Ruined by the Bell

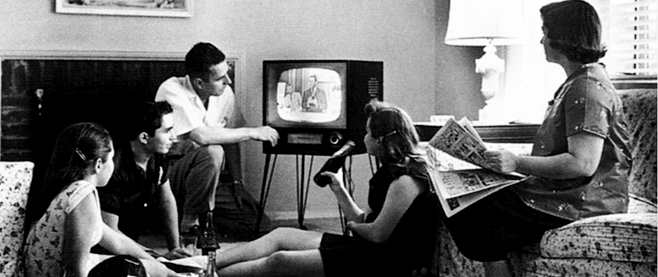

Television, perhaps more than any other medium, has the potential to define lives – particularly when it is being watched consistently by young, impressionable children and pre-teens with rapt and trusting curiosity. Nickelodeon, MTV and Saturday morning cartoons all helped to define a generation. Their unmistakable theme songs, their likable protagonists and vile villains and their over-the-top moral lessons were taken at face value by a score of young people who didn’t know to engage culture rather than merely consume it. Unfortunately, we would later apply what we had subconsciously learned.

For me, the most influential television show during my pre-teen years was Saved by the Bell. I watched it after school – usually two to three reruns a day. As a young kid with no real faith or philosophical direction to speak of, I took the show and its approach to life deathly seriously. Saved by the Bell didn’t discourage this treatment, either. Though it was transparently absurd to anyone over the age of 13, those awkward kids who were just beginning to think deeply and obsessively about relationships and themselves took its lessons at face value. The show dealt head-on (kind of) with issues like drug abuse, distant parents, divorce, drunk driving and other hot topics that gave kids a sense that they finally understood what all the fuss was about.

For me, the most influential television show during my pre-teen years was Saved by the Bell. I watched it after school – usually two to three reruns a day. As a young kid with no real faith or philosophical direction to speak of, I took the show and its approach to life deathly seriously. Saved by the Bell didn’t discourage this treatment, either. Though it was transparently absurd to anyone over the age of 13, those awkward kids who were just beginning to think deeply and obsessively about relationships and themselves took its lessons at face value. The show dealt head-on (kind of) with issues like drug abuse, distant parents, divorce, drunk driving and other hot topics that gave kids a sense that they finally understood what all the fuss was about.

For many, myself included, Saved by the Bell was the first introduction to incredibly complex and sober social issues. And 18 minutes after introducing those issues, they solve them. The show doesn’t blink in the face of any of them – even the multi-generational effects of slavery are solved in a single episode (Lisa (whose ancestors were slaves) allows Jesse (whose white ancestors were slave-traders) to take her on a mall shopping spree and all is forgiven). All of these socially conscious vignettes are deeply serious but are also weirdly crammed into the context of a high-school sitcom fantasy world. As a result, they are unavoidably simplistic and misleading.

Still, the singular focus of Saved by the Bell was on something that was a deeply felt need of preteens everywhere: what it meant to be cool. Over every other value, cool was esteemed and offered free rein over the world of Bayside High. Zack Morris, the literal epitome of “cool,” managed to remain at the top of the Bayside food chain for his entire academic career. He dated the hot girl, he got away with everything short of murder, and he did this with little to no real effort. His hijinks were far from ingenious, and involved such blunt force instruments as sabotage, dressing as women and bald-face lies. Oh, and the clever use of a giant mobile phone.

Zack served not only as the central protagonist in the series, but also as the primary communicator with the audience. He had a habit of breaking the fourth wall, explaining the insane inner workings of the high school to the audience. And, while all of the other characters maintain a cartoonish and unthinking stereotype, Zack exhibits his ability to indulge in shallow self-awareness. Essentially, Zack seems keenly aware of the startling fact of his existence: he lives in his own television show.

It is, after all, the only explanation for his overblown ego and flippant attitude toward the feelings of real human beings. Other than this, Zack plays his part dutifully, exhibiting a shallow repentance and deep insecurity whenever his hare-brained and self-aggrandizing plans go off the rails. Zack knows that these characters must ultimately accept him back into their good graces – otherwise the show won’t work. Still, his constant need for reassurance from what may be most shallow characters in existence demonstrates that Zack suffers from a deep, existential loneliness. Zack understands his role perfectly: the only human being in a world of cardboard cutouts, separated from mankind by a one-way mirror. He is starved for relationships with those who watch him. He communicates with them as if they are his best friends, but he can only find reciprocation within his carelessly crafted world. There, the girls worship him, nerds fear him and jocks revere him, but Zack can never be truly fulfilled. Zack is stuck in a white male escapist fantasy hell.

This speculation is not merely a thought-exercise. It has an immediate effect on the viewer, who feels an innate trust in Zack and, as mentioned before, tends to take the show seriously in its demonstration of everyday high school life. Young viewers see Zack’s sincerity with them as a show of solidarity and truth, and they devote themselves to careful study not only of Zack’s techniques, but his ethos.

This speculation is not merely a thought-exercise. It has an immediate effect on the viewer, who feels an innate trust in Zack and, as mentioned before, tends to take the show seriously in its demonstration of everyday high school life. Young viewers see Zack’s sincerity with them as a show of solidarity and truth, and they devote themselves to careful study not only of Zack’s techniques, but his ethos.

Of course, in writing “they” I am referring to myself, as well as the vague hope that this also includes someone else out there in the world. (Please God, let it be true.) In middle school I applied my Zackist worldview with fervor, expressing my attraction to girls with a misguided and inconsistent self-confidence, walking around with my thumbs in my belt loops, lying to get my way and laughing at those I dubbed uncool. The fortunate truth is that I couldn’t pull it off: very few girls took me seriously, my belt loops sagged and the “uncool” were actually quite cool. The joke was entirely on me. I was the nerd, desperate enough for acceptance that I would attempt to imitate a television personality. I was the one who wore my heart on my sleeve and made my affection for girls just a little too visible. I was the one who wore trapper-keeper designs on my shirts. In my school, that didn’t make me Zack Morris. It made me Screech. And in reality, being Screech meant more than being patronized and mocked – it meant being stuck with the emotional and psychological repercussions of those things, something Screech never seemed to struggle with.

Zack did his audience a disservice: he allowed us to believe we were one of him, when in actuality it was he who so desperately wanted to be one of us. He let us in on the inner workings of a fantasy world and lent it all the gravity of a Sorkinesque presidential drama. In the last episode of the series, “School Song,” Zack finds himself worried about his legacy. Though the show spins this as concern about what later Bayside High students will think of him, it’s clear that at this point Zack is concerned about the increasingly critical eye of his audience. He tells Screech, “You know, no one wants to be remembered as the school’s biggest goof-off. What I need to do is clear my name.”

Screech is, at least, honest: “The only way you could clear your name is to change it.” He’s right – Zack’s attempt to clear his own name involved brutally sabotaging his friends’ songwriting attempts so that his own would win a best school song contest and be sung for generations following. His friends discover this and embarrass him with an even more high-stakes moment of sabotage that results in public humiliation. Zack, with no other choice but to play along one last time, provides the show with a heartwarming moment in which the cast sings about their friendship. It is utterly unconvincing, and Zack goes down in history as the school’s biggest goof-off… at best.

Screech is, at least, honest: “The only way you could clear your name is to change it.” He’s right – Zack’s attempt to clear his own name involved brutally sabotaging his friends’ songwriting attempts so that his own would win a best school song contest and be sung for generations following. His friends discover this and embarrass him with an even more high-stakes moment of sabotage that results in public humiliation. Zack, with no other choice but to play along one last time, provides the show with a heartwarming moment in which the cast sings about their friendship. It is utterly unconvincing, and Zack goes down in history as the school’s biggest goof-off… at best.

But he never forgot Screech’s blunt advice. In his surreal appearance on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, Zack explains: “After school I became an actor. I had to change my name to Mark Paul Gosseler because there was already a Zack Morris in SAG.” But Zack is saving face – he had to change his name because, well… he had ruined his own. Just one more lie; and this time he deceived not Kelly or Slater or Screech, but his dear beloved audience.

But who are we kidding? Zack Morris has been lying to us all along.