The Incredible Light Shining Through Holy Frit

Not a lot of people know what their first big project is going to be. It tends to take you by surprise no matter what. But fewer still could’ve predicted the journey Tim Carey and Justin Monroe would venture into. The pair are a fascinating set of contrasts – Tim, a soft spoken, dark-haired artist specializing in classical mediums, and Justin, an enthusiastic, red-haired filmmaker. Yet they mesh well, both in conversation and at work. The two came together over a divine opportunity that neither could’ve anticipated: a debut documentary/grand scale stained glass art project for Resurrection United Methodist Church, as captured in the film Holy Frit. It’s a story of creativity, courage, and learning fast on their feet, which had me very excited to sit down with them to hear how all this came together.

“So I never wanted to make docs, man,” Justin says with a chuckle. “This was my first feature doc – my other projects have all been scripted narrative projects. I mean, I love documentaries! I just… I never expected to make one.” In fact, Justin had been trying to raise funds for a scripted project when, “This crazy story literally knocked on my front door. No joke. I moved right next door to Tim after doing a movie. So he tells me he’s an artist, a stained glass artist, and his company was bidding on the biggest project in the world.”

“Tim knew I was a filmmaker,” Justin gestures to Tim. “And he’s like, ‘We’re competing against 60 companies from around the world. And we need to look cool. Would you come film a little promo for us since you’re a filmmaker and make it stand out?’ And so I went down and met his boss and stepped into the studio, which is just incredible. I just – everything inside me said, ‘You’ve got to film something! This is amazing!’ And the more I heard doing the promo, the more I knew I was going to change my life because I’m going to take on this story. And they hadn’t even got the job yet! So that’s the first day to get the job. And then there’s this guy, Narcissus Quagliata. If Tim could find him, it’d be cool. From there, they let me start filming, just in case they got the job.” He grins wide, “And of course they did! And now I’m a documentarian!”

While Justin brought his more traditional scripted sensibilities to the world of documentaries, Tim’s most unconventional twist to artistry is, of all things, not growing up a starving artist. If anything, his family was and remains incredibly supportive of his endeavors. As he puts it, “I think the thing that was most helpful for me was that I just took things step by step. I just needed a little opening to get me from point A to point B. I was a science major, because that was what my family did, so that was an easy sort of jump, but then when I was in science, my grades were bad. It was clear I needed to find something else, but I didn’t want to be an artist because of the whole starving artist thing.”

That was, until it occurred to Tim, “Artistry can be a normal person’s job. Whether that was as a commercial artist, or a game developer – this was the mid-nineties when everything was taking off and animation was becoming digital. So I was like, okay, I’m not going to be the ‘artiste’ guy, I’m gonna be a commercial artist. So what happened was, instead of falling in love with the expressive nature of being an artist, I fell in love with the formal qualities of painting, and the technical aspects.” Art became a challenge, a puzzle, of a sort. That’s not to say his work lacks passion or emotion, but “I got into it from the point of view that “‘that’s really cool, how do you do that?’ That makes me feel something and I want to learn how to do whatever that is. So I followed that instinct all the way through, and I still do.”

It was that fascination to learn more, to experience bold artistic horizons, that unwittingly would lead to Tim’s work in Kansas. “As soon as I got into stained glass, I felt like I was in this sort of… a world of artists and craft that was almost frozen in time. And here I was, coming at it from this whole other point of view. So from day one, I was experimenting with glass, trying different types of painting, layering glass. Even though I was doing this job at this traditional company, I was always pushing for new ways to explore glass.”

Tim pauses a moment, reflecting, “And I dunno – maybe in my own way, I manifested it. Because I was looking to do new things. I was looking to shoehorn my own sensibilities into this traditional art form; which really when I say that it was steeped in this kind of… this malaise? A hundred years ago, it was fresh and vibrant. It was great artists who were doing outstanding work. Layering glass and creating these amazing melted. Drapery glasses and the best painters in the world were in glass. So I was looking to them and then looking at my background and going, ‘Let’s bring that back.’ And then, and over the course of doing some really cool things in traditional stained glass, we were found by this place in Kansas who just happened to have this job that allowed me to continue to explore new things.” He smiles politely, a bit of mirth at how at the time, he had no idea the task ahead.

“And I didn’t know that it was going to lead exactly to where it led, but I knew that if we were going to get this job? We had to do something different. We had to set ourselves apart from these other, big, contemporary studios who were doing things in Europe that were very avant garde. So we had to push it, and that felt like it was precisely in my wheelhouse to try doing that.” It was, as the saying goes, right place, right time. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t tremendous amounts of work. Even with the guiding hand of Narcissus, Tim and Justin’s respective teams were faced with a litany of challenges captured in vivid detail. Though the cameras were an adjustment at first, with a three year commitment, eventually they became second nature.

That isn’t to say there wasn’t pressure, both externally given the amount of eyes on such a monumental stained glass window, but also internally from the more experienced hands guiding Tim and Justin. “One of my favorite parts,” Justin recalls, “was one of the sides where I’m sitting there, and I’m watching a movie moment happen. The magic shows up. There’s that moment at the kiln early on where Tim takes his first crack at making a figure and they open up the kiln and it’s not right.”

“Then Tim says, ‘Look – as much pressure as there is on this project, it’s not a referendum on my life. If we eff this up, it’s not like I’m gonna die, you know; it doesn’t end all things.’ But Narcissus is like ‘No man. You don’t get it. If this sucks, it’s gonna suck for 500 years. These people are gonna have to look at something that sucks. So you better bring everything to this. You better pretend like your life depends on it.’ And it all came together organically, it just happened. And so that to me was so powerful because Tim’s real perspective at that time was verbalizing itself and Narcissus real perspective as the older master was verbalizing itself. They clashed and grew from there. I got to watch it over and over, but also I got to see the beauty that formed between their relationship and the tenderness that happened. It was both a friendship and Tim going through a metamorphosis in real time.”

Rather than having to do all the sort of prep work he’d normally be faced with, like drafting a script, Justin instead could witness the story unfold in real time. “So I love that process. I knew that the money would have to come on the back end, but nothing was stopping me getting it in the can. And so I tend to overshoot, overfilm a lot. Because why not? It’s digital. And so I thought, The way I want this movie to go, based on my sensibilities as a narrative filmmaker, I want to do this like a narrative film, but a real narrative film, real life.”

He grins wide. “How often do you get to see a human being transition before your eyes? Like you don’t really see it like that without the benefit of hindsight like a documentary can offer. And there were so many beautiful moments. That was a key one. These really emotionally intimate moments, and I’d embed myself like I wasn’t there. It felt so special. It felt… reverent! Or when Tim admitted he was afraid he wouldn’t meet the deadline. And Narcissus tells me, after having seen it, he’s like ‘I had no clue that you were even there that day.’ And it was like that a lot.” In total, Justin would film over 1,150 hours, trimming the final documentary down repeatedly with his editing partner, Ryan Fritzche, who had worked with him on several commercial projects prior, as well as helping fundraise while co-editing the film online.

“And, it helped to have the perfect foil in Narcissus,” Tim adds, “He’s the maestro, the artiste, takes his work very seriously. So he would get into these modes where he’s waxing poetic. And I just had to break the silence and get, like when he’s talking about, just getting intimate with the material,” Tim chuckles. “And I got to play around with him and make a little joke and start making out with the glass. And he gave me so many opportunities where he would just tee up these very serious moments and give me a chance to just cut to the fun of it all and loosen up the whole crowd.” They both laugh, remembering those days warmly.

“And then,” Tim continues, “ultimately, he started loosening up. We began a great sort of play back and forth with each other. I knew that I had one chance to do something that I would probably never get a chance to do again. I think what also helped me was that I had a really supportive family, my outstanding wife. I knew that she wanted the same thing for me. So I guess my advice I would give people is: surround yourselves with people who support you and have your back. If you’ve got people in your life who are gonna bolster you and hold down the fort at home, that really helps. And we had three young kids. I got very lucky, marrying a partner who was really supportive of what I was doing no matter what.”

“I would say the same,” Justin heartily agrees, “My amazing family who support my obsessions and are fine with me working for long periods on the different projects. What do you call that? That truly is luck, right? I think it is. There’s something about it. That’s not to say that you don’t have a responsibility to be there for your family. Of course you do. But there’s something about meeting someone on the way in life, as opposed to trying to fit somebody into a new direction you’re going. They’re coming along with you, they’re going to bring what they bring and man, I don’t know, it’s just… you gotta be true to yourself, but you also need to know when to stop and be with the people you love.”

That isn’t to say looking back on the early days of the endeavor is always easy for Tim. “I did spend a lot of time angry and looking back on it… I wish in retrospect that I’d handled it better. So this is advice I wish I’d had: be more patient with your anger and allow it to pass instead of reacting so quickly. I did a lot of reacting in the heat of the moment. And it pissed people off. And I think when you’re doing something really intensely, one of the hardest things to do is internalize something that’s bothering you and then go to bed on it and come back the next day. And I think when it comes to such major stress, you have to learn to be quiet and learn to think a little bit more before you speak.”

“And I’ve always been somebody who speaks before I think. In big situations like that, you could screw the whole thing up. And thankfully we didn’t,” Tim says with a sigh of relief. “I was nervous about it too because, you do have this responsibility as an artist to do something that is going to be received well by the community and, you want to give them what they want and you want to also be accurate, [as] a lot of what we’re doing had to do with the Bible.” As fate would have it, both Tim and Justin are religious as well.

Tim continues, “Being a Christian myself, I also wanted to be true to my beliefs and not do something that I felt wasn’t in line with the Scriptures and what the Bible talks about, but ultimately? What really helps as a commission artist is that it’s really not about what I want. It’s about what they want. And so I’ve gotten used to, over the years, being able to just compartmentalize and say, okay. Who are these people? What are they about? What do they care about? What matters to them as Methodists? Like I’m a Lutheran, we have minor differences in our theology, and what is it that they want, what’s going to speak to their community, and that’s ultimately what you want.”

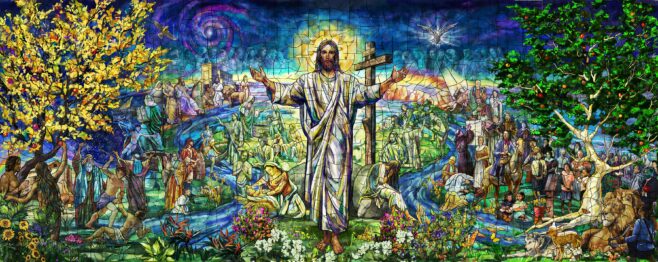

“And so I listened and I gave my opinion when I could. We went back and forth a lot. There was never animosity, there was like… the lion and the lamb. Except the Scripture says it’s a wolf with the lamb. And the pastor said, ‘Okay, you’re right. Let’s put the wolf with the lamb. We’ll put the lion in there too, because that’s in Revelations.’ So we did get to have a fun dialogue. I think it’s a healthy expression for their community who has a very powerful theology, and an intense desire to see these stories captured, this imagery. And I get to do it as an artist, so it’s a privilege, really. Then I went on to the next thing, which is an Egyptian Coptic church, where they have things that they want and the way they like to see it. So I’ve gotten used to being able to bounce between these different formats and interpretations.”

Justin leans in to add, “I wanted to add one small thing because for me as a filmmaker, which was so cool about the spiritual aspect is that Tim? He was a Christian when we got started, but he was pretty new to the faith at that time. That was so cool for me to watch a person, like, kind of… forgive himself and find his way? As a human and a believer, I found it so compelling. Tim was very honest and open. He just wore his heart out on a sleeve – like you said, just saying everything that he was feeling which as a documentarian is amazing, but including his spiritual walk, so to speak.”

“And he would say, ‘I don’t really know how to talk about this stuff. I don’t feel comfortable. I don’t feel confident to even know what I’m talking about.’ That was so beautiful, man,” Justin exchanges a smile with Tim as he continues, “because I think we’re always that way as humans. We don’t really have anything figured out, especially when it comes to spirituality. And I just found it really compelling to see a person go through the process as a human, as opposed to someone telling you some principles and rules, right?”

As for what to call the documentary, a number of ideas were tossed around, culminating in the realization about the two most persistent parts of the process. On one hand, for such a heavenly project, boy howdy was there plenty of swearing over the hurdles and challenges. And the other, a conveniently named raw material.

“At its heart, the doc is equally an exploration of the reverent and the irreverent,” Justine explains. “I loved what was happening, the profane and the profound and I tried to come up with a million names. It took me probably two years into the process as we were getting ready to submit to our first festivals. I was laying in bed one night, late, just thinking: “What is this movie? The Reverend, the Irreverent. Alright, the Reverend is holy. Right? Holy. And Irreverent. Curse words, right? Shit, fuck, whatever.’ So I went, ‘Wait a second, hold on. Holy Shit. Tim said that a billion trillion times from making this thing. Because, oh my God, holy shit, it’s such a big task.”

Obviously Holy “Shit” wouldn’t apply, but if there was one thing they were surrounded by, it was frit. Frit is the end product of grinding up glass, commonly used for stained glass projects like this. “And the holy frit was what made this possible,” Justin concludes, “It was used for a holy purpose, and wholly responsible for this being possible.”

The pair continue to work together to this day, with their current project being Vitreonics, which means “Glass” and serves as a platform for classes, inspiration, and deep dives into the glass art world, readily available online. As Tim puts it, “We capture the same kind of flavor that Justin captured in the film. In shorter form and medium form things. We’ve got YouTube going, social media, and Justin’s exploring some TV ideas. We’re trying to continue to push this medium to help people to see and find the beauty in glass art.”

———

Holy Frit is available for rent on all major video platforms.

———

With over ten of writing years in the industry, Elijah’s your guy for all things strange, obscure, and spooky in gaming. When not writing articles here or elsewhere, he’s tinkering away at indie games and fiction of his own.