Grief and Grace Along Route Zero

It’s August 2022. Central Montana. We’re leaving.

I’d settled here years ago, a transplant from Chicago seemingly destined to work odd restaurant and retail jobs for eternity, aimless and unaware after dropping out mere credits shy of a degree at the local university. My wife and I met while I was working one of these jobs – a video rental store, of all places. Though establishments like this started failing over a decade ago, this small mountain town held onto their niceties, unmoved like the vast ranges that surrounded it. Some, less empathetic to a culture rooted in staking your claim, would say “stuck.”

Then, the town became unstuck. Decades worth of advancement attacked it in an instant. For whatever reason, our home was invaded by people we didn’t know. It was the Yellowstone viewers with starry-eyed dreams of fulfilling their cowboy fantasies; it was the rich investors who saw new potential in something “untapped;” it was money coming to a place where money had never been as important as the sweat on your brow.

We saw the town we’d fallen in love with and in sour. Whoever could afford to stay was bitter. They were angry that their friends and family had been priced out in favor of people who were not giving back to their economy. They were petrified that they – fourth and fifth generation Montanans – would be next. For the first time, the sentiment of “this town is nothing like it used to be,” became reality, instead of some curmudgeonly phrase. The video rental store finally closed its doors. We saw our rent climb until it had doubled, and then we watched it amass further.

So we left. Then we buried the horses.

I came to Kentucky Route Zero not during its seven year rollout, but after my departure from Montana. After being driven from my own community, I took refuge in this narrative paragon, of characters brutalized by economic conditions beyond their control or comprehension. Driven into the literal shadows by the forces that invaded their community with promise of a richer life, all the while obfuscating the fact that this richer life was for them alone. I felt recognized.

I also felt rage. The pain of losing the life I’d been building was mirrored on my screen. I think of Ezra, a boy torn from his home by a bank’s eviction. I think of the empty houses I saw on my street, soon to be listed on Airbnb. I think about the family that was living there before, and if their son also had a bird named Julien. Route Zero had clawed its way from the Southeast to bear its concrete teeth in my former abode, seventeen hundred miles away.

Except, this is a fundamental misunderstanding of what the Zero is. It isn’t the harsh repercussions that industrialization has on a community. The Zero is the community left in its wake. The Zero is for the misplaced, for the survivors. As Conway makes his delivery to 5 Dogwood Drive, he forms bonds with all kinds of people: a TV repairwoman, android musicians, and little Ezra. He encounters poor souls cast aside by the corporation that scorched this land. He finds community. If I had felt the Zero within myself, it wasn’t rage. It was a burgeoning commonwealth.

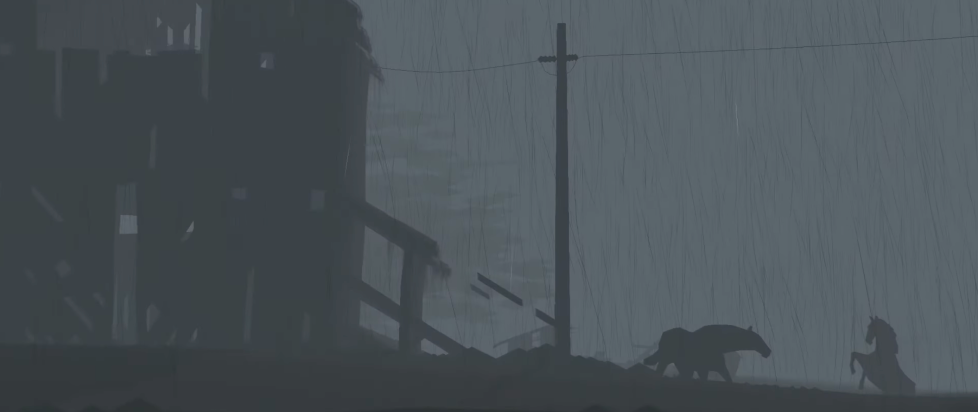

In the game’s fourth interlude, Un Pueblo de Nada, we see the final broadcast of a community TV station, WEVP-TV. The name of the interlude translates to “a town of nothing”, and how fitting that this town’s residents are, to the Consolidated Power Company that forced them there, nothing. When a storm floods the town during this broadcast, the figurative Pueblo de Nada truly becomes its namesake. Everything is lost in the waters.

Except, of course, for the people. The community. The characters we’ve followed throughout the game meet the survivors of greed and flood, and a new community is formed as the town recovers. They take the time to grieve their losses, including the local farm’s nearby horses that fell victim to the waters, the barn that offered them shelter becoming their tomb. They decide what their future holds – whether their path is to stay in this town and rebuild, or move on. They find 5 Dogwood Drive.

“Then we buried the horses.”

A twice-made refugee sings a parting hymnal as the horses sit in the newly formed grave – “I’m Going That Way”. Within churches this hymn marks the hope of heaven, and perhaps to the people living just on the outskirts of The Zero, it holds a similar message; perhaps here it holds a meaning we’ve seen elsewhere in the game: This is the way things are, and all we can do is keep moving. The path we walk will lead us, if not to heaven, then to an unknown distant trail that’s just the same trail we’ve been on already. As the first verse draws to a close, shadowy figures apparate into view to say farewell to the horses. They seem not literal ghosts of the deceased, but the souls of those who can relate to the passing of time and culture along the Zero. They join in the hymn, and the game comes to a close. It’s a beautiful moment.

As my life continues, I think of this scene often. It offers a comfort to the mountain town I left behind, a reminder that I’m not alone. As the souls come to put the horses to rest, they come to help carry me. These souls could be the people I said goodbye to, or the people who left before me, or both. They’re still here, alongside me. It’s not a weight I carry. It’s a community.

This summer past, my wife and I lost our child. There are no words to describe the grief that accompanies something like this. The emotion tears into you. We grieved, and we grieved, and still we grieve.

How do you get through something like this?

You bury the horses.

The loss will always be there. The community you have will too. It’s the people who have been through it themselves, and it’s the people who love you.

Together, you bury the horses.

———

Perry Gottschalk is a Colorado-based writer, thinking about games and the way they make us feel. For more feelings, follow @gottsdamn on Twitter.