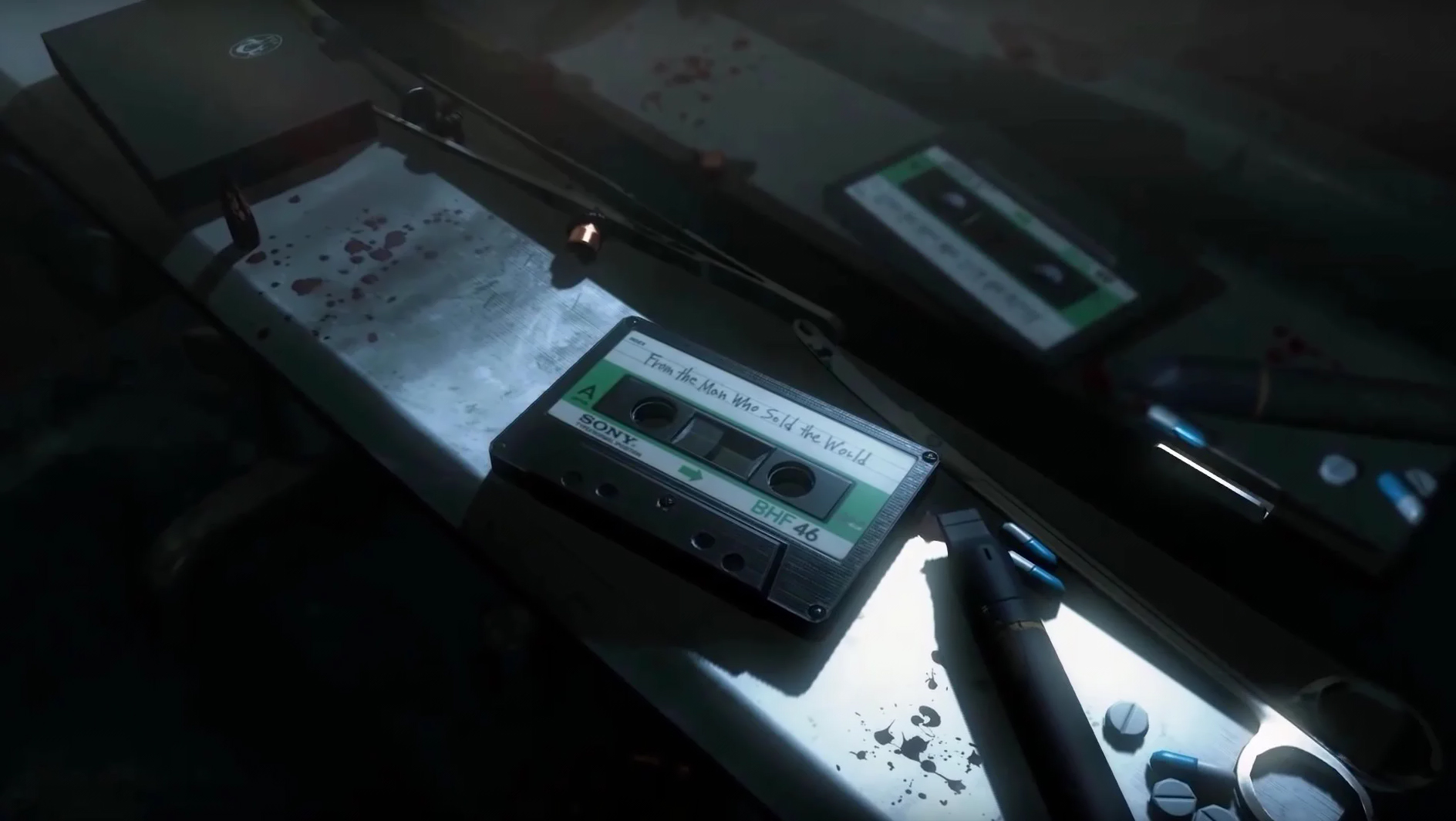

From the Man Who Sold the World

This column is a collected reprint from multiple past issues of Unwinnable Monthly. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a collected reprint from multiple past issues of Unwinnable Monthly. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I haven’t forgotten what you told me, Boss. We have no tomorrow, but there’s still hope for the future. In our struggle to survive the present, we push the future farther away. Will I see it in my lifetime? Probably not. Which means there’s no time to waste. Someday the world will no longer need us. No need for the gun, or the hand to pull the trigger. I have to drive out this demon inside me – build a better future. That’s what I – what we – will leave as our legacy.”

– Punished “Venom” Snake.

———

As the night was winding down in a pub in Brighton, a friend and I were talking about the group. He brought up something I had been trying to ignore throughout the years. How long can it last? How many of us will remain by then? The answer to these questions was bittersweet, but still underlined a hopeful message. He said that in five or ten years not many of us will be in touch. Perhaps only half of the group will even be writing by then. But I should remain proud of what I have built, getting all these people together and helping them to form friendships that will endure beyond career changes and the pass of time.

When I set my mind to create the Discord server for Into The Spine, none of this was in my plans. I never thought it would grow beyond a small group for freelancers to talk about work on a casual basis. If anyone would have told me that we would be spending the next two and a half years chatting daily, traveling across the world to meet one another, and slowly leaving our mark in the industry, I’m not sure I would have believed it.

This is the story about a private community where bonds seemed unbreakable. It’s about the ups and downs, the lessons I learned, the people that took advantage of a safe place and how I found myself relating to Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain in the toughest moments of our time. It’s also the story of how it came to an end in late 2020, and what followed afterwards.

Part One: Outer Heaven

At first, it was as haunting and unfamiliar as logging onto Twitter but seeing a couple familiar names (even if they had no idea who I was back then) gave me comfort. I endured, asking for advice every now and then and reading the channels often. The next few weeks gave me hope about my future, and I started meeting lots of new people that weren’t on my radar before. Back in late 2017, a time in my life where I was still trying to find my footing in a foreign industry and make a name for myself, I stumbled upon an industry person who was thinking of starting a group for writers. Their idea was to share freelancing tips, general advice and help to workshop ideas primarily aimed at newcomers, just like me. I threw my name in the hat, downloaded Discord for the first time, and jumped in.

This networking experience was fruitful, at least during the beginning, but I was still having a hard time trying to land pitches and pursue new bylines. There were many ideas that I just wanted to put on paper but couldn’t find the proper place for, so I had to come up with an alternative. I would follow the common practice of creating a personal blog where I could put all of this stuff while simultaneously serving as a growing portfolio in order to increase my chances.

The name I pictured was “About Gaming” for some reason, completely oblivious of the implications of the word, but the domain was taken already. I had recently finished reading Into The Wild, which had left an impression on me that I couldn’t shake, and I thought it would make for a great name. But it was still missing something. While looking for references, I searched through the songs of Supergiant Games’ work, which not only were some of my favorites but also played around with meaning in thoughtful ways. Examining Transistor’s soundtrack, I stumbled upon “The Spine.” And that was the foundation for the site.

That could have been it. A personal blog amidst dozens of others with the occasional post that probably not many would have read. I don’t remember what lit the spark – perhaps it was the forums I used to run when I was younger, or my short experience as an editor of a UK volunteer publication that was dubious at best, or perhaps all the bad experiences I had working for local sites, conflicted about an enthusiast press I didn’t want to take part of.

In retrospect, I see the spark coming from the desire to start giving back for all the help I was getting. Most importantly, I wanted to fill the gap for newcomers that don’t have access to contacts, tools and information to get started. So I decided that Into The Spine would be a site open for people across the globe, where I would take pitches and pay a $10 per contribution from my own pocket (which was a bit of a risk for a 20-year-old, considering our local economy, even if I had a somewhat decent full time job to cover my expenses). But this was still low, so as a way to compensate for it I thought that having a Discord server where I could continue supporting folks in any way possible was the least I could do.

This new server became a necessity for me, and others. That first group I was part of lost its purpose: only a handful of people would send messages into a void with no responses. Advice became a classified knowledge that only the admins held, and some of their interactions with members who were people of color left me with a sour taste in my mouth.

From there, the idea was simple. Every time someone contributed to the site they would receive an open invite to the server, with the premise of being a private freelance community where folks could brainstorm ideas, help with drafts and pitches, and just hang out. There were only a handful members for a long time, mostly folks whom I had been interacting with beforehand and pitched the site. To my surprise, pretty much all of them accepted the invite.

The group slowly started to take form. Although everyone carried their own experiences, we were all on a similar level – bylines in a couple small or volunteer sites, barely scratching a couple dozen followers. But we were eager to learn more about this job, and the industry – it was exactly the kind of people I wanted to surround myself with. Some initiatives helped to establish this: an internal spreadsheet with publications’ email addresses and rates, a document with helpful links and advice blurbs and probably too many pinned messages in each channel. The bulk of the server focused on pitching, writing, feedback, sharing our work and talks about freelancing in general. But there were also channels for off-topic chatter, multiplayer games and, eventually, event planning. Over time, as the group grew closer, we also made channels for venting and mental health.

I’ve been going back and forth on how to portray exactly what it was like to be in that server, and I think it’s impossible to describe it in full. That initial small group maintained its numbers for a while, a time in which the collective bond strengthened greatly and friendships began to emerge. While I was still figuring out the logistics of the site and playing it by ear, the server became its own thing. A safe place where people could share their experiences and knowledge with others without any sort of push back or restraint, while also receiving the same support from the other end. A place where there were both talks about all sorts of silly topics until four in the morning and talks about difficult shit that folks were dealing with. There were no arguments, no hard feelings. At one point I started seeing daily activity on the server, mainly thanks to the diversity of people in terms of locations and time zones. From that moment, it never ceased. In over two years, there wasn’t a single day in which I didn’t check on the server. And there were always dozens of messages waiting to be read.

For me, it was key to preserve this as much as possible. There was something special happening, but it could quickly go sideways. I continued inviting people after working with them on the site, but I admittedly became more selective in the process. The support and open door to give advice to folks remained, of course. But the server was slowly turning from solely a work environment onto a group of close colleagues and friends. Plus, the site had gained some notoriety, and I didn’t want for the server to become convoluted.

I started consulting with others about potential new members, and the search became somewhat different. I’d often receive a recommendation about someone who had been kind with a couple of us, or others, on social media, or perhaps a freelancer who expressed feeling aimless in their career, lacking support. But I always imposed the same rule: I would invite one person at a time, and then followed a period where they’d get acclimated with the group and vice versa. I also pushed for diversity and whenever the balance was in favor of cis-gendered white folks, I’d focus on addressing that.

By the end we were over 40 people in there. It might not sound like much considering some Discord servers, but remember that this was a close group, where inviting a new person felt like opening the doors to a house – it took us over two years to get there, gradually. I think around the 15 to 20 people mark was when there was an almost perfect balance, and many would argue that maybe that should have been the limit, but I can’t blame anyone who suggested inviting more people. I would have missed out on meeting many people I count as friends today.

At one point we thought about giving the server a community focus, splitting everything in two different groups of channels, maintaining the private aspect of the group for those who weren’t interested or preferred it that way, and opening the door to all of those I was meeting through Spine or on social media. This never led anywhere, but honestly, the thought of making a super group contradicted what I wanted from it in the first place. Making it fully public was never in question for me and I’m glad that was the case – I’ll go back to this later.

We became a group so united, so acclimated with one another. This was showing, both in our notoriety as individuals and as a collective force. If someone had questions about how to deal with a certain situation regarding work, there was always a person eager to help, regardless of time and day. Our internal knowledge was crafted from pure experience. There was a level of transparency that still amazes me to this day, especially since, well, we were all competing with each other. But we always punched up, not down. Whenever there was a job opening you’d see someone showcasing interest and another person replying, “Ah, that’s fine, you should go for it.” But the response was always, “We’re both applying to this.” If a site was late on payments, or an editor was being rude to one or more of us, we would take notice. In the most severe cases, that publication would suddenly stop receiving pitches from around 30 writers.

I recall very vividly how the people in charge of the first freelance group I took part in always mentioned hearing things from “whisper networks,” a term employed as an excuse whenever someone asked for details on something, bragging about an unreachable access for us, the people at the bottom. Ironically, we ended up becoming one ourselves . . .

Part Two: Deeper Than Hell

The question was, where could we take it from there? It seemed like there were no limits to what we could accomplish. We toyed around with the idea of a pitch jam, providing feedback to folks based on what we knew. There were some early plans for starting a freelance union. “Plans” might be an overstatement – we quickly realized it was not an easy thing to achieve. On my end, I’d often joke that if I suddenly got rich, or a parent company would acquire the site, I already had the perfect staff for it.

Once the 20-person group started growing further, some new dynamics, ones that weren’t visible until much later on, rooted into place. Having such a strong bond meant being there for one another on every occasion and especially when someone needed the support. For a long time, this was all addressed internally in the venting channel. But in some situations that involved people from the outside, mainly on Twitter, this collective energy started to reach outside the server. I believe that some people had it coming. Others, not so much. Especially not from, when viewed from the outside, what seemed like a mob. That’s when I realized exactly how big a group we were.

The personal expectations of some folks got a bit too tied up with the rest. That meant that if someone was on a byline streak, people would feel like they weren’t doing enough. Situations, backgrounds and experiences were unique to each. I thought that would put enough distance for everyone’s personal expectations but I didn’t take notice of the imbalance for some until they started bringing it up. There was no easy solution for this.

Even if some people were still juggling jobs and studies while doing freelance, even if they were in a completely different position compared to those who were knee deep in full time writing, even if we had all witnessed the effort that every single person in there went through to get where they were, insecurities and peer pressure crept in and never left.

I learned that when professionalism and friendship intertwine as much as they did for us, cases like these are inevitable, and at times without a possible fix.

It’s important to keep this in mind, because it didn’t become fully visible until close to and during 2020, at least for me. During our peak I’d often felt a sense of pride and excitement that came from seeing my peers and friends achieving their goals and surpassing milestone after milestone. But it was also present whenever I witnessed folks banding together to defend one of us, and it was hard to keep my head in the ground, and not get too comfy. Less than a year later, a group that never needed moderation was screaming for it. What we thought to be a safe place to talk about anything was disrupted and could never be brought back to what it once was.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain tells a story of revenge, regret and remorse. Punished “Venom” Snake, along with Kazuhira Miller, witness the destruction and death of their base of operations. Under the name Mother Base, the facility was born from the vision of building a separated nation, an “outer heaven” for soldiers the world over to live and work outside of governments’ exploitation. It was a mercenary army ready to take on any job that came through their way. After the attack that destroyed the first Mother Base, it became an army led by anger, driven by the pursuit to rebuild their home, and themselves, preparing to get back at the people who infiltrated their walls and tore their sanctuary apart from the inside.

Punished Snake and Kaz barely make it out alive from said attack, the two of them suffering the loss of limbs, and Snake ending up in a 9-year coma. After recovering, they both set themselves on a path of retaliation, alongside an army that grew bigger and stronger by the day. They both suffer from a shared phantom pain – one not only physical, but emotional. “Cipher sent us to hell, but we’re going even deeper,” Kaz articulates. Snake remarks that they’re not fighting for the past, but for the future. But it’s clear that they won’t be able to move on until they settle the score, regardless of the cost.

All of the problems that had started to take place in the server were aggravated as we invited new people. Conversations were harder to follow and this, understandably, pushed some folks away.

In early 2020, I flew to the UK, where I reunited and met even more friends that I had been talking to pretty much every day for years now. I came back from it unaware of the pandemic that was about to hit the world and our lives, making plans to meet up again at other events throughout the year, determined to continue focusing on work and save up enough money for the trips. And I was completely clueless about the fact that I’d find myself disbanding the group before any of this could happen.

Once quarantine became an actual thing, the activity in Discord was higher than ever, but it was a different level. Not only were we all prohibited from continuing with our normal lives, but our work was heavily affected – publications fired employees, sites and divisions were shutting down and freelance budgets went on a freeze (fun fact, the EGM fundraiser was first brought up in our group, but I agreed for that idea to take actual form elsewhere).

Only a couple weeks before all of this, I had left my office job to pursue writing full time. Others were on the same boat. While the rest had been working towards this goal for a while now. Many of us were already lacking the security that comes from salaries. Our possibilities shrank exponentially – saying that our morale was low doesn’t even begin to describe how we all felt.

Uncertain about the future but trying our best to stick together and hope for good news in our particular situations, the group began to drift apart. The state of the world didn’t help to navigate our usual workplaces. Twitter became even more toxic than before, with everyone being worried about their financial stability, angry with governments who once again proved they didn’t care for our safety and security and on edge about the sniping and discourse.

All of this started to permeate the server. Channels for venting and mental health weren’t enough. And when the same attitudes that we often despised from the outside became the norm for us as well, it all became harder.

To make things worse, many of the other problems that I was unaware reached a critical point. I’m not framing this in a way to redeem myself. From my perspective, this was a healthy and safe community without arguments and hard feelings – one that could sustain itself without moderation and without my constant presence during busy weeks.

But if I would have kept at least one eye a bit more open, maybe I would have been able to catch some of these problems early, preventing them from snowballing in the background. I would usually reach out to folks who had been inactive, asking if there was anything me or the group could do.

One person reached out to me mentioning how they and a couple more folks had started to feel left out, among other things, and asked if it would be possible to bring this up to everyone in the group. So, I said yes, set a date and we all talked for hours. I’m glad we did this as more people were able to articulate some of the feelings that had been on their minds. But it also meant seeing one of my closest friends, whom I had invited to the server years before this and cared for it as much as I did, standing their ground against every comment.

A tough climate followed during the next few weeks, for all of us, both inside and outside the server. As protests around the world ran rampant, as TV and social media brought nothing but bad news and as our jobs continued to be uncertain, there was a situation that broke us apart in irreparable ways.

A person who had been with us pretty much from the beginning and had remained part of the core group as an advisor, a colleague and a friend for most of us, turned out to be an abuser. One that had been operating within the industry in the background for years, manipulating and hurting people, some of which were members of the server.

I wasn’t quite certain what was happening until I began seeing screenshots and statements. In the server, we had a private channel for what was considered the core group – at first it had been born from the idea of people helping with the site, separated from the rest as, again, they were different things, but we never got to use it for that purpose. Instead, it served as a place to discuss the amount of channels, propose people to invite and to have emergency talks. I revoked this person’s server permissions and some of us concentrated in the private room as we watched it unfold live.

I choose to be transparent about this because it’s important to showcase how the process was for us, and especially for me. There were different reactions – at first, I was waiting for a public or even private statement from this person, but I was being too hopeful. Others were also uncertain, while some couldn’t believe how we were doubting and turning our backs on someone as close as her. But this was all around the first few hours.

Each one of us came to terms with it and the response ended up being unanimous. Yet, this also brought to light problems that had been present for long – how quickly we would judge, and act, upon certain situations without double checking, without thinking things through before taking things outside the server and into the public eye. That day several folks left, both because of it and as a way to get away from it. Some of them never asked for a new invite.

The aftermath was tough. We weren’t just finding new bits of information – we were discovering someone we thought we all knew in a brand-new light. And this, too, applied to more people – our internal blacklist had several industry names this person had brought up throughout the years as people to stay away from, leading an entire community to turn their back and whisper to others, about innocent folks. This is a person I had met in person during two trips, whom I had laughed and shared moments with. I reached out to them and received nothing but cold answers stripped of any semblance of regret in reply. Recovering from it took a long time. For months, all I talked about in therapy was this and the problems of the server.

This wasn’t the first person who took advantage of the server. We had similar situations. One writer left on their own, letting me know privately that he didn’t want for the server or the site to be affected by his presence. Another left after a long, racist rant that the server witnessed in plain sight. I ousted two others, one of which sent message after message from asking for a second chance. The group lent me their support for these unexpected and difficult incidents.

For months I’dd wake up and immediately check my phone for new messages or mentions, catching up with anything I might have missed while I was asleep and dealing with problem after problem. The server became unsustainable, toxic and harmful for many. I seemed trapped in a place where my mistakes were shown to me, time and time again, and it was too late to do anything. A couple folks started helping with moderation, for which I’m grateful for, but this was all present in my head 24/7. I felt guilty about everything. I was seeing peers leaving a place that used to be so special to all of us. I witnessed one of my closest friends’ anger towards me grow each day, our bond breaking apart in ways that will probably never be restored. And I had an incommensurable rage towards those who had torn my trust into pieces. I’ll never forget their names, and the damage they caused.

Finale: The Man Who Sold the World

We were the so-called clique, the Phantom Thieves, the Diamond Dogs, that one freelance server everyone wanted to be a part of. And it all crumbled before my eyes in ways I never could have imagined. It was a group so pure, filled with some of the most kind and talented people you see and read every day, one that held a bond that seemed like it would survive even the worst storms. I kept it opened for a couple more weeks as I debated myself as to what to do with it. This period of my life got me out drinking my problems away, filling my days with as much work as possible to keep my head occupied, dealing with a pandemic and the uncertainty of the future and trying to cope with the fact that a person who had been very dear to me had ended things less than a year before, but didn’t exactly set the distance we needed until I asked for it.

After months circling around my options and the future of the server, I decided to disband it on August 31st. During the weekend before I reached out to everyone who was still there privately to let them know, thanking them for making the space what it was and apologizing for how everything had turned out in the end. In the final hours, many people shared long, heartfelt messages saying how much this space had meant to them. I told them that regardless of where they end up in life, they will make that place a little bit brighter with their presence.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain doesn’t have a proper ending. The third act of the game lives only in a leaked, incomplete video, alongside notes and concepts of what it could have been. The server didn’t have the end I pictured for it, either. But there’s no hidden tape, no B-side to this story. From the Into The Spine server, four separate private groups were born during the last few months and those are only the ones I’m aware of. The only remnant of better times can be found in the site’s freelancing guide, a testament of our commitment to not hide our knowledge behind a paywall or privileged access. And that’s something I’ll remain committed to as I continue working on the site. I’ve commissioned and given feedback to hundreds of people at this point, and I hope to be able to keep on helping many more in the coming years.

It’s odd to think about how I’ve met enough new writers in the past year that I could basically do another server of the same size, if not bigger. And it has crossed my mind a number of times. But despite having healed, recollecting my memories for this piece, I don’t think I have it in me yet. I don’t wish anyone else in their early 20s a fraction of it. But the necessity remains, as much as the gatekeeping in the industry. I believe there should be more spaces like ours, but I don’t think they should be public – some of the worst people in this industry will always find ways to return, or to mask their true intentions and can turn communities upside down. Leaving an open door to them in public servers where former or future victims are exposed is irresponsible.

What we do need is more solidarity, more transparency and willingness to help others. Sharing an email won’t immediately end your career with the attached publication and responding to a DM can literally change people’s lives. The power imbalance between editors and freelancers is huge, a fact that is both overwhelming and unknown to newcomers. But spaces like this can help to spread the word around, even if it’s done privately to a dozen people, and with curation in between – it makes a difference.

Right now, everyone is scattered doing their own thing, and I’m glad to see that most of us have been able to move on onto better things. 2020 was a transformative year for me in many ways, and I wish for nothing but the best to the kind and supportive people that were present during the toughest times as much as the happiest. Who knows what will happen in the next five or ten years. Perhaps not many of us will be in touch. Perhaps only half of the group will even be writing by then. But I’ll treasure them forever.

I went deeper than hell to chase my demons, but I don’t know what my phantoms will be. It was always hard to grasp the influence we had in the industry. I’m still unaware of it and will probably remain as is for years. I might have sold the world, but I really hope people can learn from my mistakes, and rebuild what I couldn’t, using it as a foundation to help the coming generations. I’ll continue working on my end to make that happen.

Until then, one thing is certain. This pain is ours, and no one else’s.

———

Diego Nicolás Argüello is a writer from Argentina who has learned English thanks to videogames. He also runs Into The Spine and is objectively bad at taking breaks. You can catch him procrastinating on Twitter @diegoarguello66.