Detours Through the Self (or: The Only Monster We Need)

Last night the season premier of the PBS retrospective series Pioneers of Television focused on science fiction, highlighting the works of Irwin Allen, Gene Roddenberry and Rod Serling. From camp to catharsis, these innovators of televised science fiction have walked a fence between formula and function. Should small-screen science fiction simply entertain or are these future visions the perfect vehicle for (veiled) social commentary? Such questions permeated a premier that was much more than a superficial retrospective of Lost in Space, Star Trek and The Twilight Zone. Despite the constraints of its own time slot, the hour-long program did an adequate job of presenting this conceptual fissure with a surprisingly dialectical veneer (if only accidentally).

Last night the season premier of the PBS retrospective series Pioneers of Television focused on science fiction, highlighting the works of Irwin Allen, Gene Roddenberry and Rod Serling. From camp to catharsis, these innovators of televised science fiction have walked a fence between formula and function. Should small-screen science fiction simply entertain or are these future visions the perfect vehicle for (veiled) social commentary? Such questions permeated a premier that was much more than a superficial retrospective of Lost in Space, Star Trek and The Twilight Zone. Despite the constraints of its own time slot, the hour-long program did an adequate job of presenting this conceptual fissure with a surprisingly dialectical veneer (if only accidentally).

It almost worked.

As chance has it, the dictates of chronology formed the perfect model by which to articulate the argument of entertainment versus enlightenment. Beginning with Irwin Allen’s 1964 series Lost in Space as its thesis, Pioneers of Television posits that televised science fiction served to entertain alone. Allen’s philosophy of “fast, simple, fun” ensured a budget-conscious product that guaranteed ratings while providing the requisite thrills – the perfect combination in the eyes of any self-respecting network executive. In lieu of controversy, its most “revolutionary” episode was entitled “The Great Vegetable Revolution,” pitting the Robinsons against cadre of vindictive produce. In direct competition with Batman, concerns over ratings found the show diluted with recycled monsters and thinning story lines.

But science fiction is all about the adventure, right?

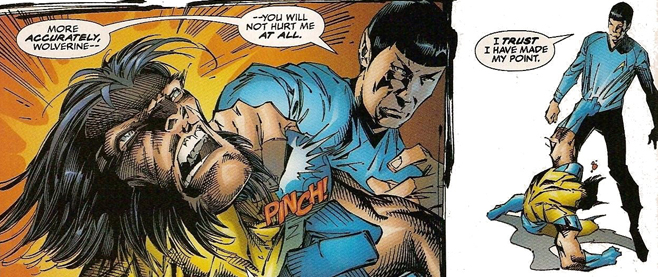

The CBS hierarchy shelved Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek, preferring instead to green light Lost in Space. Roddenberry managed to change their mind in 1966 (after a second pilot, no less), and with arguably the most important science fiction television program of all time he managed to inject every American household with more than just adventure – he forged a dialogue.

Star Trek is the result of the revelation that the best way to approach socio-psychologically sensitive subjects in socio-psychologically insensitive times is to “predict” the future. Not only was the show a series of socially conscious morality plays in which subjects from gender to nuclear proliferation were addressed, it turned the “race question” completely on its head. In the mid-1960’s, while Dr. Martin Luther King was spearheading the civil rights movement, an African American woman by the name of Nichelle Nichols portrayed the role of Lt. Uhura. In so many words, a black woman was the fourth in command. This role was so fundamentally important to the movement that King himself convinced her to rescind her retirement from the show after the first season. To provoke even more controversy, the episode “Plato’s Step-Children” featured TV’s first interracial kiss.

Such forward thinking came with a price. Through the lens of the simple, fast, fun formula the show was notoriously slow, and for all of its subtle brilliance, it lacked the base excitement that came with each episode of Lost in Space. It was too cerebral. Executives urged Roddenberry to write in more monsters, to which he of course refused. Star Trek, like its foil, lasted for three seasons.

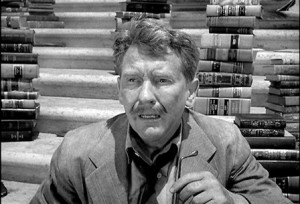

Although preceding the previously discussed programs, PBS was right to dedicate the final third of its program to The Twilight Zone, thus presenting a comfortable synthesis (third proposition) with which to reconcile the mutual contradiction between Lost in Space and Star Trek. Not only was Rod Serling a remarkable writer, he had the rare ability to keep an audience’s undivided attention – to have them believe that if even the slightest thread is pulled their entire existence will unravel – until he delivers that final blow of pure catharsis, leaving the viewer simultaneously exhilarated and self-conscious (and all in under thirty minutes). His Hitchcockian manipulation of suspense coupled with his short circuiting of reality – all the while dealing in universals – presented the perfect coupling of the compelling with the cerebral.

What drove Serling was his faith in the power of science fiction. He believed Star Trek to be a “creature of television rather than a creature of a pure literary form.” The Twilight Zone in its entirety is an anthology of short stories by way of the teleplay, each with a beginning, middle and end, demanding that the Self be read into every fortune telling napkin holder or pair of broken glasses.

What drove Serling was his faith in the power of science fiction. He believed Star Trek to be a “creature of television rather than a creature of a pure literary form.” The Twilight Zone in its entirety is an anthology of short stories by way of the teleplay, each with a beginning, middle and end, demanding that the Self be read into every fortune telling napkin holder or pair of broken glasses.

The virtue of science fiction is not limited to the medium through which it is presented. From the works of H.G. Wells to the revival of Dr. Who, the furthest of adventures without fail detour through the Self. The perceptive viewer will see passed the dry PBS template and recognize that Pioneers of Television: Science Fiction, if only by chance, manages to illustrate the evolution of sci-fi programming to its proper, reflective function.

~

You can help Peter come to terms with the 21st century by following him on Twitter @peterlangcrime.