Our Turf

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

I grew up, and still live in, an old industrial town called Kearny, New Jersey. It is approximately 11 miles and two rivers away from Manhattan. The most famous skyline in the world is clearly visible from my street corner.

This proximity meant I could enjoy the city without having to live there. During my childhood, my parents took me on frequent trips to museums (which I adored) and occasional trips to baseball games (which left me puzzled). Later, in high school, I would cut class in favor of taking the PATH train into the Village to explore the record stores and book shops and street vendors, or travel in at night with friends to catch punk rock shows at Coney Island High and Wetlands.

[pullquote] It seems to me that the filth lent NYC an authenticity that it now lacks.[/pullquote]

Back then, Manhattan was still dangerous. Alphabet City, Hell’s Kitchen, Harlem, Brooklyn, Coney Island – these were places of legendary peril. We mostly stuck to the Village. It was in the midst of its last gasp of Bohemian effervescence, but the ruthless tide of yuppie gentrification had left it mostly tamed. Besides the ever-present homeless people and vagrants, the worst danger we encountered was a middle-aged – bald and mustachioed – drug dealer who lurked near the intersection of 9th Street and 6th Avenue. He would intercept us every time we emerged from the train station, asking a ridiculous question like, “Hey guys, you know where I can find a leather wholesaler?” He would then ask, under his breath, if we were cops (seriously, dude?) and offer to sell us whatever drugs he had in little Ziploc baggies in his pockets. “I got shrooms and pills and the best weed: you boys can soar!”

We’d laugh and be content with walking.

———

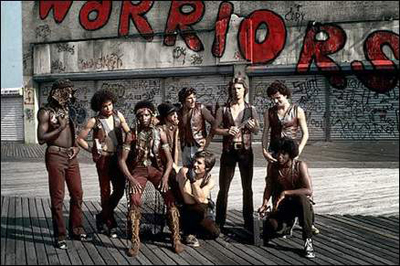

The Dinkins era was a far cry from the gritty ’70s, of course. The New York City of The Warriors, Taxi Driver, Assault on Precinct 13 and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is almost unimaginable now in a world where Park Slope is a traffic jam of affluent baby carriages and the Village is less a neighborhood than it is a university quad. There was a time, though, when New York was a blighted, crime-infested cesspool – and many people, including myself, have a fuzzy notion that it was better then.

It isn’t that getting mugged every night has any real appeal, or that the city as it stands now has nothing to offer, but rather, it seems to me that the filth lent it an authenticity that it now lacks. Poverty and rampant crime don’t leave a whole lot of room for bullshit. The rage it fueled, in punk rock and art and movies, seems honest, pure and unfiltered by today’s stuffy and distracted standards. It all seems infinitely more vital, more real.

There is a scene late in The Warriors that sums this up well. After having fought their way through every gang in the city, the exhausted Warriors ride the subway back to their home turf in Coney Island. Along the way, however, the train stops and some teenagers dressed in all their prom finery get on. How ridiculous they look, in their suits and corsages, next to the bloody, dirty, sweaty Warriors. What is more real than fighting for your survival?

There is a scene late in The Warriors that sums this up well. After having fought their way through every gang in the city, the exhausted Warriors ride the subway back to their home turf in Coney Island. Along the way, however, the train stops and some teenagers dressed in all their prom finery get on. How ridiculous they look, in their suits and corsages, next to the bloody, dirty, sweaty Warriors. What is more real than fighting for your survival?

If you want to love a city, you have to love it like you do a child – unconditionally, the good and bad together. It is easy to forget that the Warriors and their rivals are just high school kids, not much older than I was when I was exploring the Village. And, despite all the gentrification the city has gone through, there are still kids like them out there. They’re just harder to see. The bad is still there, too; New York is just better at hiding it, for now.

Rockstar’s 2005 videogame adaptation of The Warriors is a perfect extension of the themes of the movie, and is perhaps even more brutal. There is one brilliant moment, one of my favorite in all of videogames, when the Warriors square off against the Turnbull ACs, a skinhead gang from the Bronx. The fight goes down in a construction site and involves throwing bricks at the gang’s leader, an ornery blowhard named Birdy who is confined to a wheelchair and makes up for his disability with a handgun. All the while, FEAR’s blistering song “I Love Livin’ in the City,” with all its revelry for the fetid underbelly of city life, is playing in the background. Indeed, I do. In fact, I can’t think of anything better.

———

The city is more than just a grimy hellhole or an oasis for yuppie scum. It is also a bastion of culture, a civilizing force, a metaphor of the self and a monument to human achievement, not to mention the best place to go on a bender. Welcome to Unwinnable’s Week in the City, where we will explore the themes and realities of the metropolis, from the skyscrapers to the darkest alleyways.

Follow Stu Horvath’s experiences in New York (and Jersey) on Twitter at @StuHorvath.