Finding Time in a Dying World

It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that it feels like the world is collapsing. For Alma, the protagonist of Unsighted, the collapse of her world is measured in seconds.

I unfortunately have a love for incredibly stressful games, though it feels harder these days to justify voluntarily subjecting myself to such crushing experiences. Why give myself stress for fun when the real world is giving me plenty of it for free? Still, some unknown force pulls me into high-stress video games. Unsighted is perhaps one of the most stressful games I have ever played. A doomsday clock begins ticking shortly after the game begins, and every second that passes by is a potential death of one of Alma’s friends. Precious seconds might be scrounged up in the form of meteor dust that can prolong a person’s life in this techno-dystopia, but it’s only delaying the inevitable. The only reprieve from the constant onslaught of clock-based stress comes from an incredibly unlikely source: fishing up trash.

In Unsighted, humans have trashed the world in a neo-Industrial Revolution, clogging up the rivers and waterways with industrial junk and creating highly advanced machines called automatons. Then they accidentally made those machines sentient with a meteorite’s magical dust. Unfortunately, sentient machines are bad for unending profits and expansion. To reclaim the center of their industry, humans have placed a blockage over the meteor, stopping the dust from suffusing the air of Alma’s city and slowly suffocating the life force of each sentient machine. A little like our own collapsing world, minus the magical sentient space rock. The machines that slave away in the city’s industrial centers wish to live as dignified equals and the humans respond by crushing the rebellion of the very things that make them wealthy through genocide.

Despite its futuristic trappings, Unsighted is very much a game of the present. Calculating the cost in time of every decision I made felt a little like the cruel calculations of time and money we must compute in the present to survive runaway inflation, rent, unaffordable food, and a plague. Where the collapse of today can often feel abstract, the doomsday timer of Unsighted makes imminent doom a very real, material factor in one’s decisions. It colors every single aspect of playing the game and exploring its world. Everything is subjected to the crushing forward march of the clock; every failure a permanent death for a friend; every wasted power-up consumable a longer boss fight and lost time. The world is bleak, but the story’s focus is on hope for a better world, after all. Enter Cleo: your one hope for getting ahead of the clock and taking a breather.

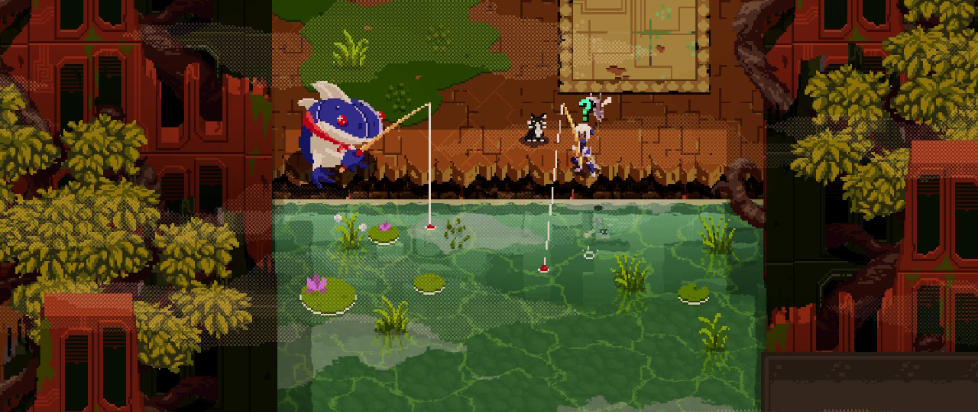

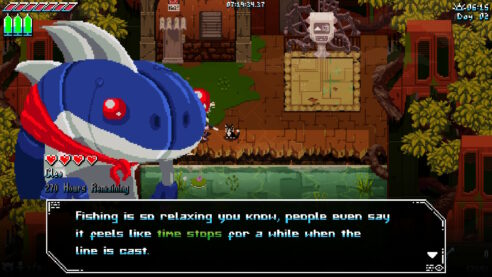

Cleo is an automaton that resembles a fish whose goal in life is to clean up the mess the humans made so that the organic fish can flourish in the ponds and rivers of the city. Cleo gives the player a fishing rod which has a magnet in place of a hook. This allows Alma to fish up junk from the water. Cleo calls this “fishing” and asks Alma to help them clean up the environment so that the organic fish can live, implying that they’re currently in danger of dying off in the city. The “junk” that Alma can fish up is a gold mine: bolts (the game’s currency), crafting materials, cogs (powerful, consumable items that give massive advantages in combat), and even meteor dust itself. Perhaps the most important part of fishing: the clock stops.

The clock has, until now, subjected the player to weighing every action against its cost and reward: how much time will exploring this area cost me? How many chests are in the area, and how much meteor dust to extend my life and my friends’ lives? Who has the lowest amount of time remaining? Can I afford exploring an uncertain lead or should I continue on the main path to finish the game? So on and so forth, ratcheting up the anxiety the slimmer the margins of error become. In order to get the materials the player needs to get ahead, the player has to pay for those opportunities with time. Fishing short circuits this loop and the creeping, imminent collapse of Alma’s world. It is the only way to gather the precious resources the player needs to beat the game without spending grains of sand from the hourglass. This seemingly innocuous activity, cleaning up the waterways for the fish to help Cleo, becomes a lifeline for a struggling player.

Alma is a big hero with big goals. Saving her friends (and wife) and liberating all of automaton-kind from human oppression shapes every aspect of gameplay and the game’s narrative beats. Living in a collapsing world, every single action taken towards that end is a zero-sum game of finding the perfect way to spend limited time before the world is beyond saving. But, when we look outside of those big, world-saving revolutionary goals, we find that it’s only possible to save the world when we look to the environment and other creatures that don’t directly concern us. Alma, presumably, has no connection to fish, unlike Cleo. Her fishing activities (and the player’s interest in them) could very well be built on selfish motives of furthering the goal of saving the world and automaton-kind. Intent on the part of Alma/the player matters little, because Cleo’s intention in teaching Alma how to fish up junk is to save the fish.

This one tiny action, the gift of a fishing rod, on the part of an unimportant background character reminds us that saving the world isn’t just about our immediate circle of friends and family. The fish suffer just as much under the very same oppression that the automatons are fighting, just in different ways. The goldmine of resources that cost nothing and the relaxing down-time of waiting for a “bite” on the line illustrate the surprising and rewarding ways that self-care and looking outside of our immediate, big-action-hero goals can have. We can’t save the world by gunning for the obvious problems; we can only save the world by taking care of ourselves, one another, and every other creature caught in the same systems of oppression.

———

Evelyn Grey is a media critic, cryptid, and Forever DM. She writes at the intersection of queer experience, class, and games. You can find them tweeting over at @Sidereal_Star, where she’s probably retweeting Pokémon fan art.