Binge Watching Making a Murderer, Duty over Escapism

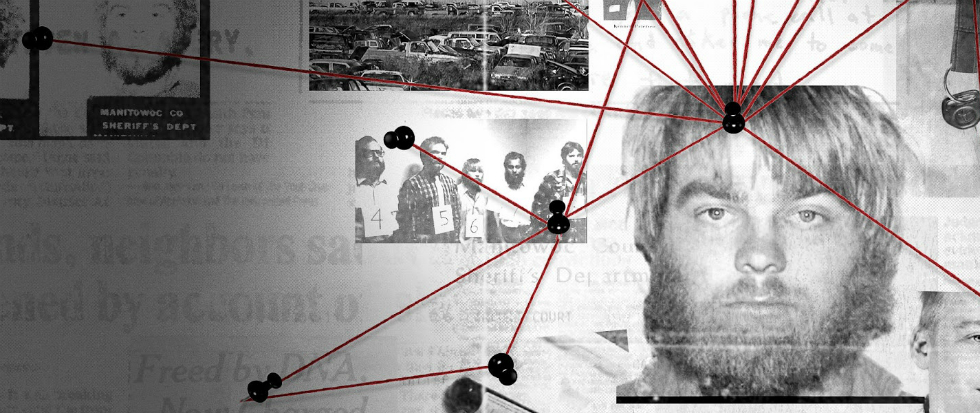

“Binge Watching” television shows on Netflix is typically painted as an indulgent practice, a form of lazy escapism and a short cut to narrative pay offs that used to develop over months or even years. But binge watching Making a Murderer feels more like a duty than an indulgence. As an audience member I felt called to witness what happened to Steven Avery and his family as they grappled with the State of Wisconsin during the murder trial for victim Teresa Halbach. I kept clicking the “play next episode” button not because I was looking forward to seeing what came next, but rather because I felt compelled to “be there” for them, to see this thing through to its end.

Avery, who had already served 18 years in prison for a crime that DNA evidence later proved was committed by someone else, is currently serving a life sentence with no possibility for early release. The documentary follows the trial and subsequent appeals, unearthing disturbing evidence of a potential conspiracy on the part of the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department, who were at the time being sued by Avery for their failures in his previous case.

Many other viewers seem similarly moved, drawing up petitions calling for President Obama to pardon Avery and hounding Prosecutor Ken Krantz’s Yelp page with, shall we say, unfavorable reviews. Krantz, meanwhile, has started making the rounds to condemn the series for leaving out what he says is important evidence that incriminates Avery and Investigation Discovery in partnership with NBC will be airing a special later this month that purportedly “provide critical, crucial evidence and testimony that will answer many questions surrounding Steven Avery.”

But beyond the allegations of planted evidence and coerced confessions (note: to see how frighteningly possible it is to extract a false confession from an innocent person, listen to this episode of The Stuff You Should Know Podcast), some of the most frightening moments in the series are the throwaway comments of law enforcement professionals that demonstrate just how thoroughly divorced they can sometimes become from the ideals that supposedly guide our criminal justice system. Things like a prosecutor declaring that “Reasonable doubts are for innocent people,” or an investigator hired by an attorney for the defense saying about his client and his family “I can find no good in any member [of the Avery family]. These people are pure evil.”

In 1989 Errol Morris’s documentary The Thin Blue Line got Randall Adams released from prison after being sentenced to death (later commuted to life in prison) for the murder of a Dallas police officer. And just last year the podcast Serial got the Innocence Project Clinic at the University of Virginia Law School looking into the case of Adnan Syed.

Will Making a Murderer help Steven Avery, who is still diligently continuing to work through the appeals process without the help of a lawyer? It remains to be seen. But, to me, the most important thing to come out of this series are the haunting quotes and what they imply about how the criminal justice system really works in this country.

Sheriff Ken Peterson declared on the nightly news that the defense’s claim that Avery had been framed by the police was absurd because “if we wanted to eliminate Steve, it would have been a whole lot easier to eliminate Steve then it would be to frame Steve. If we wanted him out of the picture like in prison or if we wanted him killed, you know, it would be much easier just to kill him.”

We might ask on behalf of victims like Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner just how easy it is for the police to target and eliminate someone without suffering any consequences. We might ask how differently things might have turned out for Steven Avery and his nephew Brenden Dassey if they were African American.