“Licking Wounds” – Bungo Stray Dogs Vol. 3

Atsushi’s decision to take in murderous toddler Kyoka Izumi at the end of the last volume of Bungo Stray Dogs in imitation of the same generosity the Armed Detective Agency once extended him leads, as one might have guessed from a series this cliche, to misfortune. Her rescue was something that mafia enforce Akutagawa figured would cause Atsushi to lower his guard just long enough for him to snatch the careless weretiger up. It’s not only that he’s still interested in the bounty on the weretiger’s head: a few carefully chosen words from his one-time mentor Dazai have also stoked the fires of resentment in his mind. He can’t stand the idea that the same man he once so admired, the same man who never once spared him anything beyond censure and insults, would talk so highly of anyone, let alone a bumbler as hopeless as Atsushi.

While Dazai gets into his own battle-of-wits with Mafia boss Chuuya Nakahara and the Armed Detective Agency spends a bit of time floundering on how to find Atsushi before Edogawa’s god-like deductive skills lead them right to Atsushi, creator Kafka Asagiri clearly considers these merely logistical issues. The former is a drawn-out, joylessback-and-forth marred by all of Asagiri’s worst comedic sensibilities; the latter only serves to set-up the clean ending. His real concern is with the budding rivalry between Akutagawa and Atsushi and the pyrotechnics of their climactic clash. The entire back-half of the volume is dedicated to their clash aboard an exploding freighter, the first real fight in a series that sold itself as a battle shonen for nearly three volumes without ever really devoting itself to that premise.

While Dazai gets into his own battle-of-wits with Mafia boss Chuuya Nakahara and the Armed Detective Agency spends a bit of time floundering on how to find Atsushi before Edogawa’s god-like deductive skills lead them right to Atsushi, creator Kafka Asagiri clearly considers these merely logistical issues. The former is a drawn-out, joylessback-and-forth marred by all of Asagiri’s worst comedic sensibilities; the latter only serves to set-up the clean ending. His real concern is with the budding rivalry between Akutagawa and Atsushi and the pyrotechnics of their climactic clash. The entire back-half of the volume is dedicated to their clash aboard an exploding freighter, the first real fight in a series that sold itself as a battle shonen for nearly three volumes without ever really devoting itself to that premise.

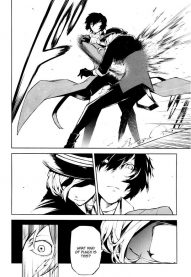

Reading this scene, though, it’s evident that Asagiri’s lack of intention came from a lack of interest. Something about this contrast between these two rivals – their diametrically opposed views on the worth of people, their diametrically opposed sense of purpose and of self – has spurred Asagiri’s first real show of interest in his own series, has finally lent it the purpose he spent the first two volumes not so much avoiding as ignoring altogether, and it shows. There’s energy – dramatic and kinetic both – in this encounter that was sorely lacking in every confrontation until now: Asagiri has gotten brave enough to play with more dynamic panel compositions, even to try his hand at foreshortening and perspective. Finally, the fighters move with some sense of weight, exchange blows that look as if they might actually hurt, look like bodies moving through space instead of ink stains splotched on a flat plane.

It’s almost fitting it took this long for the series to find its purpose, given that protagonist Atsushi has also only just now arrived at his personal reason for fighting on, but this bit of synchronicity seems more coincidence than intentional parallel. The themes that Asagiri is dealing with now were hinted at in earlier volumes but dashed through with such flippancy and treated so lightly that Atsushi’s despair never could feel serious: there was always a stupid joke about Dazai’s suicide attempts to deflate the drama of these moments or a goofy interlude that made even fatal violence seem slapstick. As if the author himself was saying there was no reason to be so self-pitying, that such internal strife was actually worthy of derision, and even then derision without the sting of truth or insight. Your existential angst was so worthless it only warranted slapstick of the lowest variety. Similarly, the rivalry between Atsushi and Akutugawa only feels exciting by contrast with the rest of the story’s empty air: once you realize that it’s barely been built up to does Asagiri’s lack of talent become more pronounced than ever.

Purpose gives a work direction, it gives it confidence and identity, and so is essential, but it’s no replacement for quality execution; nor is it any better a substitute for talent and technique. And Asagairi still wants desperately for both. While he’s pushed himself to come up with new layouts and to play more with spacing and perspective, his art still looks flat even when the moment calls for something bold, something electric. His character designs are still cookie-cutter, his backgrounds without identity. Everywhere you look there is a sameness, a genericness of quality that makes you wonder if the exciting climax is exciting only because it’s surrounded by so little. It’s a doubt that settles even further once you look back: once you recall that there was neither strategy or actual ideological conflict at play in Akutugawa and Atsushi’s conflict – that the latter only won because his regenerative abilities insure that even being gored inside-out by space-devouring shadows is only mildly inconveniencing – you have to wonder if that winning passion wasn’t also a fabrication. If this whole rotten series won’t return to form on the first page of the fourth volume. If it ever “left” that form to begin with.

The introduction of F. Scott Fitzgerald as the villain of the next arc and the man responsible for Atsushi’s bounty does little for my hopes.