Roadwarden

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

Kids used to have this song, how did it go?

The harshest pathway leads

To the dragon’s lair

Those who search for treasure

Do you truly dare?

I met a man with no nose on the highest gate outside the largest town in the whole peninsula, a man who was the last barrier to the woods, now hemmed in between a circle of walls perpetually threatening to crumble. I couldn’t bribe him with money, which I had, but only with food; in the wilderness, money was no use to him. Trapped between a plague on one side and the forest on the other, he told me about the things that lived behind the gate: apes with fur and human faces, lizard mounts gone feral with long sharp claws. I knew that eventually, I’d have to disregard his warnings and go, bringing human maps to chart a place where the old rules simply didn’t apply.

Roadwarden is a text-based game where you play as a new initiate to the title’s trade, a hybrid caretaker (think of a witcher) who is responsible for dealing with hostile monsters, running errands and keeping the roads safe enough for travelers. You are also serving the merchant’s guild in the city of Hovlavan, assessing the Northern peninsula’s potential as a trade route, in the 40 days before autumn comes.

This constriction makes Roadwarden feel like fall. It shows the days getting colder and shorter as the seasons change, but it also distills autumn’s chill with its muted color palette and its careful descriptions of natural change. It also feels like a callback to older text-based games like Genesis, but with more integrated choice and graphics, and has the sidequest-front focus of Morrowind. To me, though, its influences are more novelistic: it feels like a cross between the Dragonlance novels and Name of the Wind, with a similar amount of food descriptions. It is low-stakes fantasy adventure, distilled.

Your most important role is as a mediator, regulating the interactions of the people living on the peninsula with the preexisting beasts and monsters who prey on them. The peninsula is hostile to human life, but humans have made a home there anyway. This image is sustained by a monumental amount of writing. Returning to the city of Howler’s Creek, to give just one example, will reward you with a string of reports on what people in the city are doing: the washerwomen laugh as their clothes dry in the sun, or a woman forgets a joke she’s telling halfway through. Without human sprites, voiceover or even dialogue, these asides conjure a living, breathing city that is proud of the walls it’s built against the wilderness, and confident that they will never fall. Not every city has this level of detail, but each has their own character, and plenty of interactions that build a sense of what they are.

Parts of Roadwarden are almost like magic. There’s a repeating prompt where you can ask people about any subject you want or search for anything (“what do you want to know about”/“what do you want to find?”) If you’ve read a fantasy novel, it’s easy to guess what the game is hiding from you, but I was amazed at how many responses the game was hiding behind these questions. The innkeeper in the first inn I found, for example, knew Quintus, the man on the gate, and considered him a friend; the guards outside thought he was a madman, though a kind one. You can also ask one of those guards about monsters (a level of intimacy I never reached) or gamble on an axe-throwing game.

All these little interactions take place in a landscape in which human efforts are perpetually overtaken by nature. There is a gate made out of living thorns, a tree that drinks your blood, and a river with birds that call to you in human screams. True, there are also orchards of fruit trees that bend to meet your hands, and a few friendly strangers who have truly found a home within nature. This is not your purview, though. You’re an inspector: every insect and fish and skeleton knows you’re not supposed to be there, and will do their best to keep you out.

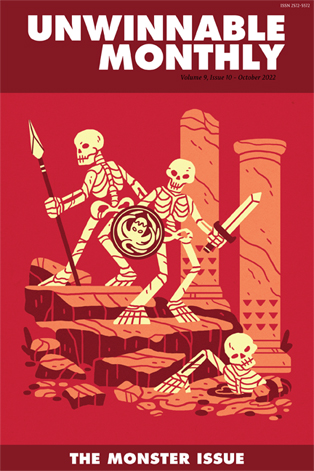

It would be simplistic, in this issue full of monsters, for me to ask who Roadwarden thinks the real monsters here are. But it’s also straightforward: the monsters are the monsters. That term doesn’t have a particular weight: the game wants you to be afraid of the deep woods, and for going there to feel like a risk even when you’re at your strongest. It wants you to feel like you’re in a fight against weather, time and your own supplies, let alone the gnashing teeth in the night.

Despite this, my time in the peninsula felt adventurous, not hostile. Roadwarden lives in the contrast between inside and outside, but it does so without creating a hierarchy. Playing it often feels comforting in the same way as a hot shower after you’ve been walking in the rain, like a full meal after a hike. It’s about traveling, but it never lets you forget that the object of your travel is to survey and assess for capital – something nature absolutely does not want you to do.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.