The Man That Time Forgot: Hard-Boiled Wonderland at the End of the States

BY PETER LANG

[This will be the final installment of Peter Lang’s The Man That Time Forgot series. A culmination of his research will be forthcoming at an appropriate time, be it in the near or late future.]

It has been two weeks, Dear Readers, since your sleuth took to the road knowing not what Brunswick, Maine held in store for him. What secrets, clues and curiosities awaited in the untapped vein of American scholarship that is the Edward Page Mitchell archive at Bowdoin College? What disappointments lurked in the shadows of a potentially meaningless scrap-heap of ephemera? These and other questions filled the air with the static electricity of nervous excitement that is inextricably linked to such hard-boiled scholarship. As I sit comfortably at home preparing this account of my search for science fiction’s forgotten forefather that excitement has yet to fade.

It has been two weeks, Dear Readers, since your sleuth took to the road knowing not what Brunswick, Maine held in store for him. What secrets, clues and curiosities awaited in the untapped vein of American scholarship that is the Edward Page Mitchell archive at Bowdoin College? What disappointments lurked in the shadows of a potentially meaningless scrap-heap of ephemera? These and other questions filled the air with the static electricity of nervous excitement that is inextricably linked to such hard-boiled scholarship. As I sit comfortably at home preparing this account of my search for science fiction’s forgotten forefather that excitement has yet to fade.

Sunday, October 17

The stink of cigarettes clung to the air of my room at the Traveler’s Inn. I tried splashing water on my face to shake the lingering hypnosis of too long a drive alone and lit a smoke as I semi-coherently took in my passable lodging. Disoriented as I was, the anxiousness to explore an unfamiliar city was quick to take hold so I did what any self-respecting investigative man of letters would do after nearly seven hours on the road – I found the nearest bar. A sign pasted to the door reading “No Colors, No Weapons, No Drugs, No Attitudes” told me I had found the right place. Weathering the scrutinizing stares of day workers and the women who loved them, I took a seat and ordered a pint. The tired patrons soon forgot all about me. I could enjoy my beer in peace. Glass empty, I raised the collar of my pea coat and stepped out into the unforgiving cold of a Maine night. I was ready to go to work.

Monday, October 18

Bowdoin College is quietly tucked away in residential Brunswick. Deceivingly large, the school is spread across a wide green, its evolution evidenced by its architecture. Located on the third floor of the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library, the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives was the comfortable, glass enclosed reading room I had hoped for. Boxes pulled, it was time to find out what Mitchell left behind.

My fear of a first day dedicated to sorting a mess of documents was quickly abated with the first box. Mitchell’s correspondence had been neatly alphabetized. Thanking VALIS, I opened the first folder. Discoveries during this initial day yielded evidence of a man with a clear, recognizable literary voice, one who was sought after for advice and advancement in the world of letters. The most remarkable letter received by Mitchell [and the highlight of the day’s research] was addressed from Bloomfield, NJ. It appears Mitchell appealed to an individual for criticism, which is given both constructively and with due praise. In it Mitchell’s stories are described by the critic as “just queer enough to attract me.” Most named stories include his works in the realm of fantasy and the supernatural, yet The Balloon Tree and The Clock that Went Backward receive direct mention. One particularly striking line reads:

You seem to me to be E.P. Mitchell himself…with a [word illegible] of Hawthorne,

Poe…and Robert Lewis Stevenson-…all the while, as I said, you are yourself.

The critic’s language does not betray Mitchell to be an anonymous solicitor. Rather, it implies an educated assessment of a solid, identifiable literary voice – one that is distinctly Edward Page Mitchell. Thus ended the first day, and I had only scratched the surface.

Tuesday, October 19

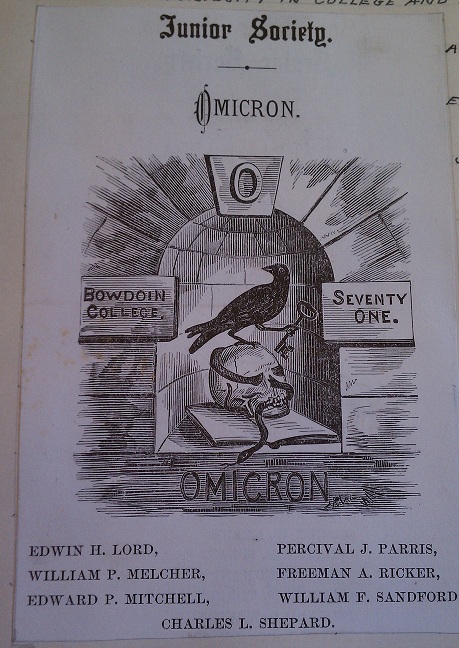

Day two was the shortest of the three. The first two hours were spent deciphering the last of the correspondence before moving on to the first of two scrapbooks, one detailing his time as a student of Bowdoin’s class of ’71, the other a compilation of letters pertaining solely to his writing. The Bowdoin book offered an in-depth glimpse into the maturation of the Mitchell mind. Contained in the ninety-something handwritten pages were lines such as

But the corpse got to its feet without assistance, and with a partly

affected limp, went forward to the president’s office to use the

accident as a pretext from [obtaining] a two day’s leave of absence

to go home to Bristol

which illustrate his innate creativity and unmistakable ability in describing such routine events as a friend’s accident in believably fantastic prose.

Also detailed throughout the memoir are sketches of friends and confidants who may have been the inspiration for characters in his fiction [Author’s note: this requires further investigation]. One individual, Professor Brackett, was conferred with during the writing of The Tachypomp. Mitchell states, “he assured of its originality and plausibility.” The 1874 story details the creation of a machine that can attain both perpetual motion and infinite speed. It is possible that Brackett is the archetype for Professor Rivarol, eccentric scientist of the above mentioned story.

Also detailed throughout the memoir are sketches of friends and confidants who may have been the inspiration for characters in his fiction [Author’s note: this requires further investigation]. One individual, Professor Brackett, was conferred with during the writing of The Tachypomp. Mitchell states, “he assured of its originality and plausibility.” The 1874 story details the creation of a machine that can attain both perpetual motion and infinite speed. It is possible that Brackett is the archetype for Professor Rivarol, eccentric scientist of the above mentioned story.

Finally, the confession “I was fond of the natural sciences and the manipulations of the chemical laboratory, and even of the dissecting table,” shows an interest in such scientific processes that would soon become a major theme in much of his fiction. This fondness is evident in much of Mitchell’s work, namely The Crystal Man, The Ablest Man in the World and The Professor’s Experiment to name but a few.

Wednesday, October 20 – Final Day

The third day was by far the longest and most intensive. Seven and a half eye-straining hours were spent poring over letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings and assorted biographical files. The last hour of work was dedicated to transcribing by hand Mitchell’s 1870 speech The Services of Superstition, a process which I am sure will contribute to my inevitable arthritis as much as reveal something of Mitchell’s philosophic and esoteric influences. My sleuthing paid off and I was able to land a fist on my desk and shout “pay dirt!”

Ranging from a biographical questionnaire, SUN inter-office letters, a story not collected in early Mitchell scholar Sam Moskowitz’s collection, and countless other pieces of evidence, a well-spring of information flowed through my tired fingers, my near-bleeding eyes missing nothing. Barely able to read, I made the last of my copies and celebrated over a pint of Guinness.

* * *

And there you have it, five days of my life spent in the trenches wading through dusty volumes and faded ink, crumbling newspapers and indecipherable script in hope of persuading the clock to go backward so that I might uncover at least some clue as to the man that time forgot.

The author wishes it to be known that although he is indeed kin to Edward Page Mitchell, all investigation into his influence on the world of modern science fiction has and will continue to be performed with strict academic and journalistic integrity. Bias in any direction will be influenced by facts alone. Any other approach would be simply irresponsible.