Pulp Culture

While recently browsing through delicious junk in an antique store in Essex, Massachusetts, I came across a book titled The Secret of Skeleton Island, by Bruce Campbell.

Now, I know what you are thinking, but the man that brought us Ash Williams of Evil Dead and Sam Axe of Burn Notice didn’t write it. However, I would be lying if I said the novelty of seeing his name on the spine of a 1949 mystery wasn’t the reason I bought the book. Bruce Campbell the writer is actually the collective pseudonym of Sam and Beryl Epstein, who wrote eighteen Ken Holt mysteries (of which Skeleton Island is the first) between 1949 and 1963.

They were similar to the mystery series produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Founded in 1905 by Edward Stratemeyer, the syndicate produced hundreds of books for dozens of series during the course of its existence (it was bought and absorbed by Simon and Schuster in 1987), but I only ever read the Hardy Boys and the occasional Nancy Drew. It wasn’t until series like the Ken Holt books popped onto my radar that I began to realize the odd and unique place Stratemeyer books, and those like them, hold in pulp culture.

Stratemeyer Syndicate was an early book packager, a company that put together books on an assembly line. Ideas were farmed out to outliners who created the basic framework of a novel, which was then passed to one or more ghostwriters who constructed the actual story. The book then went to an editor who could then commission additional re-writes from other scribes. Dozens of people would work on a single title.

Ghostwriting on such a scale wasn’t unheard of in the late 1800s and early 20th Century – some pulps in the 30s and 40s used a similar production system and Stratemeyer himself wrote several novels under Horatio Alger’s name after that author’s death. The syndicate, however, was the first company to actively court the juvenile market, a practice that has become commonplace for many modern book packagers (think Sweet Valley High).

And that’s where things get strange.

During their heyday in the 20s and 30s, the best selling pulps could move millions of copies. Despite pages filled with garish tales of horror, mystery, adventure and science fiction – what some today would call the very definition of puerile – the audience for the pulps was largely adult.

Stratemeyer, starting with the Hardy Boys in 1922, took formulaic pulp stories, stripped them of their most lurid content (though not, alas, their habit of employing crude racial stereotypes) and actively marketed them to children. I posit that these hokey mysteries with their light (and inevitably faux) supernatural elements and lack of real menace mark the beginning of a transition that changed genre fiction from a thing of universal interest to something marginalized as childish and lacking serious merit.

Which isn’t to say these kids’ books are bad – some boast an abundance of bizarre ideas.

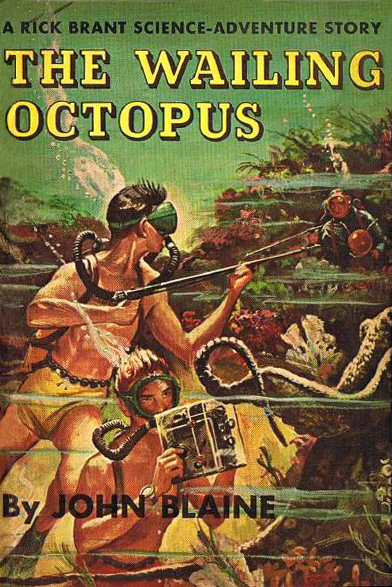

Take the Rick Brant ‘Electronic Adventures,’ which were written from 1947 until 1968 for Grosset & Dunlap. Rick and his buddy Scotty live on Spindrift Island, located improbably off the coast of New Jersey, where Rick’s father leads a team of scientists called the Spindrift Foundation. You can be sure that an island with a location named Pirate Field Rocket Launcher is the perfect place for science and shenanigans. Together with their friend Chahda, a boy from India, Rick and Scotty traveled the world in search of mystery and adventure through 24 books.

Wait a minute…where have I heard that before? A kid and his Indian sidekick having adventures all over the world with his super-scientist father – sounds an awful lot like Jonny Quest.

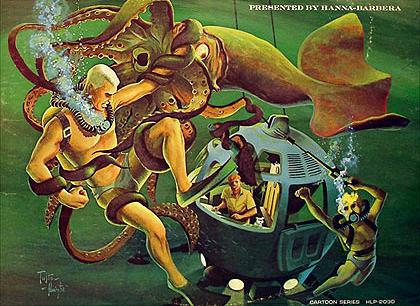

After the pulps began their decline during the paper shortages of World War II, the syndicate books carried on the pulp tradition, no matter how watered down, to the age of television. There they must have served as inspiration for classic Hanna-Barbera adventure cartoons like Jonny Quest in 1964 and Scooby-Doo in 1969. The parallels between Jonny Quest and Rick Brant are obvious. Meanwhile, every plot the Mystery Machine drove through involved some kind of criminal masquerading as a supernatural boogieman; pretty much the plot of every Hardy Boys book.

How much modern pulp did those cartoons inspire in turn? The list is seemingly endless: The Venture Brothers and Matt Fraction and Gabriel Ba’s comic book series Cassanova come immediately to mind for Jonny Quest while practically every story about investigating the supernatural since 1969 calls back to Scooby-Doo.

But while the line of descent from Doc Savage to Rick Brant to Jonny Quest to The Venture Brothers is clear, there are also signs of rot in the pulp family tree.

Many parents rightly found the use of racial stereotypes in Stratemeyer books objectionable (though these were written out of reprints beginning in the 60s) but libraries across the country took the argument to a level of absurdity when they charged that the books’ trite plotting made children intellectually lazy and rendered them unable to read real literature.

Similarly ridiculous arguments have haunted genre fiction ever since, perpetuating the notion that it was not only un-literate but also somehow intrinsically dangerous to children. Dr. Fredric Wertham nearly destroyed the entire comic book industry in the 50s by insisting there was a link between them and juvenile delinquency. Later, Saturday morning repeats of Jonny Quest came under similar scrutiny in the early 70s from Peggy Charren’s Action for Children’s Television organization for its use of realistic violence (admittedly, Ms. Charren is an avowed anti-censorship advocate with a very nuanced approach to protecting impressionable young minds and many admirable accomplishments to her credit. On the other hand, it is hard to argue that Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent, was anything less than zealous and dangerous).

Now here we are in a new century and genre fiction has finally shed its just-for-kids stigma and is embraced once again by fans of all ages. A new medium, videogames, has developed out of a narrative framework based almost entirely around pulp tropes.

And on November 2nd, the Supreme Court will decide whether the state of California can ban the sale of violent videogames to minors by giving them the same classification as sexually explicit materials.

The more things change…