Looking Back While Moving On

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #131. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #131. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

A videogame deep soak.

———

Nothing about Family is real, except for the nostalgia.

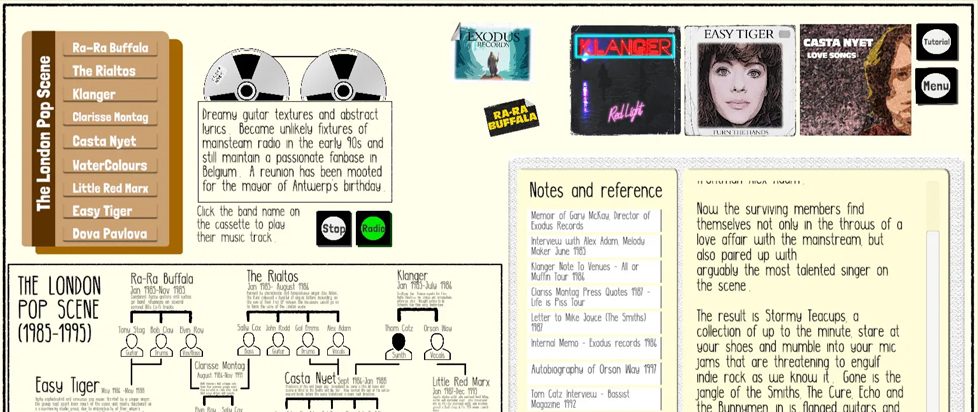

The songs aren’t real. They were written for the game. The found family that populates its cast never existed, and 91.5 Sussex FM, the radio station that provides the soundtrack for the game’s hour or so of gameplay, is completely made up. You probably wouldn’t realize that, though, if you’d played Family without reading this or the comments on its itch.io page.

Family is a game of logic puzzles. It invites players to complete a musical family tree using clues gathered from a radio interview with one of the bands’ members, by flicking through the music of the bands themselves and from foraging for information among extracts from memoirs, a band’s rider and record label memos. You don’t need a microscope to see the DNA of Return of the Obra Dinn.

The game is inspired by the London indie rock scene of the late 1980s – inspired by the music but probably more so by experiences and bands that once were – but the key to its success isn’t the long lost past. I don’t care about this kind of music, these non-people and their never-stories. The key is where Family situates its player: in modernity, as listeners to a local radio retrospective and readers of the scraps of text that supposedly remain.

The game is inspired by the London indie rock scene of the late 1980s – inspired by the music but probably more so by experiences and bands that once were – but the key to its success isn’t the long lost past. I don’t care about this kind of music, these non-people and their never-stories. The key is where Family situates its player: in modernity, as listeners to a local radio retrospective and readers of the scraps of text that supposedly remain.

The backward-looking British local radio feel. The Space Raiders and Egg and Cress sandwich on the rider. The types of egos that you might have met through a mutual at uni (if you were unlucky). The specificity of the player’s situation makes Family’s abundant nostalgia a phenomenon that can be parsed and understood by anyone, including those who don’t treasure the music the same way the game’s creator Tim Sheinman obviously does. It promotes empathy and allows the emotional framework behind Family to be transported onto other reference points for nostalgia. In my case, Smashing Pumpkins, Buffy, Duckula, Robocop.

At first, I felt like the detective mechanics – the main hold-over from Obra Dinn – were an awkward fit for the theme, the same kind of clash of story and action that makes me wince any time I stumble on a hidden object game. The more time passes since I finished Family, the more I think it’s the game’s master stroke and the main reason it succeeds in creating an authentic-feeling past where other games with similar aims might not. Family is a game about piecing together identities and stories from fragments of sound and text. As evocative and crisscrossing as those fragments might be, they remain just debris, offering only a partial view of reality, even when the piecing together is done. The less complete the picture is, the more authentic it feels: the fragments become more than the sum of their parts in a way that that cliche rarely merits.

Looking backwards also lends Family’s nostalgia the benefit of a dose of reflection. Sure it has the bittersweet quality that infuses a lot of exercises like it – gesturing at the inevitability of time’s passing, of loss, of the impossibility of recapturing something gone (that ultimately never existed in the first place). But the game escapes from the sentimentality that often accompanies such bittersweetness by alluding to the darkness as well as the light beneath the music, to addiction, personal and interpersonal chaos. Perhaps the saddest stories are those that are left open, the names who figure big in Family’s earliest mysteries but, intentionally or simply due to the fact of their puzzle having been completed, fade away, leaving players to wonder if those rockers got lost in addiction, are still covering Oasis songs in a Camden pub every other Friday night or gave it all up to work in IT.

Looking backwards also lends Family’s nostalgia the benefit of a dose of reflection. Sure it has the bittersweet quality that infuses a lot of exercises like it – gesturing at the inevitability of time’s passing, of loss, of the impossibility of recapturing something gone (that ultimately never existed in the first place). But the game escapes from the sentimentality that often accompanies such bittersweetness by alluding to the darkness as well as the light beneath the music, to addiction, personal and interpersonal chaos. Perhaps the saddest stories are those that are left open, the names who figure big in Family’s earliest mysteries but, intentionally or simply due to the fact of their puzzle having been completed, fade away, leaving players to wonder if those rockers got lost in addiction, are still covering Oasis songs in a Camden pub every other Friday night or gave it all up to work in IT.

Family lives for nostalgia, but it’s not saying that things used to be better in the good old days. It’s just saying that it misses those old days, both the good and the frequently bad. The game’s in a comfortable place, still loving that old life, recognizing all its flaws. That’s something that I think it has in common with the best modern nostalgia pieces, even those with very different tones, aims and narratives. Stranger Things, She-Ra and the Princesses of Power, Super Meat Boy, Gone Home, Broforce (of course). They demonstrate a way to do nostalgia that strikes the right balance: faithful without closing their eyes, looking back while still moving on, building worlds on top of and out of the past rather than simply re-creating what was there.

———

Declan Taggart is a doctor of viking gods. He lives in a faraway land, but you can probably find him on Twitter @DCTaggart.