The Rules of the Game

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany, was an Irish nobleman probably best known to the modern mind as a writer of profound influence on H.P. Lovecraft (by way of his excellent short story collection, The Gods of Pegana), not to mention other 20th century fantasists from Tolkien to Arthur C. Clarke. In addition to his massive literary output, which consists of hundreds of stories, plays and poems, Dunsany was also a champion chess player.

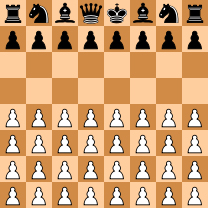

His most interesting accomplishment as a chess master was the development of an asymmetrical variant of the game in 1942, known appropriately as Dunsany’s Chess or Horde Chess. In it, the black pieces are set up in the usual formation on one side. They are opposed by four rows of white pawns. All the pieces move in the traditional manner. Victory is won when the white pieces checkmate the black king or when the black pieces capture all 32 white pawns. If the horde runs out of legal moves, the game is called a draw (you can play a free Java version of the game here).

His most interesting accomplishment as a chess master was the development of an asymmetrical variant of the game in 1942, known appropriately as Dunsany’s Chess or Horde Chess. In it, the black pieces are set up in the usual formation on one side. They are opposed by four rows of white pawns. All the pieces move in the traditional manner. Victory is won when the white pieces checkmate the black king or when the black pieces capture all 32 white pawns. If the horde runs out of legal moves, the game is called a draw (you can play a free Java version of the game here).

Dunsany’s Chess makes the methodical pace of regular chess very hard to maintain. The balance of power between the two sides is precarious and it takes only one or two errors on either side before the game quickly and irrevocably slides out of control. It is an entirely different game than chess, and yet, retains all the original game’s basic rules. Dunsany merely applied them unconventionally.

———

Players constantly look for ways to play videogames in ways the designers did not intend. We probe for glitches, safe spots and mechanics that can be used outside their original purpose. Usually, these exploits merely bestow an unsporting advantage, but sometimes they lead to intriguing possibilities.

One of the best examples of the former was the bunny hop. When playing a multiplayer deathmatch in first person shooter, you would inevitably see someone stuttering across the battlefield like something out of Jacob’s Ladder. It used to be beneficial to move by constantly jumping rather than sprinting forward – the benefits varied depending on the game, but ranged from faster movement to increased accuracy to being harder to hit. The bunny hop is the tip of the exploitative, willfully aggravating iceberg that is competitive multiplayer.

[pullquote]No one is interested in ending the game until the street lights come on and it is time to go home.[/pullquote]

On the other hand, there is Horde Mode in Gears of War 2. In an obvious parallel to Dunsany’s Chess, a team of players has to survive wave after wave of increasingly powerful enemies. One such enemy is the Locust Mauler, who carries a large shield. Once a Mauler is defeated, its shield can be used by players and deployed as cover. At the end of a round, unused or discarded shields would disappear. However, if every player grabbed a shield before the round ended, they suddenly had the means to seal entrances and create makeshift fortifications in subsequent rounds. This created a layer of tactical gameplay that was outside of what the game designers conceived. When the time came to develop Horde 2.0 for Gears of War 3, it included static defenses that could be purchased and deployed – an addition directly inspired by the ingenuity players displayed with the shields in Gears 2.

———

When children play amongst themselves, the rules of play are malleable. Changing the rules – seeing just how much one can get away with before exhausting the patience of the group – becomes the game more than the game itself. Go too far and you are labeled a cheater, but the word doesn’t carry the same stigma for children that it does with adults. Men have gotten shot for cheating at cards, but the worst children usually get is a rude rhyme chanted at volume before play continues unabated.

Remember tag? It starts in an open space – a series of front yards or a playground – and involves a gang of kids running away from the one designated IT. IT has to tag another kid in order to no longer be IT.

The first mechanical problem in a game of tag is that once IT tags a kid, there is nothing to stop the new IT from tagging back immediately. So, the clever IT calls out “No Tag Backs” as the game begins, ensuring that a new IT must always allow the former IT to escape. Other calls modify the game further, as the players find them necessary. Calling “Home Base” near a porch or a singular tree allows you to remain safe from IT there, so long as you remain in contact with it. Call “Electricity” and you can reach out and grab a friend – the IT immunity conferred from the base is extended to them so long as you continue close the circuit. Once everyone is safe on base, IT can call “No Camping” to force them to scatter again.

The first mechanical problem in a game of tag is that once IT tags a kid, there is nothing to stop the new IT from tagging back immediately. So, the clever IT calls out “No Tag Backs” as the game begins, ensuring that a new IT must always allow the former IT to escape. Other calls modify the game further, as the players find them necessary. Calling “Home Base” near a porch or a singular tree allows you to remain safe from IT there, so long as you remain in contact with it. Call “Electricity” and you can reach out and grab a friend – the IT immunity conferred from the base is extended to them so long as you continue close the circuit. Once everyone is safe on base, IT can call “No Camping” to force them to scatter again.

And so on. The game is repeatedly modified to ensure that it continues. No one is interested in ending the game until the street lights come on and it is time to go home.

This open approach to rules carries over to tabletop games, for both children and adults. I have never played a game of Dungeons & Dragons that didn’t have some house rules that tweaked play to a particular group’s style. The same is true for board games – it only took about three rounds of Risk: Legacy before my group started to float ideas on how to change it. This can also happen to the detriment of a game: just take a look at the actual rules of Monopoly and marvel at the fact that you have never played it the right way. Folly or not, these modifications are always in the service of fun.

[pullquote]Take a look at the actual rules of Monopoly and marvel at the fact that you have never played it the right way.[/pullquote]

Once upon a time, videogames were just as pliable. The Konami Code allowed players to get enough extra lives to make the NES version of Contra an enjoyable game instead of an exercise in frustrating repetition. Opening the debug menu in PC games from Doom to Baldur’s Gate gave you complete power over the game world in a few keystrokes while modding communities turned games like Dark Forces and Half Life inside out, the same way Dunsany did to chess.

As competitive online play became widespread, however, concepts like balance gained importance. Games pulled back on their own wild potential. Exploits were quickly patched. Modding communities became curiosities rather than the norm. Winning is the focus.

More and more, the inner workings of play are being closed off to us when they should be thrown open to even the slightest flight of fancy. The real world is grim and full of certainty – death and taxes – but play should never be so regimented. It should be mercurial and full of whim. There, among the ever-changing swirl of make-believe, is always a surprise: the game you never imagined possible, the best one ever – for the moment.

———

Stu Horvath is always changing the rules on Twitter @StuHorvath. Come back next week to share in another Burnt Offering.