Procreation of the Wicked

In Clive Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart, the jaded libertine Frank summons a corps of demons known as Cenobites because he wants to fuck on an otherworldly level, fuck without all the adjacent concerns that burden us here on Earth. “He had thought they would come with women … oiled women, milked women, women shaved and muscled for the act of love.” Frank’s unparalleled hubris, that he would summon beings who “a handful of humans” had ever laid eyes on and have them do his sexual bidding, is rewarded with sensory obliteration.

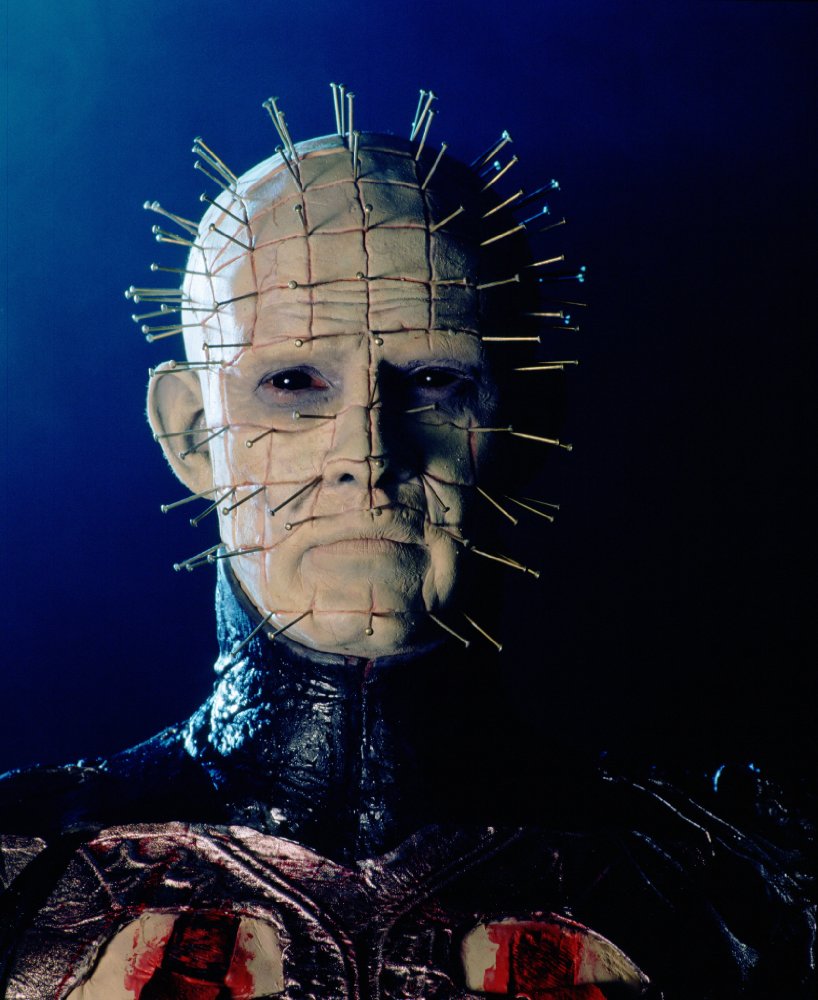

But the thing about the Cenobites is that what they do is pleasure. Frank dreams of simple rutting, but the Cenobites are unearthly sadomasochists. Their obsessively ordered flesh, flayed and stretched and impaled, is how they get off – an exalted, ritualistic perversion. Their bodies are shrines to their faith, physical manifestations of a monastic devotion to “the further regions of experience.” Frank refers to them as hierophants, or interpreters of mysteries; they untangle the puzzle of flesh for their summoners.

The Cenobites are first described through Frank’s eyes in specifically othering ways. They’ve mutilated and scarified their sex organs; Frank is unable to guess their genders “with any certainty.” Pinhead, who like the others goes unnamed in the story (“Pinhead” in the movies, while Barker’s later, ill-advised The Scarlet Gospels refers to it as the Hell Priest), has a light, breathy voice – that “of an excited girl.” It wears a dress.

Frank, to the dismay of his libido, is initially repulsed by the Cenobites. “These sexless things,” he calls them. If he can’t fuck them, what good are they? Their bodies are inaccessible, skin sewn into clothing and the other way around, pierced by chain and punctured by pins. He balks at their “queer deformity” and “self-evident frailty.”

Frank, to the dismay of his libido, is initially repulsed by the Cenobites. “These sexless things,” he calls them. If he can’t fuck them, what good are they? Their bodies are inaccessible, skin sewn into clothing and the other way around, pierced by chain and punctured by pins. He balks at their “queer deformity” and “self-evident frailty.”

“Queer” is a revealing choice of word. The Cenobites, with their sadomasochistic overtones and scarified bodies, and their relationship with Frank have often been read as queer – though the tenor and intent of those readings has varied wildly. At Offscreen, Colin Arason offers a thorough reading of the Barker-directed 1987 film adaptation, Hellraiser, as the story of Frank’s metaphorical sexual awakening – an admirably thorough analysis, which cuts cleverly through the film’s corny slasher-style climax. Frank, not the Cenobites, is the film’s monster. Hellraiser finds him ashamed of his desires; when he summons the Cenobites he specifically imagines them arriving flanked by women, but in the end he welcomes destruction at the hands of the genderless, sexless demons. They rip him apart as he grins, nerve-endings aflame with the liquor of pain, finally accepting an eternity of obliterative bliss.

Agony, a game in a vaguely Barkerian sex-death vein by MadMind Studios, is mostly about how horrible it is that vaginas bleed. All its art direction is, aside from ugly, yonic to an obsessive degree. The villainess has one vagina between her legs and another yawning on her back. Being developed by men, it equates vaginas to women, one the same as the other and both of them treacherous and diabolical. Shockingly, there is no space for gender play here. Infernal cock fucks infernal cunt for eternity – they’re one step from missionary-only orthodoxy down in Hell. Worth noting that Agony’s promo materials boast of such terrifying chthonic sights as “brutal sex scenes” as well as “lesbian and gay sex scenes” (non-brutal?), lending further credence to the trembling conservatism of its worldview.

Agony is glistening and red, painted in blood and lit by fire; the stereotypical western vision of hell, because it offers nothing new. It is a broken, idiot game with nothing but rote gore and sexual violence up its sleeve, wholly unworthy of attention – attention being the exact thing it’s dying for.

The film critic Robin Wood talks in Freudian terms about horror being the return of the repressed; a bubbling-up of sublimated urges and desires held by both the characters and the audience. Frank’s perverse coming out surfaces passions not even he knew he had. The Cenobites come when they are called, answering a desire beyond admitting and, in a way, do what they are asked to do. There is real, primal allure to the thing in the night that aches to curve its fangs gently into your throat; decades of horror fiction explore this idea. BDSM is, like, a thing; it’s hard to imagine a little rough play shocking anyone who’s likely to come across Agony, but it, and other would-be extreme games of its ilk like Lust for Darkness or Outlast 2, are at their core afraid of sex. They aren’t about repression; they are themselves repressed, timid things that have no idea how quaint they really are.

———

Astrid Budgor is a writer and editor living in Florida.