Out of Reach, Out of Mind

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #179. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

The death of Game Informer wasn’t necessarily shocking so much as it was anxiety-inducing for me. Especially from the standpoint of a game critic who’s very aware of how volatile the physical media of games are. Indeed, a medium that is also subject to unstable or inconsistent preservation methods, institutions and organizational infrastructures. What galls me and practically everyone else reacting to or affected by Game Informer’s shuttering is that GameStop didn’t even value its treasure trove of knowledge and cultural appreciation of games enough to at least allow the site to remain an archive. This is not just an insult to all the staff of Game Informer who have put their heart and soul into the work they created for this magazine, only to be left with next to no portfolio (other than what physical issues they own). At 33 years, the magazine was one of the longest-running game publications in the United States. This move is a baffling one that underscores how disposable games and their cultural relevance are viewed by corporations. An ironic state of affairs given that said relevance is the currency that allows execs to cash out.

I believe that many of us don’t fully comprehend yet how important the concept of “out of sight, out of mind” is for games as a medium. The medium is strangely similar in some ways to other mediums like dance and theater, in that it centers ephemeral actions as expression. Various historical projects over the years have grappled and continue to grapple with the way that preservation of games is not just about the hardware and software but about preserving the interactive context of games. Games are commercial objects, yes, but only in those moments where players purchase them and their attendant platforms as products. The full ludic experience is only truly preserved in a narrow band. It happens when the feedback loop between organic bodies interfacing with technology is preserved. Irrespective to whether that sense is via tactility, affect or both. When you strictly define games as a commercial product, as GameStop does, you devalue the prominent place games and their rhetoric now have in our current zeitgeist.

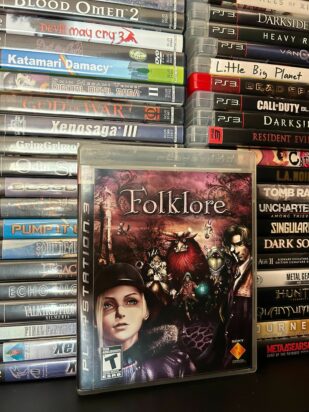

We’ve incorporated this rhetoric, for better and worse, into our everyday lexicon and design (i.e., “He has a cheat code because of X privilege”). We interact with gamified systems at work, with store reward programs. Our health, perception and memory can be influenced by gamified self-care apps and some games like UnearthU by Kara Stone comment on this. I’ve been exploring memory and games at length because I find it fascinating how deep the disconnect between games as physical objects and games as interactive representational media goes. Games take a lot of resources to make, including intangible ones like time, and if you’re like my immediate family and I, they can take up a lot of space too. I keep mostly every physical game I buy, for more reasons than one. But in recent years, having learned how important the decentralization of archiving efforts for media like games has become, I’ve become even more vigilant to maintain this collection (within reason of course, I’m not a hoarder). Now that game magazines like Game Informer are disappearing, I believe I’ll be treating some of my old gaming magazines the same. Or at least considering donating them to gaming history projects like the Video Game History Foundation.

Once during a podcast I was invited to speak on several years back, I voiced my skepticism of the future of games and streaming them. Xbox Game Pass hadn’t quite taken off yet in the way it has now, so at the time I compared my hypothetical experience of streaming games to how I stream Netflix. This was in hindsight a silly and reaching comparison, as I’m perhaps one of the least-invested consumers of TV content of any sort. It takes me years to try out shows that people I know and trust recommend highly, I hate sitting passively watching content for long stretches of time and I tend to only return relatively more often to my comfort shows. Games I have an entirely different relationship with, albeit sometimes a fraught one. They are a constant in my life and I play them almost every day, sometimes for inspiration and other times to ground myself. Past me would be shocked at the fact that I’ve already completed close to twenty or so games via Xbox Game Pass. Within less than a year of owning an Xbox at that. But you know what people preach about hindsight, right?

We live in a time awash in information, especially digital information. As far back as 2018 Mark Graham, the director of the Wayback Machine, commented that the Internet Archive adds four petabytes (equaling four million gigabytes) of data per year. He also jokingly referred to the main unit of measurement for the physical media they preserve as a “shipping container” because they receive that amount of material biweekly. Perhaps sheer scale and availability is what keeps us feeling (falsely) secure about the state of games preservation. This principle goes for both for games themselves and media about games. But it’s dangerous to remain unbothered about the permanence or constancy of games and their associated physical media.

What do I mean by this? Well, firstly, games are paradoxically objects containing experiences that do not necessarily exist in a stable sense when they’re out of sight and hearing. I’m still ruminating on Square Enix’s admission that some original source code for their classics might be lost. Secondly, the corruption of data storage over time a.k.a. bit rot is a thing. Thirdly, what games share with TV streaming services is that corporations have much more control over how we can access and, in some cases, perceive this media as well. This is the case despite the convenience and accessibility of streaming options like Game Pass. In this way I agree with critics like Richard Brody and Ted Kutina, who argue that while we don’t want to hoard physical media, we should think about how private curation can be a defiant act of decentralizing public archiving efforts.

Anthropologist and former sleight-of-hand magician David Abram popularized one of my favorite terms about perception in his book The Spell of the Sensuous – “more than human world”. He discusses the history of the philosophy of perception and language and their interrelation. At one point in an early chapter, he posits that the more of the natural world we lose to climate change conditions, the more language (both verbal and nonverbal) we lose. Language is an embodied thing produced from our sensorial interrelationship with the world. Therefore, to lose environments and entities within those environments doesn’t just spell distress for our ecosystem but for our communication. I wonder if there’s not a similar sort of linguistic or perceptual loss when games media is lost. Since games center action and our perception of action within various systems, would that mean we’re potentially losing our knowledge of taking action. What about games that deconstruct toxic systems of power? Or games that show us a way to process an emotional state, whether positive or negative? We might perhaps lose some of the unique ways we’ve perceived our bodies in space.

I don’t mean to sound alarmist, but games are one of the mediums that help a lot of us effectively express not just ourselves in terms of identity but our embodied experiences. Experiences which are within a matrix of systems that influence our daily, even our moment-to-moment actions and interactions. We should consider what we lose other than games or magazines as marketable products.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.