The Enslavement of Josef – A Machinarium Retrospective

At the end of Machinarium, the mechanical protagonist Josef climbs a large tower to which the Black Hat Gang has strapped a bomb. He uses a roll of toilet paper – why do robots need toilet paper? – to rappel down the tower and defuse the bomb before continuing on his way.

In the foyer of the tower, at the foot of a grand staircase, a small, grey, destitute robot sits on a perch in the wall, his head bowed, his eyes closed. He is, like most things in Machinarium, dingy and decrepit. But this tower is relatively posh: red carpets, crystal chandeliers, big game animals stuffed and mounted on the walls, signifiers meant to remind us of stately Victorian gentlemen.

If Josef interacts with the robot on the shelf, the poor thing tells a piteous story: a group of soldiers – the same type of soldiers guarding the gates of the city – colonized his radish-shaped home planet and carted him to this tower in pieces. This robot seems to be imprisoned in the tower. Perhaps he is a slave, a victim of robot imperialism.

———

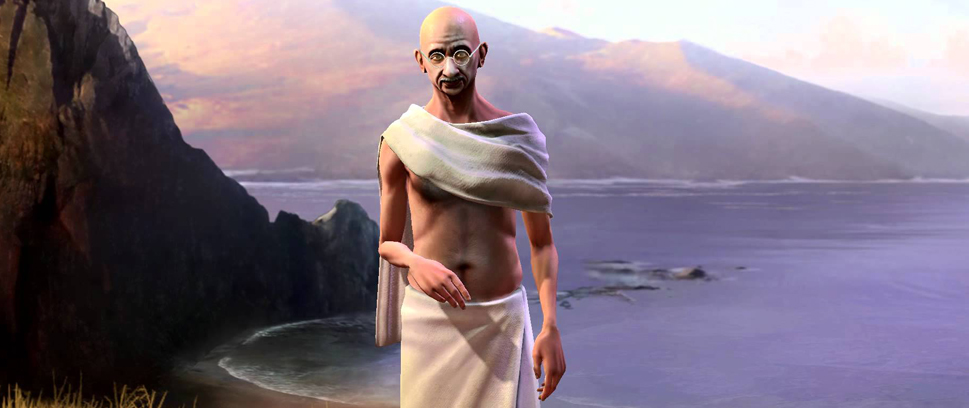

Machinarium emerged in 2009 as Amanita Design’s breakout point-and-click adventure game, noted for its minimalist story, lush, pencil-drawn art direction and moody, evocative atmosphere. As the name suggests, the world of Machinarium is populated exclusively by robots, their city a collection of pipes and cogs and levers and dials and cranks.

Machinarium emerged in 2009 as Amanita Design’s breakout point-and-click adventure game, noted for its minimalist story, lush, pencil-drawn art direction and moody, evocative atmosphere. As the name suggests, the world of Machinarium is populated exclusively by robots, their city a collection of pipes and cogs and levers and dials and cranks.

As such, most of Machinarium’s puzzles involve fixing things: completing electrical circuits, repairing clogged drains, untangling wires. In a way, the game is about restoring order, about creating verifiable, reproducible outputs from very specific inputs. Machinarium effectively marries its setting to its puzzle design, but Josef’s interaction with the little gray robot places the game in a broader, darker context.

———

Josef climbs to the top of the tower, where he finds who is colloquially known as the Royal Robot. A short scene informs us that Josef and his girlfriend were responsible for cleaning and maintaining the Royal Robot’s home until the Black Hat Gang stormed the palace. They exiled Josef, forced his girlfriend into indentured servitude, strapped a bomb to the tower and damaged the Royal Robot badly enough to leave him in a vegetative state.

The scene establishes a power dynamic between the Royal Robot and our mechanized hero: Josef is a servant, and we’re in the presence of what passes for aristocracy in a mechanical dystopia. It also suggests that the Royal Robot owns the downtrodden robot from the foyer.

The elephant in the room is that Josef, too, may have been brought to the city as a slave at some point in Machinarium’s mercurial backstory. This little discovery is perhaps best described as a plot twist, but it informs and reflects every other part of the game, from its setting to its puzzles to its genre, smoothing out Machinarium’s rough edges and giving its mechanics a context beyond point-and-click tropes. It turns Josef’s final act from one of charity or empathy to something more complex.

———

Like most artists, Machinarium designer and Amanita Design founder Jakub Dvorský hedges his bets when it comes to criticism of his work: “Of course, you can interpret [the game] any way you want,” he tells me. “There’s no deeper meaning or message hidden in the story, but we know much more about the Machinarium world, its history and about all the characters than what you can learn in the game.

Like most artists, Machinarium designer and Amanita Design founder Jakub Dvorský hedges his bets when it comes to criticism of his work: “Of course, you can interpret [the game] any way you want,” he tells me. “There’s no deeper meaning or message hidden in the story, but we know much more about the Machinarium world, its history and about all the characters than what you can learn in the game.

“The player should feel that every character has its own story and place in that world, even if it’s not expressed in the game itself,” Dvorský continues.

.

But Machinarium and its world are, if nothing else, meticulously designed, its life and characterization are often tucked into small corners of the world. The colonized robot chained to the tower wall isn’t there by accident, and the idea of Josef’s servitude fits neatly with other themes explored by the game.

———

Machinarium’s world is populated by robots and built on circuit boards, waterworks and quietly whirring machine parts, a setting Dvorský finds “ideal for harder puzzle-based adventure games.” The world feels internally consistent and holistic throughout, both visually and mechanically.

The setting is thematically consistent as well, though. Nothing in Machinarium is abstract or flighty. In a world of machines and tools, every interaction is concrete and predictable. Because we know so little about Josef or what motivates him, though, the puzzles he solves can often seem arbitrary.

In one example, Josef finds a group of musicians whose instruments don’t work. They seem totally unconnected to the game’s larger plot, and Josef has no reason to help them except that they represent a puzzle in the game world. The game’s sparseness works well as a storytelling device, but fails when it has to account for the player’s need to fix a didgeridoo: Josef’s – and ultimately the players’ – actions are unthinking and automatic.

The game forces the issue by hiding critical inventory items behind the successful completion of unrelated puzzles. Their instruments repaired, the robot band performs an impromptu jam session in the street, causing an angry woman in a neighboring apartment to throw a potted plant at them. Josef uses the plant in a later puzzle in a greenhouse, but there’s no obvious link between the two parts of the game.

The game forces the issue by hiding critical inventory items behind the successful completion of unrelated puzzles. Their instruments repaired, the robot band performs an impromptu jam session in the street, causing an angry woman in a neighboring apartment to throw a potted plant at them. Josef uses the plant in a later puzzle in a greenhouse, but there’s no obvious link between the two parts of the game.

Machinarium uses a nested puzzle structure throughout, each conundrum yielding some geegaw or trinket crucial to some other part of the world. Taken on the whole, Machinarium feels efficient and graceful, each section tied inextricably to the next, no stone unturned, no item unused.

The musician section, and others like it, represents a tautology: Machinarium is a puzzle game, and therefore must feature puzzles. Josef the robot must solve puzzles, independent of the game’s plot or any perceivable cause-and-effect. The granular, moment-to-moment play is coercive.

———

Very little of Machinarium’s backstory is made explicit: there is no long-winded exposition or in-game scrolls to find. In fact, there are no words in Machinarium at all – any pertinent information is provided contextually by the environments or, in a few cases, in the form of Josef’s crude thought bubbles. Machinarium’s sparse narrative presentation was designed, according to Dvorský, in order to allow “more space for [the players’] imagination” and to limit the need for expensive and time-consuming animation.

A by-product of this minimalism, though, is that it inextricably couples Josef’s characterization to the game’s mechanics: the only way to understand Josef is in the context of the things he does over the course of the game.

With this in mind, the narrative implications of Josef’s indentured servitude are disconcerting. The Black Hat Gang exile Josef, kidnap his girlfriend, and incapacitate the Royal Robot as part of an ostensibly larger but unexplained plot. Josef eventually rescues his girlfriend, but he also saves his former master before escaping into the sunset in a helicopter.

It’s disconcerting that Josef helps the Royal Robot, as it only reinforces a skewed power dynamic that, as we’ve seen, produces something akin to robo-bondage. With such a limited look into the world of Machinarium, it’s impossible to rationalize or explain Josef’s actions at the end of the game. The most successful slave narratives offer redemption and struggle, but players will never know if Josef is powered by altruism or Stockholm syndrome.

It’s disconcerting that Josef helps the Royal Robot, as it only reinforces a skewed power dynamic that, as we’ve seen, produces something akin to robo-bondage. With such a limited look into the world of Machinarium, it’s impossible to rationalize or explain Josef’s actions at the end of the game. The most successful slave narratives offer redemption and struggle, but players will never know if Josef is powered by altruism or Stockholm syndrome.

A sadder notion might be that Josef simply has no choice – he’s a robot, after all. Automatons don’t need a story to frame or contextualize their actions, only commands. The taxidermied gazelle, the spiral staircase and the “Royal Robot” moniker are cultural signifiers of class and power; the gray robot’s story of imprisonment signifies – if not literal slavery – a lack of context and awareness, a lack of options and autonomy.

———

When asked why the adventure genre was the best way to express Machinarium’s values, Dvorský tells me, “We’ve always been making adventure games – that’s the best genre for us.” I believe him.

Restriction and specificity are traditional hallmarks of the point-and-click adventure, to be sure, but everything in Machinarium serves to reinforce that fact. The idea that Josef is the victim of some sort of robo-colonial slave trade is mirrored at every level – in the story, in the fact that he is a robot, in the structure of puzzles and in the adventure genre generally.

As players, we’re complicit in Josef’s inability to simply ignore a group of broke-down buskers and his perverse willingness to save an aristocratic slaver. But, as Dvorský points out, “Josef … is quiet, non-egoistic, unobtrusive, and therefore it’s easier for the player to empathize with him and feel like him.” Even as we guide little Josef through Machinarium, the team at Amanita Design guides us, constantly narrowing our options and ferrying us through the game world.

There’s obviously no comparison between real-world slavery and playing a videogame, but Machinarium reminds us that the world is full of top-down systems, that to play is to give up control, to acquiesce. Jakub Dvorský was kind enough to invite us into his charming world, but only on the condition that we obey its rules, just as Josef obeys his – whether they come from the Royal Robot, his own robot programming or us.