “heist caper” theme, but it allows for scouting and planning. Additionally, in co-op, all the visible areas are shared between players. One player can be a scout, making sure their vision cone is pointed in an area everyone wants to know about. But the fog of war is essential to Monaco feeling like a sneaky heist caper. If you could see the entire game without fog of war, the game would basically become Pac-Man. Monaco may be at its best when you’re hustling away from a guard dog and blunder into a room you couldn’t see – only to find three guards waiting for you inside and all hell breaks loose.

Small changes can have tremendous impact. These changes can affect how a game feels, what it is fundamentally about at its core. It’s one of the things about game design that I continue to find fascinating. While I do love 3D games, one of the things I really like about 2D games is that abstract nature makes experimentation in this regard viable, simply because we aren’t trying to depict a perfectly representational space. The more experiments people can do, the more likely we’ll get that weird alchemy that coalesces into great, interesting games. And more of that weirdness is something I’d heartily welcome.

———

Nels Anderson was the lead designer of Mark of the Ninja and probably the only game developer in all of Canada born and raised in Wyoming. You can follow him @Nelsormensch.