GDC 2012: The Other Sides of Videogames

The annual Game Developers Conference is a hydra of many heads. You try to pin down just what GDC ‘is’ and one of the other heads lashes out at you from behind, reminding you that you haven’t really pinned it down at all.

Most obvious, there are the lectures – developers talking to their peers about one of countless facets of game development. But then there is also the press, circling the Moscone Center for a chance interview with this developer or that. There is the PR and marketing, hoping to to use the circling press to peddle next month’s games. There are the various expos – a little bit of E3’s consumerism to pepper GDC’s industry. There’s the middleware pushers: physics engines and front ends and font packs and online integration monetization tube holes. Then there’s the Steam/Rockstar/Blizzard/EA “We’re Now Hiring!” intern farmers, sifting through the crowded streets for desperate, gullible students.

It’s a videogame Mecca. Anything to do with the industry, market or art of videogames comes to the Moscone Center in San Francisco to nest once a year. Atop everything else, it’s a real-life reunion for a community usually separated by oceans.

But there’s another side of GDC, too. Another hydra head too distracted by something over there to ever make itself known to the outside world. It’s having a chance encounter in the press room. It’s sitting on the floor of a hallway to play a prototype of a game on a laptop. It’s at a spontaneous, unofficial press event in a hotel room. It’s watching a game projected onto a nightclub’s wall. It’s playing on an iPad pulled out at a pub. “Here’s a game I’ve been working on. Want to have a go?”

So here’s a shout-out to this underside of GDC. The games you see in passing. The games that might never see the light of day as purchasable items, and the games that don’t even want to. The games that matter no less than the ones EA books out an entire hotel for. Videogames are legion. Here are a few of them.

Hokra – Ramiro Corbetta and Nathan Tompkins

Projected on a club’s wall at both the Wild Rumpus and Kill Screen parties during the week, Hokra is a simple sports videogame of, essentially, 2-v-2 soccer. Two green squares face off two purple squares over possession of a black pixel, passing and bouncing it across the screen and trying to get it to each team’s respective corner to score. From a bare minimal visual and mechanical design comes an exhilarating and instantly accessible game. It’s like all the excitement of an entire soccer game crammed into three minutes.

Projected on a club’s wall at both the Wild Rumpus and Kill Screen parties during the week, Hokra is a simple sports videogame of, essentially, 2-v-2 soccer. Two green squares face off two purple squares over possession of a black pixel, passing and bouncing it across the screen and trying to get it to each team’s respective corner to score. From a bare minimal visual and mechanical design comes an exhilarating and instantly accessible game. It’s like all the excitement of an entire soccer game crammed into three minutes.

On each night, crowds would gather and cheer as each game always – always – came down to the last play. There is just enough reliance on chance for every game to be a fascinating spectator sport. So much so that I could not fathom this game working without a beer-fueled crowd looking on.

Planck – Shadegrown Games

Matthew (Wasteland) Burns is a great writer and a great game developer, having worked on a variety of AAA titles. On the side, he is part of an indie outfit going by the name of Shadegrown Games which, for a while now, has been working on Planck. When Matthew told me on the first night of GDC that he was carrying around the latest build of Planck on his laptop, I got more than a little bit excited.

The following day we sat down in one of the Moscone Center’s many public areas and I had a go. Planck is beautiful. Half Audiosurf, half Rez, Plank is a music-generating shooter less concerned with killing everything, sticking to a rhythm or perfectly replicating someone else’s song, and is more concerned with taking some sounds and beats and making them your own. You learn what sounds different objects will make when you shoot them, and you decide which ones to target to compose the track you want to hear. Unlike any other music game I have ever played, I found myself making intentional decisions as to what I would shoot just so things sounded like I wanted them to sound. It’s a transcendent, tranquil experience and one that I can’t wait for you to play.

Johann Sebastian Joust – Die Gute Fabrik

A videogame without a screen. The rules are simple: each player holds a PlayStation Move controller and if they move it too quickly, they are out. To win, you must try to slap other players’ controllers to knock them out while keeping your own controller steady and moving slowly. It’s like a strange kind of slow-motion kung fu. A mix of violence, underhand tactics, and defensive, sluggish reaction times. I did not participate in or view a single game of Joust that was not utterly hilarious. A favorite on the IGF Pavilion show floor and a nominee for two IGF awards, Joust is perhaps the first motion game where wearing the safety strap is actually crucial. When it’s released, it will be worth the admission fee of (expensive) Move controllers and (even more expensive) real-life friends.

Proteus – Ed Key and David Kanaga

Technically, I played Proteus before GDC, but I didn’t experience it before I watched it being played at the Wild Rumpus party. After consuming too much gin and too much loud karaoke, I retreated to a walled-off room at the back of the club, where Proteus was being projected onto a wall. The player sat in a comfortable-looking armchair, surrounded by cross-legged club-goers sitting on the floor, transfixed by the screen like children being read a story as the player chased a frog across an island.

Technically, I played Proteus before GDC, but I didn’t experience it before I watched it being played at the Wild Rumpus party. After consuming too much gin and too much loud karaoke, I retreated to a walled-off room at the back of the club, where Proteus was being projected onto a wall. The player sat in a comfortable-looking armchair, surrounded by cross-legged club-goers sitting on the floor, transfixed by the screen like children being read a story as the player chased a frog across an island.

Proteus is a hard game to describe. “Dear Esther mashed into Minecraft via Swords and Sworcery EP and held together with Boards of Canada” is about as specific as I can hope to get. You explore a highly abstract, pastel island and, well, do stuff. You explore. You look. You walk. It is beautiful on a laptop with earphones. Hidden in the back of a club at 2 a.m. it is something else. Something else entirely.

Mark of the Ninja – Klei Entertainment

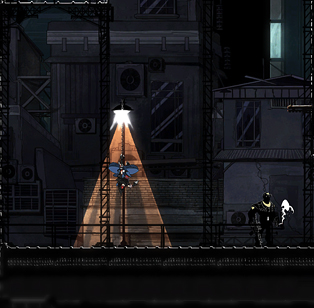

Klei Entertainment, makers of Shank, are now making a – dare I say it – wicked cool stealth sidescroller about ninjas. ‘Stealth sidescroller’ seems like such an obvious thing to be cool that I was actually surprised when I could think of no other game having done this (except, of course, Bonanza Brothers on the Sega Master System). The side-on view lets you fully appreciate just how slick this ninja is while he dangles from lamps and pounces on guards and lurks in shadows. You get to both watch and control. It’s a dual pleasure that the more traditional first- or third-person stealth game can’t quite convey in the same way.

Helping to write the game is no other than Chris Dahlen – Kill Screen cofounder, games journalist extraordinaire and all-round nice dude. After a videogame blogger dinner one night (that sounds so much sillier when you write it down), Chris, along with Klei’s Nels Anderson, took about a dozen of us to Chris’s hotel room, where we all took a turn with an early build of the game. There was no PR, no hushed whispers about what we can or can’t talk about, just a couple of really enthusiastic guys really excited to show a bunch of people this game they’ve been working on.

It’s early days, but thanks to a repurposed Shank engine, Mark of the Ninja already looks amazing and feels just as good. There are multiple paths to take, a variety of ways to silently (or not so silently) assassinate guards, and, most importantly, there are grappling hooks. This game is going to be amazing.

It’s early days, but thanks to a repurposed Shank engine, Mark of the Ninja already looks amazing and feels just as good. There are multiple paths to take, a variety of ways to silently (or not so silently) assassinate guards, and, most importantly, there are grappling hooks. This game is going to be amazing.

Waveform – Eden Industries

Technically, I didn’t play this game at GDC, but I did obtain it at GDC. While wondering around the IGF Pavilion, one eagle-eyed Ryan Vandendyck spied my media pass and came up to introduce himself. He gave me the spiel for his game, Waveform, and we traded business cards, just like I had done many times every day of the week. However, Vandendyck’s business card came with a USB drive attached to it. Genius! I have dozens of PR and indie emails from GDC I’ll never get around to opening. I’ll never get back to them. Not because I am intentionally ignoring them, but they will just get crushed under the flow of new mail into my inbox before I get a chance to even look at them. But this game, on its USB drive, is right here next to me. I already have it. I just need to plug it in and play.

Still, I didn’t get a chance to have a go of Waveform during GDC, but the moment I got off the plane in Melbourne, Australia, there was an email from Ryan waiting for me, reminding me about the game and linking to a YouTube trailer so I would know what I was missing out on if I didn’t play it.

So I played Waveform, and it was pretty fun. You drag a mouse cursor around the screen to control the amplitude and frequency of a wavelength that the avatar rides across, collecting things and avoiding things. It starts out simple enough but becomes deceptively tricky very quickly.

The game is good, but not nearly as impressive as Ryan Vandendyck’s commitment to the game and to get a random journalist to play it. He did not hang back behind an email and try to make an appointment. He approached me and thrust a USB drive into my hand then followed up on it when I still had not gotten around to playing it. And now, just by me writing about that, he is getting the press coverage he deserves. The game comes out on Steam on March 20, by the way.

———

So those are some of the other games of GDC. Not all of them. I could go on and on and on about the real-time rock-paper-scissors strategy game I had thrust at me by a developer at another party, the various iPhones pulled out by green-shirted volunteers to show me the latest builds of their student projects, the number of times I had to step over people in hallways as they got lost in laptop prototypes.

Some of these games you’ll get to play one day. Some of them you never will. Beyond the developer’s bedrooms and the occasional GDC party, some of them don’t even really exist.

So why tell you about them? Just to rub in how cool going to GDC is? Well, partially. But more so, to stress that this is what videogames are. From Battlefield 3 to Johann Sebastian Joust to Proteus projected on a nightclub wall. GDC isn’t the hydra. Videogames are. They come in all shapes and forms and, crucially, are played in all sorts of scenarios and environments. Be they commercially viable or not, be they played by two people or two million, videogames are a magical, varied, multi-headed thing that you can never really pin down.