Mastering Game Exhibits

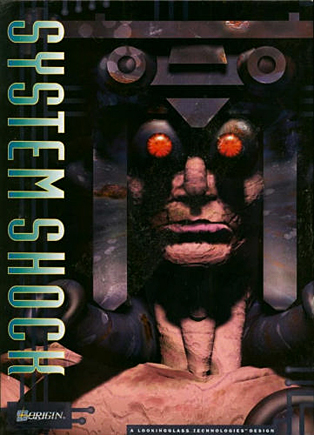

Last Wednesday night, in a gallery surrounded by fancily-dressed men and women, I played System Shock for the first time. I remember kind of smiling giddily to myself while I played it. System Shock. In a gallery space. If this wasn’t a broader cultural acceptance of videogames, then I don’t know what is.

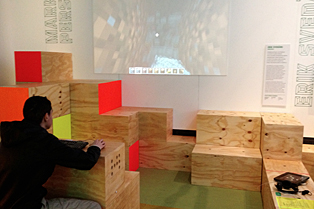

To be fair, I had drunk more than a little bit of beer, which might explain such grandiose musings. It was the launch party of the new Game Masters exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne. Truly, it is a terrific exhibition and apparently the largest that ACMI has ever housed. Dozens of machines and consoles are surrounded by concept art, original design documents and taped interviews of a whole spectrum of creators.

To be fair, I had drunk more than a little bit of beer, which might explain such grandiose musings. It was the launch party of the new Game Masters exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne. Truly, it is a terrific exhibition and apparently the largest that ACMI has ever housed. Dozens of machines and consoles are surrounded by concept art, original design documents and taped interviews of a whole spectrum of creators.

Visitors first walk in through a tight, loud arcade of shoulder-to-shoulder cabinets, each blaring a cacophony of bleeps and beeps. Donkey Kong, Robotron, Asteroid, Missile Command and many others are all present and accounted for in original cabinets.

Beyond a wall displaying perhaps every piece of gaming apparatus ever conceived, the space opens up into the main area of the exhibit, split into a series of sections, each based around the work of a specific developer. All four Metal Gear Solids are playable, side-by-side, in the Hideo Kojima corner. Shigeru Miyamoto inevitably takes up a whole wall with Mario and Zelda games. Fumito Ueda gets his own corner for Ico and Shadow of the Colossus. Yu Suzuki’s Shenmue is running on a Dreamcast, slightly concealed behind original Outrun and Virtua Fighter cabinets.

Further on, Peter Molyneux, Warren Spector, Will Wright and Tim Schafer each have a large section displaying their games, design documents and art. The original design document for Deus Ex is just sitting there! Further, past a humble little station for their early titles Amplitude and Frequency, Harmonix takes up a whole heap of floor space for Guitar Hero and Dance Central.

Then, finally, there is the indie room. Braid and Minecraft are present. Thatgamecompany’s trifecta of Flow, Flower and Journey sit side-by-side like animated postcards. iPads are spread throughout the room, showcasing the countless indie iOS successes. And, right at the end, just before you get the escalator out, is Fruit Ninja Kinect on your left and on your right, Vib Ribbon and Parappa the Rappa.

Then, finally, there is the indie room. Braid and Minecraft are present. Thatgamecompany’s trifecta of Flow, Flower and Journey sit side-by-side like animated postcards. iPads are spread throughout the room, showcasing the countless indie iOS successes. And, right at the end, just before you get the escalator out, is Fruit Ninja Kinect on your left and on your right, Vib Ribbon and Parappa the Rappa.

It is, undeniably, a great exhibition. It makes no attempt to be exhaustive in its representation of history’s game masters, choosing instead to take an incredibly in-depth look at a select few. Every element of the exhibition jammed into that space depicts another major milestone of the history, art and cultural significance of videogames.

As I left on that opening night, I still felt giddy that I had played System Shock, finally, for the first time ever, in a gallery dedicated to displaying culturally significant artifacts. Somehow, that seemed important.

———

To coincide with the launch of the Game Masters exhibition was a series of talks and panels the next afternoon. At a fascinating talk titled “The Collectors,” the challenges faced by those trying to preserve and conserve videogame’s cultural history were discussed. Warren Spector, developer of Deus Ex, Thief and many others, spoke about his own attempts to collect and preserve videogame history. He noted that, “I was floored when I saw System Shock playing downstairs. The devs themselves can’t get the game running, but you can go downstairs and play it. That is stunning!”

I returned to the exhibition that afternoon. The suits and dresses and red carpet were gone, and no one was filling my glass up with beer. I looked at the System Shock machine that I had played the previous day and realized that, truly, there is nothing I could tell you about System Shock that I could not have told you before I played it. I had played it, yes, but I had no idea of why this game was so seminal or significant. I had no idea what it meant. It just looked like another obscure old game with obscure old controls.

It is undeniably great that anyone can walk into ACMI and play System Shock. But is playing an old game enough? Especially if that game relies on a story or other systems that can’t possibly be fully explored in five minutes of play? What is it that is culturally significant about games? How do we share that? How do we preserve it?

It is undeniably great that anyone can walk into ACMI and play System Shock. But is playing an old game enough? Especially if that game relies on a story or other systems that can’t possibly be fully explored in five minutes of play? What is it that is culturally significant about games? How do we share that? How do we preserve it?

As videogame exhibitions become more and more ubiquitous in gallery spaces, and as (some) videogames become increasingly complex, these are the kinds of questions that inevitably arise. Some games are, generally speaking, simple and confined. If I play Asteroid or Missile Command in a gallery for five minutes, I might not master them, but I will “get” them. I will have had the chance to engage with every bit of the system, and I can go away musing over how they were – and still are – culturally significant. In fact, it is the arcade games that left the biggest impression on me after Game Masters. I learned so much about games I have only ever read about, and I was able to play each of them for long enough to continue thinking about them days later.

But you just can’t comprehend a game like Shadow of the Colossus, System Shock or Metal Gear Solid 4 in a 5-minute go in a gallery. It’s like trying to understand the significance of Moby Dick from reading a single page of it. To appreciate Shadow of the Colossus, you need to ride Agro across the desolate, agoraphobia-inducing landscape for minutes on end. You need to be dumbstruck by the sheer size of the Colossi. You need to struggle and fail to climb it and, eventually, you need to slay it and watch it die. Yet many of the exhibition visitors I see approach the Shadow of the Colossus machine don’t even see a colossus. They run around and jump for a few minutes, and walk away thinking they have played around with “just another platformer.”

It is not that these bigger games are more or less significant than the simpler arcade games, but that there is simply, quantitatively, more stuff that needs to be engaged with for the game to be understood and appreciated. Far more than can ever be experienced in a 5-minute stint, standing in a gallery space. How does an institution like ACMI or any art gallery or museum capture and communicate the cultural significance of such an experience? Is that something that can even be captured?

Australian game historian, curator and academic Helen Stuckey noted in the same panel as Spector that the question of just what gets preserved and presented of videogame cultural history comes down to several key debates of definition: are games text or performance? Do we record artifact or activity?

Stuckey went on to note that we’ve got the hardware and the software, but not the cultures. “You can preserve the code and let contemporary people play it, and that is great. But it is so hard to go back and understand why it was played and why it was important.”

Stuckey notes that this is why videogame historians collect walkthroughs, magazines and all the writing and stuff around the games in addition to the games themselves. “We want to collect and preserve fans’ memories and understandings.”

Stuckey notes that this is why videogame historians collect walkthroughs, magazines and all the writing and stuff around the games in addition to the games themselves. “We want to collect and preserve fans’ memories and understandings.”

Game Masters does a superb job of capturing the artifacts. They are sitting there. You can go up and poke them and press their buttons and look at them and, in a stilted sense, feel what they are like to play. But the activities are, largely, still inaccessible. How do you present a political coup in Eve Online in a gallery? Or that moment of either Portal or BioShock that was only significant in its context? How do you explain to me, someone who has never played System Shock, why this game mattered so much to the people who played it?

This is in no way a criticism of Game Masters or the commendable amount of work its organizers have done to pull it together. Game Masters has masterfully demonstrated how to place the corporeal games themselves in a gallery space in a meaningful and engaging way, and they have taken some crucial first steps in figuring out how to also present the ethereal experiences and meanings that surround them. If videogame culture and history is to be presented, preserved and remembered, capturing the fuller significance of these experiences seems to me like the next big challenge that the galleries have to surmount.

———

Unwinnable thanks Mark Serrels and Kotaku AU for the kind permission to use the images in this article.