On The Black Belly of the Tarantula

Giallo film was a cycle of Italian murder-mysteries that flourished for a few decades in the mid-20th century. Giallology is a humble appreciation of these movies.

Released in August 1971, not two weeks before Luigi Bazzoni’s The Fifth Cord, Paolo Cavara’s The Black Belly of the Tarantula gives us a clearer sense of the brutality and fetishism that came to dominate the giallo. It is, in fact, the film’s only real merit.

The Black Belly of the Tarantula was Cavara’s only giallo1. It stars Italian cinema heavyweight Giancarlo Giannini, who worked with Lina Wertmüller, Ranier Werner Fassbinder, Lucino Visconti, and Sergio Corbucci, and a handful of giallo mainstays and/or Bond girls like Rossella Falk (The Fifth Cord), Claudine Auger (Thunderball), and Barbara Bouchet, who worked with Mario Bava and Lucio Fulci. Ennio Morricone provides yet another giallo score, and Marcello Gatti (The Battle of Algiers) shoots.

This cross pollination tells us that while giallo today is a curio, one of many lost avenues into which the intrepid viewer can wander, giallo at the time was popular cinema. In his La Dolce Morte, one of the few book-length studies of giallo, Mikel Koven calls it “vernacular cinema”—intended not for the arthouse or international audience but for rural & suburban third-run theaters, where audiences had different expectations and critics rarely tread. The audience would chat during the movie, react raucously to kill scenes, and generally treat the theater as a social space.

“Vernacular cinema therefore tends to be an obvious cinema—what is important needs to highlighted, often repeatedly, not just through repetition in the script, but also visually through repeated flashbacks,” Koven says. Thus the oddities built into the giallo formula; the one-and-done red herrings, the repeated insistence that the protagonist knows something important, and the inevitable recap of the film’s events at the dénouement for anyone who missed anything.

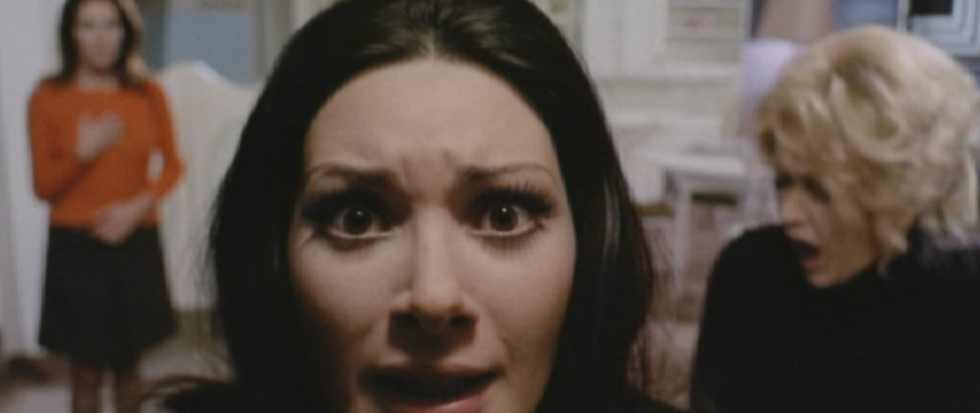

The Black Belly of the Tarantula adheres closely to the template set by Bava and Dario Argento; its first murder scene is a self-conscious one-upping of the bedroom murder in The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, where the killer cuts through a woman’s nightgown with scissors before thrusting them between her legs. Argento leaves the physical violence of the scene implied with a cutaway to blood splattering on a pillow at the moment of impact. He emphasizes the suspense of the scene instead, elongating the space until the inevitable happens.

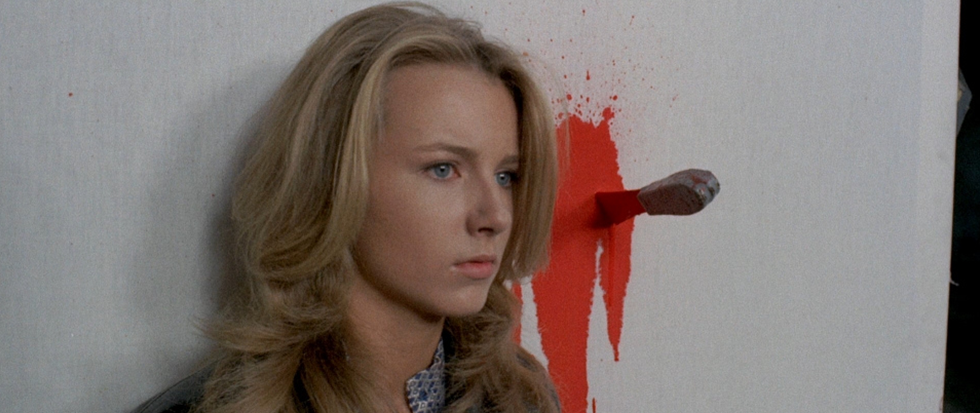

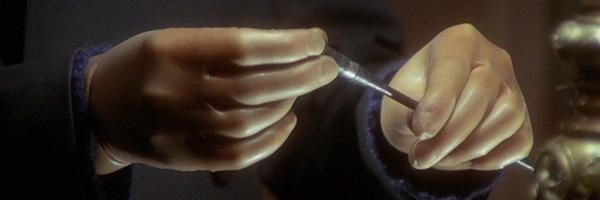

Cavara shows us his victim being killed in full detail, using the giallo fixture of a precise, fussy method of murder. Here, the killer splays his victim on a bed, strips her, and injects her with tarantula venom, which paralyzes her but keeps her conscious while he eviscerates her. To no one’s surprise, we learn later that this gives the killer “pleasure.” Cavara throws in a close-up of the knife running across the woman’s belly for good measure, although this is the most graphic shot in the film and the violence is stylized, to an extent—no gore, just blood.

From there, the most distinctive thing about The Black Belly of the Tarantula is its protagonist: even before the whole murder spree starts, Giannini’s Inspector Tellini isn’t sure he wants to be a cop any more. Giannini plays that reluctance well, although Tarantula’s dub is remarkably bad—everyone speaks in double time and certain lines sound dubbed by two separate people. Morricone’s score has one dynamite main theme and a whole lot of meandering, piano-plunking “atmosphere” that Cavara slathers over nearly every scene.

The film’s style is middle-of-the-road; never incompetent, but never rising above the formula either. Gatti’s cinematography gives the requisite mod fuck pads and bizarre glass-paneled houses their due with plenty of long shots, and he has a very 70’s fondness for abrupt snap zooms.

There are some toothsome, weird touches at the fringes, like a PI who wants to be called “the Catapult,” a scene where the actors are suddenly talking into camera Jonathan Demme-style, and a genuinely dangerous rooftop chase where it feels like everyone is one false move from careening off the edge of a twenty-story building. When someone does, it’s a comically obvious dummy who bashes limply into a window like a tossed rag doll. The film climaxes with an extended hand-to-hand brawl that destroys Inspector Tellini’s apartment, a throwdown that could come from an 00’s Korean thriller.

The killer is motivated by impotence, carrying on the proud giallo tradition of depicting straight men as pathetic hair-trigger losers who have built cathedrals of pathology atop their sexuality. Tellini not being cut out for the police force—quitting, at the end of the film—also suggests a critique of brutal masculinity. He cuts off the psychologist giving him the rundown of the killer’s profile, saying “Please, no more. I’m not up to it.”

However, Cavara is not so studious as Argento was to avoid sexualizing his victims—moreso than the other films we’ve talked about so far, The Black Belly of the Tarantula lingers on naked women, even making its murderer a masseuse to treat us to plenty of close-ups of thighs and asses. This titillation combined with the ritualistic killing method—hinted at in predecessors like Bava’s 1965 Blood and Black Lace—makes Cavara’s film a good template for the “typical” giallo. This is the kind of thoroughly competent work that characterizes the genre; murder mysteries with a bit of flair and enough money shots to keep the audience happy.

1Cavara’s 1962 debut Mondo Cane (A Dog’s World) spawned its own genre of exploitation film, the mondo film, a type of mockumentary which depicts “foreign” cultures as savage and grotesque and perhaps peaked with 1971’s insane Goodbye Uncle Tom. Mondo films mutated into stuff like Faces of Death and cannibal movies, which mostly dispense with any ostensible educational angle and go straight for the gore. The twinned ethnocentrism and xenophobia of the mondo genre could be read as implicit in The Black Belly of the Tarantula, given that the murderer uses acupuncture needles to paralyze his victims.