Evangelion and Endings

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #117. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #117. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface

———

When I was in high school, I assumed I’d be into anime forever. I was the president of our small anime club, I drew anime characters in the margins of notebooks and built GeoCities web pages devoted to my favorite characters. I even planned on and ultimately wound up taking Japanese in college to better understand the shows I was so fond of. Then, in the midst of senior year, I started watching Gainax’s Neon Genesis Evangelion (via VHS bootlegs picked up during weekly trips to Elizabeth Street Mall in Chinatown). Two decades on, while I still follow Studio Ghibli’s latest and might catch an episode or two of whatever franchise is burning up everyone’s tongues, Neon Genesis Evangelion remains the last anime series that I seriously watched.

It’s no coincidence, either, that Evangelion was the series that indirectly capped off an entire trunk of my media consumption habits. It’s a painful and often confused mess of a story that, regardless, succeeds at tearing down many of the assumptions and clichés long embraced by the massive industry that precedes it; making them all much tougher to swallow later on. It may borrow aplenty from the nerdy empowerment fantasies that anime famously trades in, with teen Mecha pilots saving the world from waves of monstrous “Angels.” But this superficial layer is worn away with every minute spent watching the distorted and fractured vision that makes up Evangelion’s twenty-six original episodes.

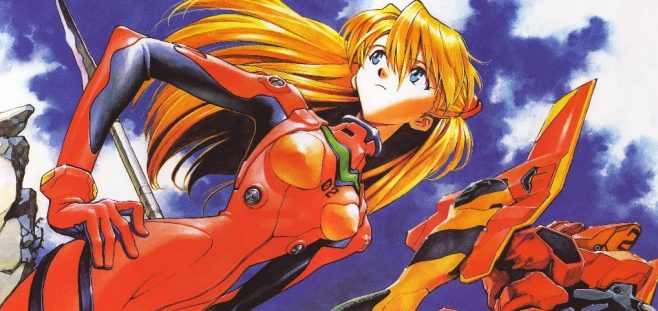

It’s difficult not to be immediately bowled over by the many contradictions of the series. Because, in spite of the thoughtful material that it often descends into, Evangelion remains an anime-ass anime. As complex as the show’s characters ultimately wind up being, they still lean heavily on a bevy of cheap and clichéd traits. Its women are either hyperbolically sexy pin-ups or childlike, innocent Lolita dolls. The men are either emotionally muted walls of propriety and honor or infantilized, supplicant figures, harmlessly perverted, their drooling faces eagerly presented for aggrandized slaps. During intimate scenes at home the camera hovers perpetually in between Misato’s thighs or leers down Asuka’s crop tops. And in spite of the background of psychological torture that supports the show’s action moments, the robot fight scenes remain bombastic spectacles, largely peerless within the Mecha sub-genre. The power fantasy is still there, if you’re OK not turning it over and examining what’s wriggling underneath.

Watching as a teenager, many aspects of the show felt wrong, wrong enough to sour me on an entire media subculture, even. It wasn’t that I had any trouble parsing and enjoying the surface fantasy, catered as it was to my gaze and circumstances, but I couldn’t entirely swallow something so evidently twisted, so achingly hollow. It took coming back and watching the series again in my mid-thirties to truly wrap my head around everything Evangelion was doing, both as a commentary on genre and a psychological study of a group of painstakingly crafted, emotionally broken characters.

Two decades afford plenty of room for contemplation and shifts in perspective. High school Yussef had posters of Rei Ayanami on his wall, and fantasized about her quiet mysteriousness, her surprisingly mature outlook. Observing her arc as an adult, I see a frankensteined mommy figure, not a person so much as a walking traumatic memory kept aloft by her attachment to the living members of the Ikari clan. She certainly does have a bizarrely mature outlook for an adolescent girl, but this only serves to make her story all the more sad and horrifying. Evangelion twists the Lolita character cliché with Ayanami, putting an ancient and unknowable figure into the body of a child, joining the oedipal currents of maternal love and sexual fixation into one barely held together body, trying to absorb it all.

Asuka Langley Soryu is another character who has so dramatically shifted under my aging impression as to be nearly unrecognizable. Unlike Ayanami, Soryu is brazenly, messily, human, and the distinction defines her character in stark, painful relief. Her personality is shaped by her depressed and suicidal mother, who took her own life and left Soryu orphaned. This trauma leaves her insecure and cripplingly narcissistic, someone who craves the attention of those around her even as she pushes them away. Her behavior confounded my own teenage perspective as profoundly as it does Shinji Ikari’s in the show. She’s a character you can’t help but care about, but who won’t let herself be easily admired, or loved.

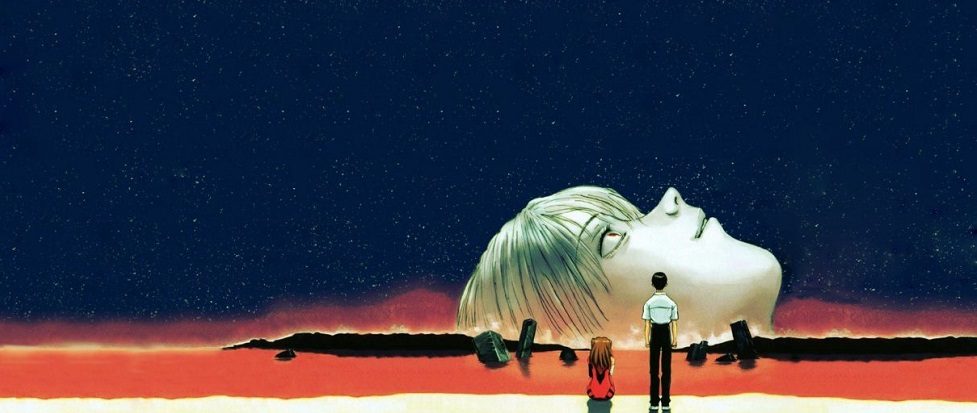

When I first watched the series, Soryu was an emotional dead end. She remains that way if you don’t watch the movie released a year later, End of Evangelion. In that movie, even though she does not succeed, Soryu stops running from the trauma that formed her, recognizing instead the humanity inherent in the pain and separation she lived through. Riding the wave of self-satisfaction born of embracing an inherent truth about herself, she becomes as powerful as she has ever been, takes on insurmountable odds and veers as close to triumphant as the series’ creator Hideaki Anno, ever allows.

Auteur theory tends to be overused as a tool for talking about films and their directors, but Evangelion is unmistakably Hideako Anno and Anno is unmistakably Evangelion. This has only become more clear to me after years of working in the arts and struggling with the results of my endeavors. Making yourself vulnerable and opening up to the rest of the world is a brave act partially because there is absolutely no guarantee that it will pay off. Sometimes you get in the damn robot and fall on your face: your peers ignore your output, you shout into the void and receive nothing in return. Sometimes someone whose opinion you hold highly compliments your work and buoys you for weeks and months to come. Apart from being a show about trauma, Evangelion, is also a show about trying to create something, trying to make your mark on the world and become confident in your own abilities.

Anno’s proxy in this respect is Shinji Ikari, the centerpoint around which the rest of the show revolves. Watching Shinji back in high school, I also saw myself in him: a shy boy who didn’t quite know how to fit in, who was never able to stand up for himself. I saw my own petty crushes and confused adolescent self-torment. Now I see him for what he clearly is: the epicenter for Anno’s exploration of his own psyche and his own struggles with depression and shame.

Shame, real visceral shame, sits firmly in Evangelion’s wheelhouse as it rarely does in other anime. Sexual antics abound in the medium: an accidental upskirt, finding yourself in the wrong changing room, tripping and falling on a character of the opposite sex and touching an inappropriate area. When it happens: a slap, a yell, a casual accusation of “pervert” before things are smoothed over with near immediacy. But in Evangelion, which is replete with similar stuff, it doesn’t really go away. Instead, Shinji’s shame builds up, poisoning his relationships, seeping into the cracks of their foundations like some invading angel.

Through this fogged-over prism of his shame I see Anno’s troubling relationship with women, I see maternal longing and compartmentalized sexual desire. It took getting older and looking back at myself looking at this show to understand why this resonated so well with my frustrated, but ultimately blinkered teenage outlook. It took comparing how Evangelion struggles with the disappointing traits of Otaku culture with other shows, that don’t even bother to make the attempt, or that lampshade their pitfalls without any further self-critique. What’s the point of watching something that won’t let me look past the gleaming robot plate armor and show us a glimpse at the ugly gristle and sinew?

I admit that there are likely shows and films outside of my remit that have done service to Evangelion’s legacy. But, as in the case of videogames (with which my relationship grows more tenuous with each passing year) the bad tends to overshadow the good, both in ubiquity and relative volume. Evangelion started something by struggling with itself, with its history, with its shortcomings, that I’m not convinced was successfully carried on by its contemporaries into today. It created a world full of pain and mistakes and trauma and sexual perversion and tried to destroy it, again and again, through successive re-edits and sequels. But it lives on, like some twisted Angel, blithely un-self-aware, endlessly replicating, seemingly eternal.

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and visual artist from the Bronx, NY. His specialty is graphic design for television but he also enjoys thinking and writing about games.