City of Refuge

Bluesman Tim Gearan has been doing it right here in Cambridge for years. There’s something undeniably fun about his music, tunes that keep you dancing even as the gravel in his voice speaks of years of hardship. One time, back when he used to play regular Monday night gigs at Toad in Porter Square, the whole band – horns and all – stood up in the middle of a song, marched in single-file across the street to the Dunkin’ Donuts, bought coffees and walked right back into the venue, with the crowd following behind. They kept playing the entire time.

But the joy of Tim’s performances, to me, isn’t in stunts like that. It’s the way his songs feel instantly familiar, like buried memories suddenly unearthed by a chance sight or scent. And like old memories, his songs often contain a strange mixture of comfort and darkness.

[pullquote]NYC in “The Darkness” is … setting as emotion, an inhabitable metaphor, where the player’s physical exploration of the space mirrors his exploration of the story’s theme.[/pullquote]

My favorite track is “City of Refuge,” off his 2007 album No Remedy. The refrain “I’m gonna run / I’m gonna run / I’m gonna run to the City of Refuge” is taken from the 1928 classic of the same name by blues legend Blind Willie Johnson. Tim’s version mixes the apocalyptic with the irreverent: a menacing tri-tone riff from the horns counterpoints Tim singing about Jesus “passing out his homemade wine.” Oblique references to a vengeful Old Testament God are interspersed with slick slide guitar runs. The end times may be upon us, but at least they have a funky soundtrack.

———

If Starbreeze’s 2007 shooter The Darkness were a song, it’d almost certainly be a blues tune. Like the 12-bar blues, the game has a repetitive structure: the setting alternates between present-day New York City and the Otherworld, a horrific WWI-era version of Hell. Protagonist Jackie Estacado, a 21-year-old mob hitman, finds himself possessed by a malevolent supernatural force called The Darkness. The Darkness endows Jackie with incredible power but also holds him prisoner, bending him to its dark will. In the game’s most memorable scene, The Darkness forces Jackie to watch helplessly as his girlfriend Jenny is murdered by his Uncle Paulie’s goons. Thus begins Jackie’s quest for revenge, which will take him literally to Hell and back.

So, okay, maybe the setup is a bit too fantastic for your typical blues song, but beneath its horror and mafia trappings, The Darkness is a very human story about loss – loss of love, loss of control, loss of identity. And what are the blues about, if not loss?

———

I love it when videogames get setting right. Maybe the greatest strength of the medium is that it allows you to inhabit spaces, to make meaning from your interactions with them. The vast majority of games, particularly shooters, don’t make full use of the incredible potential of setting; the environments are only there to provide flavor or cover or the occasional puzzle as the player is spirited from one action sequence to the next. The freedom to slow down, to examine the surroundings and consider how they contribute to the theme and mood, is often cursory at best. Take this year’s sequel to The Darkness, which feels like an amusement park ride. At one point it literally puts you on rails in a rollercoaster. But the original Darkness encourages you to be much more contemplative between frenetic firefights. And that’s largely because of its striking vision of New York, which is as intimate and personal as the blues.

I love it when videogames get setting right. Maybe the greatest strength of the medium is that it allows you to inhabit spaces, to make meaning from your interactions with them. The vast majority of games, particularly shooters, don’t make full use of the incredible potential of setting; the environments are only there to provide flavor or cover or the occasional puzzle as the player is spirited from one action sequence to the next. The freedom to slow down, to examine the surroundings and consider how they contribute to the theme and mood, is often cursory at best. Take this year’s sequel to The Darkness, which feels like an amusement park ride. At one point it literally puts you on rails in a rollercoaster. But the original Darkness encourages you to be much more contemplative between frenetic firefights. And that’s largely because of its striking vision of New York, which is as intimate and personal as the blues.

———

Starbreeze’s version of the Big Apple is oddly reminiscent of the surreally empty NYC of 1979 cult movie The Warriors on a few levels:

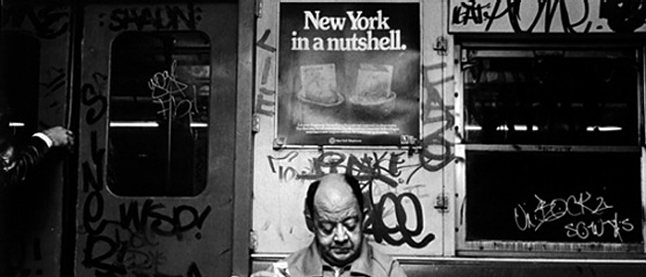

It’s small. There are no expansive vistas, no soaring skylines, none of the garish neon and blaring horns of Times Square. There are only a few areas you can access in The Darkness, fictionalized neighborhoods with names like Grinder’s Lane, and they’re all tiny maps, only covering a few blocks. Like The Warriors, The Darkness takes us from chunk to chunk of the city, with few (if any) wide establishing shots. You never see New York from a helicopter like you do in so many stories set there. The result in both cases is a thematically-perfect feeling of claustrophobia.

It’s dark. Obviously a game called The Darkness isn’t going to feature a bright color palette. And because Jackie’s Darkness powers wane in the light, creating shadows is a key mechanic. But the darkness works on a thematic level, too. In both the movie and the game, the city is shrouded in night until the very end, when both protagonists achieve a sort of redemption under the sunrise. And it’s quiet, too; in both game and film, short bouts of frenetic action punctuate an otherwise still atmosphere.

It’s dark. Obviously a game called The Darkness isn’t going to feature a bright color palette. And because Jackie’s Darkness powers wane in the light, creating shadows is a key mechanic. But the darkness works on a thematic level, too. In both the movie and the game, the city is shrouded in night until the very end, when both protagonists achieve a sort of redemption under the sunrise. And it’s quiet, too; in both game and film, short bouts of frenetic action punctuate an otherwise still atmosphere.

It’s empty. The city might never sleep, but it’s not exactly awake. Like the futuristic Detroit of last year’s Deus Ex: Human Revolution, NYC is largely a ghost town in the permanent twilight of The Darkness. The same is true in The Warriors, where the midnight streets are haunted only by rival gangs in bizarre costumes. The NPCs Jackie does encounter are crafted with a remarkable level of detail, though; there are custom animations used only once, like George playing the harmonica in Canal Street Station. If you reveal your Darkness powers in their presence, civilian NPCs will freak out and attack you or flee. And the voice acting and dialogue is so strong, even for ancillary characters, that the encounters you do have are always memorable. The overall effect is a thoroughly surreal atmosphere – which is entirely appropriate for a man possessed.

It’s hidden. This is not the Disneyfied New York of Spider-Man (or, some might say, of Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg). The action takes place in alleys and subways and tenement blocks, not against the grand backdrop of Manhattan skyscrapers. In both game and film, the protagonists are pursued by attackers through these lonely spaces, seeking safety in the shadows. But when it comes time to fight back, these forgotten places are their arenas.

———

My pal Rob Zacny says NYC in The Darkness is a “city of grief.” It’s setting as emotion, an inhabitable metaphor, where the player’s physical exploration of the space mirrors his exploration of the story’s theme.

It’s hard to argue with this idea. The game sells Jackie’s relationship with Jenny so well – you can, famously, sit on Jenny’s couch and watch the entirety of To Kill a Mockingbird on TV with her – that the sequence where she’s murdered is among the most affecting moments I’ve ever experienced in a game. On a superficial level, the game becomes about revenge after that event. As Rob says, though, it’s really a tour through Jackie’s grief, using the city as the medium. The first time you head to Jenny’s neighborhood after her death, Jackie delivers this monologue during the interstitial loading screen:

“Chinatown. You’re not here anymore. I’m trying to remember you. But all I get is the stupid shit. Like your wallpaper. The smell in your hallway. Even my mind is fighting me.”

“Chinatown. You’re not here anymore. I’m trying to remember you. But all I get is the stupid shit. Like your wallpaper. The smell in your hallway. Even my mind is fighting me.”

As in many of the interstitial monologues, Jackie’s using a place to talk about other people and about himself. The “stupid shit,” the small details of the spaces he inhabits, are exactly what makes the experience so poignant. It’s telling that Jackie seems to have a story for every area he visits. Starbreeze wants us to see New York through his eyes.

But if this is a tour of Jackie’s grief, it isn’t always guided. The act of choosing to explore is important here: Jackie’s emotional journey isn’t being force-fed to us. This freedom is crucial to the effectiveness of the story and theme.

You can see how this works in Chinatown after getting off the subway. In a completely optional sequence, if you go to Jenny’s apartment in Mulberry Alley and ring the doorbell, you’ll hear an echo of her voice and view a ghostly memory of your first encounter with her. Jenny’s excitement at moving into her new place, cramped and crummy as it is, becomes all the more sad in remembrance. The space you had formerly associated with happiness – a place of safety and innocence – is now a crushing reminder of your loss. As the memory fades, The Darkness issues a mocking chuckle at Jackie’s sorrow.

———

The thing I love most about The Darkness is that it invites you to pay attention. It doesn’t force you to seek out tiny details like a pixel-hunting adventure game, nor does it make you flit from setpiece to setpiece like a military shooter. Instead. it employs a remarkable attention to detail to encourage you to connect with its world.

Navigation is the best example. Where most games would have a HUD mini-map, The Darkness has you looking at city maps posted on street corners. Although the playable areas are small, it’s easy to get lost if you don’t slow down and notice the street signs, planning your route accordingly. One of my favorite flourishes is the info kiosk in the subway stations, which you can use to call a customer service representative for directions. Hearing the nasal drone of the rep – who sounds like an even more irritable Janine from Ghostbusters – recite instructions in her vaguely condescending tone is as bizarrely intimate an experience as the rest of the game.

Navigation is the best example. Where most games would have a HUD mini-map, The Darkness has you looking at city maps posted on street corners. Although the playable areas are small, it’s easy to get lost if you don’t slow down and notice the street signs, planning your route accordingly. One of my favorite flourishes is the info kiosk in the subway stations, which you can use to call a customer service representative for directions. Hearing the nasal drone of the rep – who sounds like an even more irritable Janine from Ghostbusters – recite instructions in her vaguely condescending tone is as bizarrely intimate an experience as the rest of the game.

The same ethic is applied to the environments. A documentary in the game’s bonus features reveals that Starbreeze hired prominent Swedish graffiti artists to create the tags on the walls. The graffiti itself often oozes personality: “FUCKING POSERS,” reads a script spray-painted over an artsy poster for the fictional musical “Dancing on Your Grave.” A stylized panda-creature adorns the wall of the Chinatown (“SHINERTOWN”) stop; outside, spray-painted on a locked shop door, is the phrase “CINCO DEDOS DESCUENTO” (“five finger discount”). Handmade flyers posted in subway stations advertise an “Intimacy and Relationship Course” and beg passersby to “Help us find Archie!” “Danger Zone,” proclaims one ad featuring three blonde bikini babes and a Nordic-looking stud, “Erotic Adventure Vacation Experience!”

Sound design works in the same way. Wandering the empty streets, you can hear police sirens off in the distance. Entering Pier 19, you’re greeted by the wailing of seagulls somewhere above the water. Down in the subway stations, intercoms periodically announce delays due to disabled trains. Walk up next to a shuttered door in the Lower East Side and you can hear a domestic dispute in progress, screams punctuated by breaking glass. And of course there are the TVs, whose multiple channels show a variety of real video: old cartoons, heavy metal music videos, a kung fu flick, Flash Gordon serials, even the Frank Sinatra movie, The Man With the Golden Arm.

My favorite aspect of this incredible attention to detail is that none of it matters from a gameplay perspective. Examining a poster or watching a cartoon does not earn you upgrade points. Even the collectibles you find are mechanically useless; they’re merely phone numbers you call to hear funny answering machine messages. The details are all there to help you inhabit this bizarre yet oddly believable world. That’s why they’re perfect: they make you forget this is a videogame.

———

In the Bible, Cities of Refuge were places of asylum, oases where people accused of manslaughter or murder could claim sanctuary. They were also places of atonement, where people who had killed others were expected to contemplate their guilt and make spiritual amends. Outside the Cities of Refuge, blood would have blood; no law of God or Man could protect a killer from vengeance. Inside, you might have a shot at redemption if you were not judged guilty of murder – if the death in question was ruled accidental or negligent and not intentional. But if the verdict was guilty, there could be no reprieve from the death penalty.

In the Bible, Cities of Refuge were places of asylum, oases where people accused of manslaughter or murder could claim sanctuary. They were also places of atonement, where people who had killed others were expected to contemplate their guilt and make spiritual amends. Outside the Cities of Refuge, blood would have blood; no law of God or Man could protect a killer from vengeance. Inside, you might have a shot at redemption if you were not judged guilty of murder – if the death in question was ruled accidental or negligent and not intentional. But if the verdict was guilty, there could be no reprieve from the death penalty.

Jackie is, of course, a murderer. We hear him tell us about guys he’s dropped in the water at Pier 19 wearing cement boots, about snitches he’s taken out. But we also use his powers to slaughter hundreds of enemies and eat their hearts. We use him to kill monsters and gangsters and cops and maybe civilians. We will eventually use him to confront and kill Uncle Paulie. Jackie will give in to The Darkness’s bloodlust, and The Darkness will claim his soul. He and the player both realize that he’s long past redemption.

As Tim Gearan sings:

But if you come out of the wilderness

A clean and humble man

Who’s to say you won’t come sliding back

To your wayward ways again?

Yet New York is a City of Refuge for Jackie. It’s a refuge in a literal sense from the insanity and horror of the WWI hellscapes The Darkness periodically transports him to. The city streets help ground him in, if not actual reality, at least something that’s more familiar. And the pervasive darkness, so oppressive to others, is Jackie’s sanctuary, even as Uncle Paulie’s goons hunt him down.

New York is also the player’s sanctuary. It’s a respite from the sensory bombardment and transparent systems of other games. And because we get to know Jackie through New York, because we understand him by understanding his environment, the city becomes a character, one that feels just as human as the people who inhabit it.

———

You can hear Tim Gearan’s “City of Refuge” in our soundtrack to A Week in the City. JPG sings the blues on Twitter @johnpetergrant.