Intergenerational Design

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #175. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

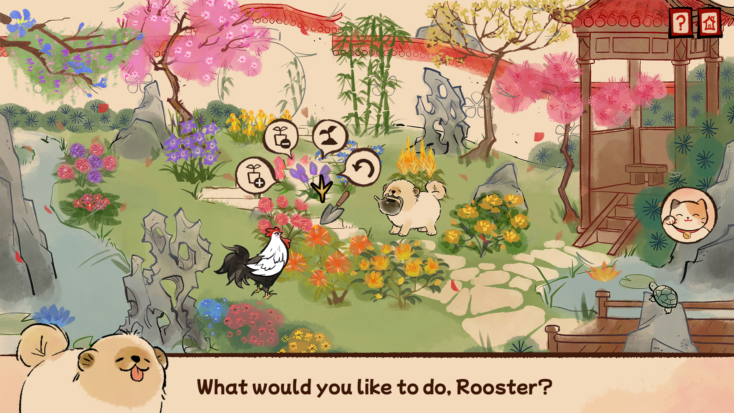

Rooster is an all-ages point-and-click puzzle adventure game by Sticky Brain Studios, a Toronto-based developer. The game seeks to celebrate Chinese history and culture in a unique way. Showcasing painterly graphics that evoke traditional watercolors and calligraphy, Rooster is a narrative-driven collection of twelve themed minigames. I’m excited to see the continuing trend of games mixing analog and digital media styles with their graphics (a la titles like Dordogne and Pentiment). The developer has also made one of Rooster’s core design pillars accessibility, which is heartening. In my experience, games that claim to be inclusive of a broad audience of players often forget about (or even ignore) disabled players or players with a chronic injury or illness.

The game is about the Rooster of the Chinese zodiac who has been sent back to ancient times by Dragon to relearn traditions and mend broken bridges with other fellow animals of the zodiac. This is the trickster-like protagonist’s punishment for ruining the festivities of the Chinese Lunar New Year’s feast with his rude manners and disrespect of others. When Sticky Brain’s creators reached out to me about covering their game, what I was intrigued by is how food is featured in its mechanics as a throughline for expressing Chinese history and culture.

Food and its representation and potential as a game mechanic, whether narrative or technical, is an affinity of mine. Food is, in my opinion, a subject that is never neutral. Even in strictly casual games like Cooking Mama and Candy Crush, food is an effortless and often on-the-nose signifier of a player’s consumption of gameplay. Rooster is a casual game too, but even with its early GDC demo, which I had the privilege of playing, it resists the rigid categorization of the previously mentioned casual classics. Although the controls are simple and the narrative a perfect framing for teaching players about Chinese history and culture, that is not the aim of the game.

Food unites many other common human experiences as well, such as survival, pleasure (not just sensual, but contentment), change, language (both verbal and non-verbal) and memory. Nina Mingya Powles explores this last aspect eloquently in Tiny Moons, her memoir of eating and immersing herself in the Shanghai half of her biracial heritage. When we revisit recipes we grew up with, we often find ourselves craving not just the physical experience of the food but the exact temporal experience of the memories attached to that food as well.

I was pleasantly surprised when, in a brief yet insightful Q&A with the creators of Rooster, they were keen to mention that they were not developing the title as an edutainment piece. According to the thoughts shared by Sasha Boersma (co-founder and producer), Deborah Chanston (writer/narrative designer) and Connie Choi (creative lead), Rooster “the game is not designed with anything educational in mind. It’s being designed for all ages.” And this sentiment aligns with my playthrough of the early demo – although there is an emphasis on gleaning facts of Chinese culture through lore points contained on interactive scrolls throughout the first level, finding these scrolls isn’t necessarily the goal of the level.

Although this early build did have some technical issues with triggering the next part of the narrative where Rooster must build a gift basket of cooking ingredients for Rat, it was difficult to tell if the trigger was linked to interacting with the scrolls. Your ultimate goal is to make amends for your transgressions of some Chinese traditions and interpersonal relations. This brought to mind recent Independent Game Festival award-winner Venba and its unapologetic authenticity in expressing the story of an intergenerational story about Indian immigrants throughout ’80s and early noughties Canada.

In a recent talk titled “Lore Don’t Tell” given at this year’s GDC Abhi, the creator of Venba, asserts that players should be encouraged to naturally observe and discover aspects of a culture that may be new to them via lore. Lore, unlike the more explicit narrative design of a game, can be potentially missed for those not seeking it but is infused throughout a game’s atmosphere and felt more organically by players. Abhi laced his game with countless references to Indian history and culture, some so niche that only people growing up in a similar generation and from a similar region to Abhi’s birth country might catch.

For instance, the scene where the father, Paavalan, reveals the result of the putu recipe Venba and Kavin cooked together is based off of a famous scene from an Indian film. There are also family mementos around Venba’s house which communicate culture in an ambient way, such as posters and collaged family photos. In Abhi’s opinion, the key to authenticity without pandering to a Western or international audience unfamiliar with a featured culture is to focus on representation over representativeness.

This is what the design of Rooster seems to be striving for as well, which I commend it for. There’s been a lot of fruitful discussion in recent years of how narratives centering non-Eurocentric or Western cultures need not be crafted for those audiences. Foreign cultures don’t have to be pressed into touristic service for those unfamiliar with them. Abhi’s advocating for lore imparting a sense of culture is in line with the opinions of writer-scholars like Elaine Castillo (whose brilliant and enlightening How to Read Now posits that Western and Eurocentric pandering undermines decolonization efforts) and Matthew Salesses (whose Craft in the Real World gets at how even at the workshop level of storytelling, the global north dominates and dictates form and representation). Jericho Brown has explored similar ground to Salesses, but from an African American and diaspora perspective in How We Do It as well.

There are two of the twelve mini games included in the demo, one a hidden item game associated with Rooster’s gift basket for Rat and the other a shape-matching game where Rooster is helping Snake keep a toddler safe from the many potential incidents that can take place at a market during a street festival. Both of these minigames are charming and are centered around food and family, as part of Rooster’s teaching moment in being sent to the past is to follow alongside Little Dove’s family. You also receive gifts in return from your fellow zodiac animals; some sticky tree sap from Rat and a lantern from Snake. I’m unsure as of yet what these items will be for, but I like that the player is not rewarded with points (though points do feature during the minigames as progress markers).

While these minigames did illustrate some important morals for Rooster, like putting others’ needs before his own and selflessness, I struggled a bit with how expository the dialogue after these games were. I wasn’t expecting the fable-like aspects of this tale to be so apparent, since the minigames within the overall framing of the tale already felt demonstrative enough to me. There’s a nice balance of narrative design and popular cozy gameplay with these two minigames, so to have the moral be told to me afterwards felt…not redundant, but close. At once, I found myself wanting to linger on the loading screens which featured philosophical quotes, yet found the loading times so whip fast (not necessarily a drawback in of itself) that I would never quite catch the gist of them.

However, I had to remind myself that this game is meant to be all-ages. Something that both very young players, kids ten and up and their parents could play, apart or together. And there’s something to be said for the classic feel of this game. As an older player, who grew up with several ’80s-’90’s public school computer lab titles like Number Munchers, Mixed Up Mother Goose, Mario Teaches Typing and others, Rooster’s simple mechanics and its inventive narrative framing resonated with me. Another discussion that arose out of my asking if the game was meant to be edutainment was learning that several of the Sticky Brain Studios team have a background in education games.

“[U]s as company founders, you know, collectively have decades of experience developing educational games for Canadian broadcasters, education companies, government bodies and [not-for-profits],” Boersma explained, noting that what they wanted to carry over from previous experiences in such development was a respect for the intelligence of their younger audience. Boersma’s co-founder Ted Brunt also led the children’s interactive departments for Canadian public broadcasters for well over a decade. “[W]e think that they’re capable of more.” Like me, Boersma grew up on ’80’s learning games, specifically The Learning Company classics like Reader Rabbit and Rocky’s Boots. Chanston added “I actually market myself as a person who specializes in preschool educational TV” when it comes to the writing side of Sticky Brain’s development.

Choi, who is in charge of the visual design of Rooster mentioned of the painterly graphics inspired by Chinese paintings and calligraphy that the process was organic. “It just happens to be the visual medium for that. And so, while it borrows a lot from that…we just want to pick a very different art style that other people may not have seen.” The three women also left me with a poignant thought to ponder: with their past lives likely influencing the mechanics of their current project, how might the next generation of game developers be influenced by the educational games they might have grown up with?

We often forget that despite all the technical aspects of game design, human involvement makes the process vibrant and organic. Despite it being an early build demo, playing and talking about Rooster was a delightful reminder of that.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.