Good Boy

A green carpet. Two loving parents, a house by a laboratory, a tiny tree in the front yard. A water boiler in the kitchen, a television in every room. Bright red footstool. Spotless floor. Overbearing silence. A premonition that they are gone.

These are the images of my arranged childhood.

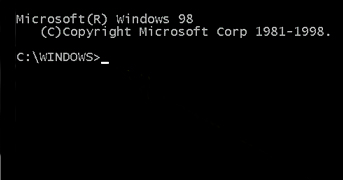

Steinway piano. Trophies on the mantle. Unsmiling photo of my grandfather. The past is filled with stereotypes; steaming bowls of white rice, the smell of incense, an interest in science and classical music and achievements; what’s one more? I spent the afternoon downloading Quake with a dial-up modem onto the personal computer my father built.

Steinway piano. Trophies on the mantle. Unsmiling photo of my grandfather. The past is filled with stereotypes; steaming bowls of white rice, the smell of incense, an interest in science and classical music and achievements; what’s one more? I spent the afternoon downloading Quake with a dial-up modem onto the personal computer my father built.

My father had taught me the MS-DOS commands, sitting me on an office chair where I craned my neck over his right arm. I’d watch his hands, which might have been bigger than my head, keying in the letters with the deliberation of an ox’s tail – CD to get our bearings, DIR to find what we needed, SETUP or INSTALL to release me. In these moments he was stuck in such deep concentration that I could only wait, with some nervousness, for him to move away from the screen. When I had the words in my memory then DOS became a prosthesis. I felt the system could recover my missing emotions line by line. Its burning white files, tumbling into my field of vision, had a purpose and a private logic, which I did not ever have.

This is the way I departed from my parents.

———

I felt it was above all important to play Quake, since it was a new thing: not a toy, but a totem of the future. This is what is happening, I thought, so I did it.

In the game’s predecessor Doom, you would shoot something dead and its remains would lay there forever in a kind of rigor mortis drawn in 2D pixels, an icon of the departed. But in Quake, you could spin in a circle around a 3D corpse and its limbs would spin around with you, dancing with your fingers. Even after you had killed everyone and everything in the castle, the game would still hold you close. It still knew you were there.

My parents would enter the room and ask, “Ryan, what are you doing?” And I would reply, “Nothing,” a half-truth, and they would leave me alone for a time. And I would have to expect their return, and to study hard, and to attend a college within driving distance, and to become a doctor like my father; these were the things that were happening. Quake was only the next happening that wouldn’t stop.

The videogame was no escape from myself, my guilt and lack of agency and programmatic way of trailing after the facts. Instead, Quake was just a vacuum. I would launch the program and it would suck the room dry, draining the green from the carpet and muting the sound. I would be left alone, thank God, with my thoughts. My first thought was that I knew nothing about the world beyond myself; my second was that I did not want to have control.

I should say that I became obsessed with the game, that I had catharsis in designing my own maps in Quake. But unlike my father, I never had the heart and nerve to build the painstaking world around me, preferring instead to be the implement. This is how I played Quake: I would push forward only a few steps at a time, resenting my own weight, even though my body in the computer had no mass and I was technically flying free.

I was still following in his footsteps. I had to lay the perfect path, because Quake was a world too open and unpredictable for a rational person to act freely, with intuition, with feeling. I covered up the rules of the game with more rules and I forgot the point of playing. If I lost too much health I would reload the game. If I wasted bullets I would reload the game. If the game tried anything I had not foreseen, I shut it off.

I was still following in his footsteps. I had to lay the perfect path, because Quake was a world too open and unpredictable for a rational person to act freely, with intuition, with feeling. I covered up the rules of the game with more rules and I forgot the point of playing. If I lost too much health I would reload the game. If I wasted bullets I would reload the game. If the game tried anything I had not foreseen, I shut it off.

In order to play the game, I had to change it. In the first few months of Quake‘s release there were mods that added weapons, took away gravity, handed you keys to a giant robot. The one I chose was Cujo – a command line that put a dog at my side. Cujo was rabid, apathetic to my input, independent. Cujo led me around corners like a seeing-eye dog and mauled whatever demons were there. The dog made its own decisions and followed its own path and so it appeared to be alive. Meanwhile, I saw the world in a dead stare, its blood and torchlight and infinite archways retreating into heaven.

In this airless space at the edge of the world, I had only to nudge Cujo into action, not unlike the way I wished, and still wish sometimes, to be given a nudge out of complacency.

———

The illusions of non-player characters complicated to the point that we could legitimately say we had “fallen” for Alyx Vance, Garrus Vakarian or a horse. They made the perfect motions and looked us in the eye and said what we wanted to hear. But each year we age, these creatures seem more dead than living. We notice their tenuous walk, as on a high wire; the way they numbly repeat themselves and react only to the right things in the right ways at the right times; their glassy eyes.

This brings up some difficult questions: Why do we care deeply about such a character, if her love for us is predetermined at birth? If one day this person can feel on her own, how are we supposed to trust that person? But shouldn’t we trust that she cares about us?

Ryan, what are you doing?

This week I have cleared my list. I have finished my work, paid my bills, acted responsibly, acted freely, acted for myself. No one needs to take care of me, I don’t think.

We’ve just returned from a cruise with my family. It’s a nice, neat world, where the fun is outlined on a daily printout, the waiter brings twice as much food as you ordered, the routes are mapped out and narrated and in the shade, and the views are always gorgeous. If I admit I enjoyed our return to hysterical sense, we might do it once a year.

[pullquote]I watch his lips moving up and down with a robotic flutter. His words are smeared with script ink.[/pullquote]

For now I’m thinking about the apocalypse. I’m playing Fallout 3 again, where the D.C. subway is blanketed in dust and radiation. I walk onto a freeway and look at nothing. I peel back corner after corner on the dead world, dozens and dozens of corners. This is the careening future Quake wanted me to see, but it lulls me inward with such loving silence. I proceed at my own pace and time, and my prodding uncovers not death, but memory. I open a cupboard and a plate clatters onto the floor. I feel guilty.

The moment resounds like the bomb had just exploded. This, too, feels like the future. It’s a future I think I understand. It’s a future of domesticity – of psychology and shrinks, not cyberpunks, graphics and geeks. A future of asking why, then and now, instead of wondering what is next.

I awake from a dream in the game and find my father staring at me. We are standing in some kind of lab, as if this were all a test. I watch his lips moving up and down with a robotic flutter. His words are smeared with script ink. Still I feel an urge to listen to him. I don’t want to miss any of his instructions. He has that glassy stare, but also my Chinese eyes.

Although in the course of the game I’ve understood that I am merely an outfit, several subsets of numbers, and a camera, I am unable to break down the body of my father. The face shimmers between his and my own.

We are running on brown hills. My father has to be somewhere and I am running after him. He follows his own path and opens the world to me. But I notice his stiffness of gait, that familiar way he repeats himself. This far behind him, where I can’t see my father’s face, he looks like any non-player character. But he also looks different.

If I look the other way, I won’t know where my father is going to be when I look back. So I keep him constantly in my sights, the crosshair resting on his back. My father is always running ahead, disappearing into a crowd, losing me and my mother on city streets. Sometimes he’ll run across the street and we’ll be separated by an onrush of traffic. Now there’s nothing between us but dead air. I seem to be falling continually away, still struggling to lift my armor.

If I look the other way, I won’t know where my father is going to be when I look back. So I keep him constantly in my sights, the crosshair resting on his back. My father is always running ahead, disappearing into a crowd, losing me and my mother on city streets. Sometimes he’ll run across the street and we’ll be separated by an onrush of traffic. Now there’s nothing between us but dead air. I seem to be falling continually away, still struggling to lift my armor.

When the creatures hurt him, I freeze time with the Vault-Tec Assisted Targeting System. I empty all of my bullets into them. I don’t check my resources or my health. I don’t know if my father can actually take care of himself, even though he is holding a gun. And then he runs out of bullets, and he puts up his fists, and he is surrounded by the natives. For all my power, I can’t tell him to run. And he dies.

I reload the game. I see my father running already beyond a hillside. We dispatch our enemies together. The only problem is that I can’t read his status. I just point and focus and refocus my sights on him, counting the seconds until we finally get to wherever we’re supposed to be going. My one desire is to catch up and find a way to give my father health. I’ve seen him take a lot of damage without flinching, but I don’t know if this is a sign that I should let him go.

And I don’t save my game, for fear of puncturing the illusion with a save screen. What I wish is to play out this drama – to believe that it is true, and that we do not need any help; that it will just work, that it will be free of bugs, free of failures, free of those unpredictable times that ruin things, free of the myopia that sees potent meanings float on by, and free of an early end, if not ever free of conflict. The final image of my arranged childhood, across the valley, is the figure of a man disappearing.

———

Ryan Kuo, AKA @twerkface, is the managing editor at Kill Screen and a fan of dubstep made in 2005.