It’s Time for Board Games to Take a Stand

In 2013, developer 3909 released Papers, Please. The game, an immigration and customs simulation, put players in the shoes of a border officer charged with approving or denying entry into the fictional country of Arstotzka. Upon release, Papers, Please was hailed as a triumphant work of social commentary, garnering several prominent awards, including the 2014 BAFTA Games Award for Strategy and Simulation. Critics showered the game with praise, calling it a prime example of games as art, proof that games were no longer simply entertainment, but something more substantial.

This War of Mine released to similar acclaim in 2014 and illustrated the impact war can have, not just on the battlefield, but on the home front–an exposé of sorts on the horrors wrought on civilians during times of armed conflict. The game has come to join the ranks of Papers, Please and other titles with a staunch political message in a pantheon of protest, games that reflect their time and use their medium to make a statement. In this way, they can be thought of as digital, interactive versions of famous protest literature like The Jungle or Civil Disobedience.

If video games have evolved to the point where creators are now making political stands a la Upton Sinclair and Henry David Thoreau, then it stands to reason that board games, their tabletop cousin, might be doing something similar. However, a cursory search of Board Game Geek reveals that this is not the case. In fact, aside from an upcoming board game version of This War of Mine, board games seem to be avoiding protest altogether.

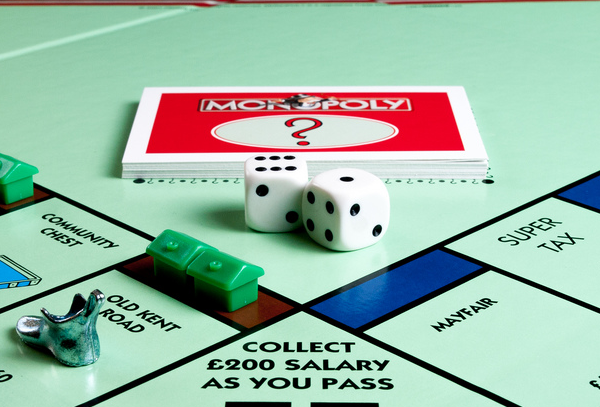

There are two notable exceptions to this admittedly rushed search. One is Monopoly, the perennial family game about real estate. Unwinnable’s David Shimomura wrote about the game’s origins as an anti-landlord protest piece not long ago.

The other example is Brian Mayer’s Freedom: The Underground Railroad. In this cooperative game, players are tasked with helping fleeing slaves to freedom during the lead up to the Civil War. It’s a heavy subject, and one that has caused the game to become regarded as something of a pioneer in a medium that traditionally shies away from a topic like slavery.

Art has, historically, been reflective of the time in which it was created. The aforementioned books and games share this quality with music and film made to open the eyes of the public to unjust suffering. If board games ever hope to attain the same level of consideration in popular culture, designers need to take heed and follow the examples set by the pioneers of other media. Especially now, in this tumultuous time of political uncertainty, it is more important than ever for board games to take a stand. After all, some of the world’s greatest art has been borne of times of strife.

The irony is that war has long been a staple genre of tabletop games, but these games tend to strike a neutral tone, with no commentary one way or the other. Without a true stance, it’s impossible for board games to truly be considered an art of protest.

The horizon is not completely barren, but it is going to take more than a single title for board games to earn the attention and respect enjoyed by protest videogames, film and literature. While we wait for the board game equivalent of Papers, Please, however, we can always put on some Crosby, Stills, and Nash, or read Invisible Man until the cardboard revolution begins.