Knightmare: Television for the Videogame Generation

I am running home.

I am nine years old and I am running, the frost cutting into my thin, pallid cheeks, the winter wind searing my ears raw, the sneering Scottish sun throwing its Vs at me from the red horizon. As my uncomfortable school shoes pinch, I imagine I am in the opening credits: I spring down the steps of my chosen shortcut, my books a shield on my arm, my schoolbag the knapsack of yore; the hood obscuring my view is that sacred helm. Knightmare is on in 10 minutes, and there is no way on earth I am missing the opening gambit.

I am still so overwhelmingly excited by that tune that my whole body tries to fold itself into the shape of a 9-year-old every time I hear it.

Knightmare was a British fantasy role-playing game show for children, heavily influenced by computer games and the ’80s Dungeons & Dragons culture that held socially inept imagination-dwellers like me in thrall. It aired at 4:30 p.m. on CITV, British channel three, between 1987 and 1994. It was groundbreaking in the way that it used blue screen technology – it allowed the makers to create different rooms in a ‘dungeon’ with computer-rendered backgrounds that I remember at the time were outrageously amazing. Now, they look like a gerbil on Ritalin could animate them.

[pullquote]Lord Fear was a total fuckmaster.[/pullquote]

Each episode, three young sorcerers of the pencil – known as ‘advisers’ – guided a blind warrior of the dungeon – the ‘dungeoneer’ – through the rooms by giving directions, solving puzzles and making decisions about what cruel fate the poor bin-headed friend would encounter next for the viewing public. A large and distinctive helmet made sure the dungeoneer* couldn’t see in front of them (too dangerous, you see), whilst the advisers watched the adventure happen through a ‘magic mirror’ (TV screen). Advisers could also cast spells by yelling ‘SPELLCASTING!’ and spelling out the secret word of choice (I still get the urge to say it at odd times – in a queue for coffee, on the Tube, during coitus). The tragic thing was most kids spelled the word wrong and failed the spell, whilst everyone at home wet themselves giggling.

There were three levels to brave, and teams could quest for a symbolic prize, sometimes the Cup, or the Shield – there was the Crown too. I sometimes wonder if today’s kids would be shocked that no monetary prize was offered at the end of the notoriously rock hard game show: you got a medal or trophy that was a mere tin token. Really, it was sheer prestige you played for. What could be more British than that? The idea that you played just for the brag. “Sure,” you’d say to your friends twenty years later in an Armani suit, cackling madly with cocaine dripping out of your nose and two blondes on your arms, “I’ll tell you the story about how I fucked that git Lord Fear for the Cup one more time!”

Of course, you probably didn’t. Lord Fear was a total fuckmaster.

———

The whole shenanigan of Knightmare was hosted by the illustrious dungeonmaster Treguard, played wonderfully by bearded legend Hugo Myatt. Myatt played Treguard with the glee of a slightly restrained and more enigmatic Alan Rickman: his grins and laments were dramatic and authoritative – not once did you suspect that he wasn’t a real wizard-type, or that after Knightmare stopped filming he was driving home in a battered Fiat cursing English drivers with the vehemence of a 13-year-old Xbox Live player (I don’t actually have evidence that he did that last part). His grandiose tone and  overblown consonants blasted several memorable phrases into your brain: “Welcome, stranger”, “Careful team, this is not a creature to be taken lightly”, and the classic “WARNING TEAM!”. Deaths were given the standard “OOOH, nasty.” Treguard was accompanied through the series by several assistants, one usually just as irritating as the last, who served as a kind of cheeky exposition foil. His sign-off was usually something related to “illusions” or “it’s an illusion” or “the only thing that isn’t an illusion is the adventure”. Or “we’ll be waiting for you,” or something about “the secrets of my lair” which is slightly more creepy.

overblown consonants blasted several memorable phrases into your brain: “Welcome, stranger”, “Careful team, this is not a creature to be taken lightly”, and the classic “WARNING TEAM!”. Deaths were given the standard “OOOH, nasty.” Treguard was accompanied through the series by several assistants, one usually just as irritating as the last, who served as a kind of cheeky exposition foil. His sign-off was usually something related to “illusions” or “it’s an illusion” or “the only thing that isn’t an illusion is the adventure”. Or “we’ll be waiting for you,” or something about “the secrets of my lair” which is slightly more creepy.

Throughout quests, the teams would encounter odd selections of items on tables, of which they would have to decide what to take (room in the Knightmare knapsack was limited). There was usually a key, a spyglass and some sort of food. Sometimes there were scrolls with spells or riddles on them. Sometimes a useless gold bar that the teams always picked up. Sometimes the item rooms were guarded by a monster or a talking wall (my personal favorite – a mesmerizing feat of computer graphics). If you looked into the spyglass, you could ‘spy’ on the opposition, usually Lord Fear, berating his minions for arsing up again or posturing his next scheme.

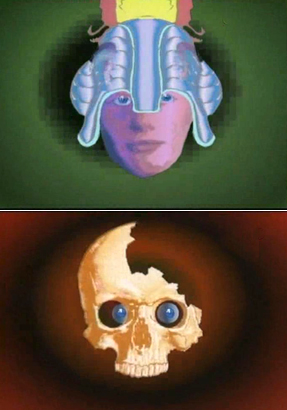

The energy or ‘life’ system between seasons 1-5 was the most memorable graphic on Knightmare. The dungeoneer’s health was indicated in the top left of the screen by the image of an armored face slowly being decimated, piece by piece, until it became a skull (the player reached the skull state, or death, if they hadn’t picked up any food, or had been attacked in some way). It was accompanied by a heartbeat sound. It instilled a sort of slow terror, one that embodied the fear I had about my own mortality, the one I was just coming to understand. I’d get very hungry when watching Knightmare; as if to stave off death one more day, I’d feel the need to eat a sandwich. But it was good for me. My young brain needed to think about these things: sandwiches and mortality…And their relationship to each other.

Knightmare had an ominous atmosphere that now, as an adult, seems pantomimesque, but the threats that Knightmare put in the players’ way seemed very real then. There were evil, lurking goblins constantly threatening to ambush the team; dragons that loomed over the screen booming in a deep voice; let us not forget the corridor of blades.

A 12-year-old on a conveyor belt of saws.

Every evening we’d sit, the garish sets and crude computer-generated graphics pressing themselves into our heads, impressing adventure into us, making us crave the interactive world videogames weren’t quite ready to deliver. Knightmare is responsible, along with Nintendo, for putting the fire of games inside me. It made me want to play role-playing games, board games, cooperative anything. It is responsible for my need to tell stories on paper, on radio, in the pub. It used to be responsible, my mother says, for the 9-year-old me’s actual nightmares about goblin horns echoing through forests.

———

Let me explain to you how in tune with my generation this television show was.

My most vivid memories of Knightmare are when it was in its highly refined seventh season. At that time, it was impossible for me to comprehend how my brain would cling onto every little aspect of that children’s television show, how important it would become to the development of my imagination, and how much it would engage my fellow freaks and geeks. Today I mentioned I was writing something about Knightmare on Twitter, and it was the first time in a long time that I’ve been bombarded with replies. I am still sifting through them. Nothing, it seems, stirs nostalgia in My People like mentioning the television landmark that is Knightmare. Here’s a selection of the fond memories I mined, naturally put up as if they were box quotes:

“The best bits were always the team yelling “LOOK OUT,” which was the most useless thing to shout at someone who can’t see.” – Paul Dean, Shut Up & Sit Down/Eurogamer

“I liked everything about Knightmare. My Knightmare tip is to NEVER pick up anything that looks useful, as it never is.” – Kieron Gillen, Marvel

“The health indicator (the rapidly decaying face graphic) – gruesome and efficient.” – Aaron Smithies, Snark and Fury

“We played Knightmare in my second year flat. My flatmate put a box on his head and I made him walk into a wall.” – @Vikkilovestea

“Beards like that just do not happen on children’s television anymore.” – Chris Thurston, PC Gamer

“The talking walls were excellent.” – Duncan Geere, Wired

Finally, Seb Patrick said, “I honestly think our generation has turned out better than the ones that followed specifically because we had Knightmare.”

This is true. That is a true statement.

———

Why did it speak to us so much? Because we were just becoming interested in what wonders technology could do for us, how it could bring to life things that had only lived in fantasy books before, things that were only just beginning to be explored by computer games.

Let’s look at its origins. The Knightmare began in 1985 in the mind of a Mr Tim Child. My friends, Tim Child is Our People, and not just because his name implies juvenility. I can tell, because at this time in 1985, the year I was born, Tim Child was a journalist who had an unnatural interest in 8-bit home computers when most people hadn’t even started to comprehend what one was yet. Let me remind you that this was a time when computers were instilled with a special witchcraft: a time when films like Weird Science treated computers as if they had the supernatural power to simulate and transmogrify a lithe and playful Kelly LeBrock into life, and only outcast nerds like Gary and Wyatt are the unwieldy wielders of this black art.

Let’s look at its origins. The Knightmare began in 1985 in the mind of a Mr Tim Child. My friends, Tim Child is Our People, and not just because his name implies juvenility. I can tell, because at this time in 1985, the year I was born, Tim Child was a journalist who had an unnatural interest in 8-bit home computers when most people hadn’t even started to comprehend what one was yet. Let me remind you that this was a time when computers were instilled with a special witchcraft: a time when films like Weird Science treated computers as if they had the supernatural power to simulate and transmogrify a lithe and playful Kelly LeBrock into life, and only outcast nerds like Gary and Wyatt are the unwieldy wielders of this black art.

When everything goes wrong, you get out a bat and smash the thing: who knows how the hell these mad things work? The normal person assumes that the computer is run behind the screen by a series of pretty fucked off imprisoned gnomes enduring a series of motivating shocks up the arse.

But Tim lived in the land of the Sinclair, Acorn and Commodore, and according to Child himself he saw Ultimate’s Atic Atac, and Hewson’s 48k interactive movie, Dragontorc, and thought that television should be reflecting a synthesis of its own slick production values together with the exciting possibilities of that fantasy-pixel torpor. Have a look at Atic Atac:

If you’ve seen Knightmare at all, you will easily recognize this game as being the forerunner of the television show. The rooms you negotiate, the little dude with the massive helmet (euphemism not intended), the health symbol (a roast chicken!) slowly altering. All the main ideas are there, but Child was unsatisfied with the primitive graphics, and Knightmare was born.

The best thing about Knightmare was that each adventure was truly different, and it kept the audience watching cliffhanger after cliffhanger. Tim Child said to Computer and Video Games magazine (issue 11.87), “A true role-playing adventure game should never play the same twice. A lot of adventure games are based on mapping or solving a dungeon or some other sort of maze. This just wasn’t good enough for a TV series. Once a good team worked out the correct route they would have cracked most of the problems. And worse still so would the viewers. Contestants won’t escape from the Knightmare dungeon that easily. For a start it’s irrational – it keeps shifting and changing. And the perils and puzzles change with it.”

The dungeon was irrational. This was something computer games couldn’t do yet: it adapted to its players, squirmed around with the dungeoneer inside its warped belly. It made for great television – but even better, it was teaching children that the world too was not rational, not a world where puzzles always made sense, that it was a place that adapted to suit itself. The dungeon was unequivocally about the unpredictability of people in certain situations, and the reaction of the show’s producers to the choices that were being made. In fact, Knightmare was totally and utterly unfair. Only eight teams won in eight seasons of, on average, 16 episodes a season. There are few fictions for children that teach that life is cruel: Knightmare helpfully lent a hand. Here are some of the painful ways dungeoneers bit the dust:

Not only was Knightmare born of a game, but it also inspired games too. In my online ‘research’, I came across one Kieron Gillen in the wilderness who said, “I dug the [Knightmare] Spectrum arcade/adventure, which strikes me as enormously ahead of its time.” Having never played it, I had a look. The stylings of the game seem detailed and attractive for the era, and there is a good sense of an oppressive, claustrophobic dungeon atmosphere in the graphic design. But it is extremely difficult to play – you can select words to have conversations and perform actions like dig and throw, which it takes a while to get used to, but the puzzles seem obscure. Crucially – it is a single player game, with no one to blame if your candle burns to the wick and you extinguish. You feel as isolated as the little knight you guide through the dungeon, and the small bearded Treguard** avatar that pops up every so often is little comfort.

This has something to tell us about the TV show Knightmare and how revolutionary it was: it was a cooperative computer game before its time. Not only did a player take part in a game environment, interacting directly with the actors, the objects and the doors and corridors, but players also collaborated from outside the game arena, making decisions, giving directions and providing advice over puzzles. Treguard and his helpers would provide hints and assistance. The game was a lesson in communication, problem solving, decisiveness, and how important those skills are. They could be improved throughout the game. Further still, the audience at home were participating by watching, perching on the edge of their seat when spells were being cast. Knightmare had a very low learning curve, and so anyone 12-14 could apply for the show and promptly send their helmed friend into the abyss: it was a new era of gaming for everyone, mass marketed and put on national television where everyone could see.

Since Knightmare went off air in 1994, gaming culture hasn’t had such a prominent, prime time slot on British television bar the legendary GamesMaster (Tuesdays at 6.30pm, ended 1998 with heavy heart). And yet, this kind of cooperative, mass spectated, almost crowd-sourced gaming model is something the gaming community are only just coming round to doing today – Starcraft GSL or any broadcast e-sport, Wil Wheaton’s board gaming show, the Yogscast gaming videos – especially the Minecraft ones. We love to participate and spectate and discuss, log in and take part. And the great thing is, with the internet we can all take part in one game of Minecraft or Terraria together. These are the legacies of our collective Knightmares.

The only difference is that you make your own dungeon in Minecraft.

I will leave you on that thought, and with my favourite Knightmare clip of all time, the wonderful and infamous ‘Simon, Sidestep To Your Left’.

SPELLCASTING! D-I-S-M-I-S-S

———

Notes:

* An aside. If you were chosen by your school friends to be the dungeoneer: I’m sorry. Your school friends remembered that, unsupervised, you were the kid who used to ram crayons up your nose shortly before devouring a rainbow-assorted selection and crying when your stomach felt like it would explode. What I am saying is that a teenage George W. Bush would be the ideal dungeoneer, and you are the person that most closely approximates him. Every dungeoneer enters a room and asks, “Where am I?” It is all one can do not to yell “YOU’RE IN A FUCKING BLUE SCREEN DUNGEON, MATE.”

**Such a legend was Treguard that he was later invited to do voicework on Peter Molyneux’s Black and White and Fable. (In Fable, his character was called ‘The Guildmaster’.)

———

You can find out more about Knightmare at the marvellous Knightmare Archive, run by fans of the show. You can do a SPELLCASTING at Cara on Twitter @CaraEllison.