Who Am I, Really?

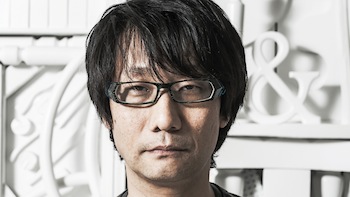

Man, that Kojima.

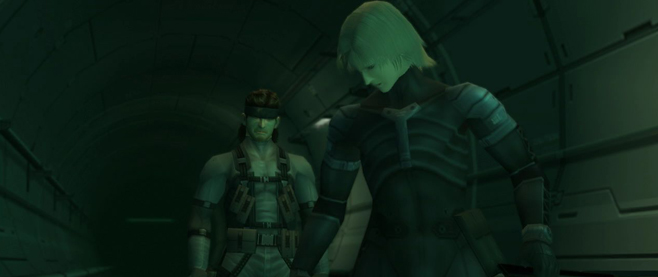

It’s arguably a sentiment that no one who plays games can really escape while making their way through Metal Gear series creator Hideo Kojima’s postmodern masterwork, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty. It is also one that I had not experienced until just a couple of weeks ago, a dozen years after its initial release.

Criminal.

[pullquote] It’s not as if I hate Deus Ex now. It’s more like seeing a one-night stand in the light of day.[/pullquote]

I’m embarrassed to admit now that until a few months ago I knew little of Metal Gear‘s infamously intricate lore beyond the name of its longtime protagonist, Solid Snake. Then, at the behest of my best friend (Unwinnable’s own Steve Haske), I bought Metal Gear Solid on PSN and struggled my way through it.

While the game’s story and voice acting had me hooked, its gameplay – especially the combat – left me writhing in frustration. At the time I had just finished Spec Ops: The Line and found the transition to MGS’ 32-bit, top-down gameplay jarring.

By the time of its release in 1998, I had developed a disdain for the puny computing power of the PlayStation, instead embracing graphically-advanced PC games like Half-Life. Those formative years had left me a little helpless when it came time to play MGS. (As a full disclaimer, Steve had to help me finish the game, as he knew it would simply languish unplayed for eternity otherwise.)

However late I may have been in paying my console dues, the humiliation I suffered at the hands of Kojima did not leave me champing at the bit to play Sons of Liberty, but I forged ahead regardless. I shouldn’t have worried.

Thanks to the commendable 60-FPS polish Bluepoint Games gave MGS2 in Metal Gear’s HD Collection, nothing aside from a few control quirks felt archaic (the sequel’s jump from PS One to PS2 didn’t hurt either). I was able to plow my way unaided through the game in a matter of days.

A strange thing happened as I wove my way through Big Shell, the oil decontamination plant where the bulk of Sons of Liberty’s labyrinthine plot comes to fruition. Progressing deeper into the game, I found myself becoming more and more distracted, my thoughts continually circling back to Deus Ex, a contemporary of Kojima’s first PS2 outing.

The reason I never played MGS2 during its initial release was my hardcore PC gamer sensibilities. Back then I had not yet come to fully grasp the untenable nature of the hardware arms race, still generally the unfortunate rubric through which PC players measure their worth. Deus Ex – Ion Storm’s cyberpunk adventure game released just one year before Sons of Liberty – has, for me, long represented the apogee of PC gaming from that era, with smart, open-ended design, a compelling story and meaningful gameplay choices.

If only I knew then what I had been missing out on. After I completed MGS2 and had started to digest the insane meta-nature of its narrative’s final hours, I realized that my worldview had been forever changed.

Perhaps I wouldn’t be so deeply disturbed by this latent revelation if not for the fact that on the surface level, Deus Ex and Sons of Liberty actually share quite a lot in common. Both games are set in a rapidly-changing near future (well, near-future for 2001, anyway) where nanotechnology and shadow organizations shape the world, making prescient predictions about how technology would become an increasingly important factor in our lives.

Both also offer challenging setpieces that can be solved in multiple ways depending on your play style and the gadgets and weapons you’ve picked up along the way. Hell, each even has an awesome sword that ends up playing a pivotal role. Sadly, that’s where the comparisons end.

Both also offer challenging setpieces that can be solved in multiple ways depending on your play style and the gadgets and weapons you’ve picked up along the way. Hell, each even has an awesome sword that ends up playing a pivotal role. Sadly, that’s where the comparisons end.

I used to think that the conclusion of Deus Ex was profound, but then again I used to be 16 years old. Having recently revisited its three possible endings on YouTube, my heart sank as I watched old JC Denton yap away in his robotic monotone.

I’m willing to forgive godawful, wooden voice acting, since many games from that era had abysmal voice work. What makes me truly sad is that the game takes itself so seriously and yet still manages to say virtually nothing. You never get the sense of what, if anything, Ion Storm wanted you to take away from the experience.

In the final moments of Deus Ex, the player can either choose to silently rule the world as a member of the Illuminati, merge with a supercomputer (ruling the world themselves) or destroy all technology and send the planet back to the Middle Ages (oh ho, another plot similarity!). It would appear as if you have a serious decision to make, but in reality your agency is severely hampered in how little the game chooses to say about the path you take.

After 20 or 30 hours of gameplay, you get a 60-second cutscene and the credits roll. It’s as egregious a “fuck you” to players as there ever has been. Only the game was so mechanically impressive back then that no one noticed or cared that the ending carried about as much weight as that of the mindless hack-and-slash Diablo II, released just a month later to plenty of fanfare (and with a threadbare storyline).

In some ways, comparing Deus Ex and MGS2 is an apples-to-oranges proposition, but in the most important ways it is not. Creating effective gameplay systems has perhaps in many ways always been what’s most interested Warren Spector, driving the direction of Deus Ex.

Admittedly, its design parameters, with such freedoms as they offered, did work perfectly – likely because they represent a culmination of Spector’s work on System Shock, Thief and a host of other games.

Admittedly, its design parameters, with such freedoms as they offered, did work perfectly – likely because they represent a culmination of Spector’s work on System Shock, Thief and a host of other games.

However, the best games must transcend the set of systems from which they are constructed. Building a Rube Goldberg machine where all the digital gears work in tireless union is not all there is to gaming. It certainly isn’t what fascinates Kojima, who long ago earned the right to call himself a true auteur.

I was left with my own choice to make upon finishing Sons of Liberty. Whenever someone asks me what my favorite game of all time is, the easy response has always been Deus Ex – so much so that I haven’t given my answer much thought at all in years. Could I now continue to defend a landmark PC game as the best its era had to offer, or would I embrace MGS2 as the true embodiment of everything I feel can be compelling about gaming?

In Sons of Liberty, the takeaway offered to players is a far more subtle commodity, one that is perhaps imperceptible if you are among the daft legion of ADD-addled gamers who cannot muster enough patience to appreciate the numerous brilliant cutscenes and character interactions through Metal Gear’s in-game codec communication system.

The stakes presented in the game’s finale are not about what button to push or what player-driven outcome is played on-screen. Instead, Kojima’s rigid narrative gives players the ultimate choice, one of interpretation. MGS2’s final act makes it clear that you are playing a video game; more importantly Kojima intimates that this doesn’t, or shouldn’t, matter.

Essentially, the denouement gives Raiden, and thus the player, a final bit of advice: What you think about the game and what it is trying to say – explicitly granting the precious agency that players seek and too often only believe they possess – is your choice. It is a decision whose outcome will play out not in a well-framed cutscene but long after the console has powered down.

Essentially, the denouement gives Raiden, and thus the player, a final bit of advice: What you think about the game and what it is trying to say – explicitly granting the precious agency that players seek and too often only believe they possess – is your choice. It is a decision whose outcome will play out not in a well-framed cutscene but long after the console has powered down.

The best games, the ones we can call art, are brave enough to say things that might not be understood or appreciated at the time. They are experiences that can shape philosophies or change minds. For me, Metal Gear Solid 2 has done both in ways that I’m still coming to terms with. It’s not as if I hate Deus Ex now. It’s more like seeing a one-night stand in the light of day. It isn’t a bad game, just a very different one than what I might have imagined as viewed through the devious mists of nostalgia.

Perhaps the most exciting thing for me is that I’ve still got so much more of the Metal Gear saga to experience. I’m just about halfway through MGS3 and I have no idea what new revelations lie ahead. All I do know is that I’m going to be saying Man, that Kojima for a long time to come.

———

Owen R. Smith often rants about videogames and the industry on Twitter @inanedetails.