An Academic History of Storytelling in Videogames

A couple of weeks ago, I learned of a website called Unemployed Professors. Essentially a higher-priced version of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, the site serves as a middleman between academics of questionable ethics and students who wish to hire them to ghostwrite their school papers. There was much debate on Twitter at the time as to whether the site was an elaborate joke, a brilliant commentary on higher education, an actual bunch of mercenaries in tweed jackets or some combination of all three. I immediately set out to find the truth.

I signed up and posted a job. While I had to play the part of a student, from the beginning I had every intention of running the results on Unwinnable. The subject of the paper? Why not see what these ruthless magisters could do with Unwinnable’s all-time most-read piece: Brian Daly’s “A Brief History of Storytelling in Videogames.” After a short bidding process, I hired Professor Rogue for the task. The two-page, double-spaced result was filed three days later, complete with footnotes (it was also in APA style, which we stripped out in favor of our house style). Is it as funny as BTD’s original comic? Will I get an A?

———

The use of coherent and user-manipulated narratives in videogames has increased significantly from the arcade era to the modern console era. This essay demonstrates, through case studies of 1978’s arcade-era Space Invaders, to 1987’s first-generation RPG, Police Quest, to 2006’s The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, that the user-adaptability and coherence of narratives has increased greatly over this time period. Subsequent to this chronological tracing of the evolution of narrative in videogames, the essay concludes by examining psychological literature demonstrating humanity’s preference to think and act through narratives. On the basis of this, the essay concludes by proposing that the increasing usage of user-generated and manipulated narratives in videogames is likely to increase the popularity of the medium, on the sole basis of narratives’ psychological benefits.

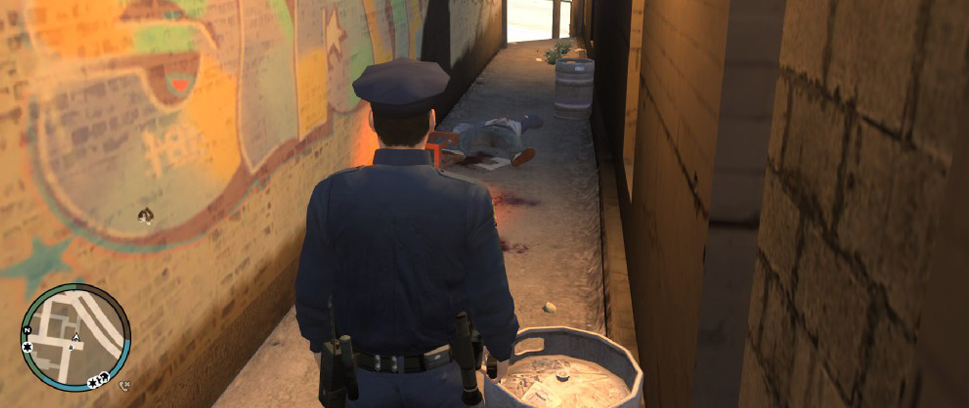

Thus beginning with the Arcade Era, specifically Space Invaders, we find that the narrative of a game is largely secondary to the action of its game play. In Space Invaders, the player, prior to actually playing, is given a brief and superficial overview of his mission, but is not told of the substantive components of the narrative, nor does the narrative follow him as he plays the game. Moving forward to Police Quest, released in 1987, the user is faced with a much more significant narration. As the game belonged to the first generation of computer RPG games, it told a story, in which the player became the protagonist. To win the game, the player thus had to complete the narrative, and finish the story, as it had been written by the game’s writers, by accomplishing a series of formulaic tasks. Moving forward to the current era, and 2006’s The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the use of narrative in video games has evolved dramatically. In Oblivion, the user controls the narrative, inasmuch as initial choices, made when constructing the player’s character, and then at salient plot points throughout the game, actually change the story line, and thus the narrative itself. The narrative of the RPG is no longer formulaic, but rather, an actual function of the player’s game play, choices and decisions. Simply put then, over time, we have witnessed not only a growing sophistication, as pertaining to the use of narratives in videogames, but also a greater player influence on the events and outcomes of a game.

Thus beginning with the Arcade Era, specifically Space Invaders, we find that the narrative of a game is largely secondary to the action of its game play. In Space Invaders, the player, prior to actually playing, is given a brief and superficial overview of his mission, but is not told of the substantive components of the narrative, nor does the narrative follow him as he plays the game. Moving forward to Police Quest, released in 1987, the user is faced with a much more significant narration. As the game belonged to the first generation of computer RPG games, it told a story, in which the player became the protagonist. To win the game, the player thus had to complete the narrative, and finish the story, as it had been written by the game’s writers, by accomplishing a series of formulaic tasks. Moving forward to the current era, and 2006’s The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the use of narrative in video games has evolved dramatically. In Oblivion, the user controls the narrative, inasmuch as initial choices, made when constructing the player’s character, and then at salient plot points throughout the game, actually change the story line, and thus the narrative itself. The narrative of the RPG is no longer formulaic, but rather, an actual function of the player’s game play, choices and decisions. Simply put then, over time, we have witnessed not only a growing sophistication, as pertaining to the use of narratives in videogames, but also a greater player influence on the events and outcomes of a game.

Moving forward to analysis of the utility of narratives, they provide a tangible benefit, with regards to the popularity and commercial reach of videogames, on the basis of the psychological literature that examines their functions. At the most basic level, Thorndyke found, through a study of reading comprehension exercises presented with varying degrees of plot-driven narrativity, that the more coherent a narrative’s plot, the more likely an individual is to both recall and understand the story.1 From a theoretical point of view, Robinson & Hawpe propose that narrative dominates cognition because it allows individuals to create a causal pattern out of discrete and sometimes disparate events, and to make use of conjecture so as to fill in the blanks where relevant information is lacking.2 Moving to clinical psychology, Murray thus proposes that the narrative approach to psychology, at base, flows from the premise that “human beings are natural storytellers and that the exchange of stories permeates our everyday social interaction.”3 On the basis of this then, it is logical to conclude that the increasing sophistication of narratives is likely to increase videogames’ market share, popularity and reach. If human beings are indeed natural storytellers, and if the stories that govern our games continue to evolve, new individuals might be drawn into the realm of gaming, and with this, the industry is likely to expand.

References

Murray, M. (1997). A Narrative Approach to Health Psychology: Background and Potential. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(1), 9-20.

Robinson, J. A., & Hawpe, L. (1986). Narrative Thinking as a Heuristic Process. In T. R. Sarbin (Ed.), Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct (pp. 111-125). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Thorndyke, P. W. (1977). Cognitive Structures in Comprehension and Memory of Narrative Discourse. Cognitive Psychology, 9(1), 77-110.

[1] (Thorndyke, 1977), pp. 81-85

[2] (Robinson & Hawpe, 1986), pp. 111-112.

[3] (Murray, 1997), p. 9.