Star Trek: The Next Generation – Season 7 – “All Good Things…”

You Were Always Welcome

How do you end a journey that’s never been about a destination?

_____

“For the first six weeks” of shooting Star Trek: The Next Generation, Sir Patrick Stewart says in the documentary Journey’s End, “I literally lived out of a suitcase. I didn’t unpack.” There was only faint hope, in those early days, that the fledgling series would not end up crashing and burning. “Nobody believed that the series would become the success that it did,” Stewart explains in Star Trek: The Next Generation 365. “In fact, one of the reasons that I signed on was that I was assured that the six-year contract that I was signing was meaningless, that the series would do one, perhaps two years at the most.”

Little did he know.

_____

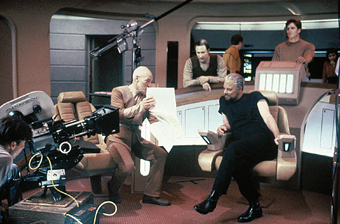

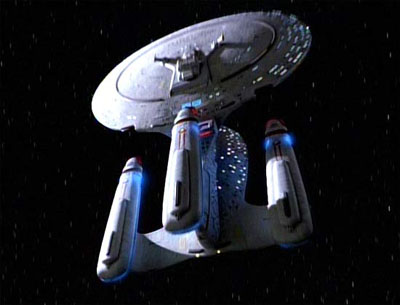

Seven years, 175 episodes and millions of fans later, the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise NCC 1701-D prepared to take their final journey on the small screen. It was a hectic time. In March 1994, the feature-length series finale, “All Good Things…” was being written and shot concurrently with the first TNG feature film, Star Trek Generations. Writers Ron Moore and Brannon Braga were working themselves so ragged they’d forget whether a given scene was supposed to take place in the finale or the movie. The actors were memorizing their lines for the finale while being fitted for their movie costumes. And many resources that hadn’t been pulled away for Generations had been diverted to the new spinoff series, Deep Space Nine.

Seven years, 175 episodes and millions of fans later, the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise NCC 1701-D prepared to take their final journey on the small screen. It was a hectic time. In March 1994, the feature-length series finale, “All Good Things…” was being written and shot concurrently with the first TNG feature film, Star Trek Generations. Writers Ron Moore and Brannon Braga were working themselves so ragged they’d forget whether a given scene was supposed to take place in the finale or the movie. The actors were memorizing their lines for the finale while being fitted for their movie costumes. And many resources that hadn’t been pulled away for Generations had been diverted to the new spinoff series, Deep Space Nine.

It’s a wonder, then, that “All Good Things…” turned out to be one of the most riveting, most emotional and, ultimately, most beloved stories in all of Star Trek.

_____

Here are the essential ingredients, I think, for a satisfying series closer:

1. It has to have callbacks to the past – not only to tug at nostalgia, but also to remind viewers why the time and energy they’ve invested has been worth it, to illustrate how the characters and world have grown and changed. (And, by extension, how the audience has grown and changed alongside them.)

2. It has to provide some glimpse of “what’s next” for the characters, so the audience can picture how their individual lives might unfold.

3. Yet it also has to provide closure, a release of the tension built up not only from its own self-contained story, but from years of these characters’ adventures.

4. Oh, and it’s got to be a good story, in and of itself.

Sci-fi series closers have experienced some notorious whiffs in recent years. Lost’s rambling sixth season led into a finale that felt invalidating to the huge swath of viewers who took the “science” side of the “science vs. faith” debate. Battlestar Galactica’s bizarre introduction of “angels” who persisted for hundreds of thousands of years seemed to betray the gritty, realistic tone the series had cultivated. These finales drew a lot of criticism for feeling like they didn’t capture the spirit of their series.

Spirit, as any Trek fan knows, is essential to this franchise. In its adolescence, TNG had come under fire for its clumsy attempts at capturing the spirit of the beloved original series. “When we first started, the audience was very, very skeptical,” Jonathan Frakes says. “The fear, I think, from talking with fans about it, was that we somehow were trying to re-create what they’d done on Star Trek — and we weren’t.”

Yet by March 1994, TNG had proven as popular, if not more so, than the original series. With a new TNG movie on the horizon, it was imperative to go out on a high note. Trek fans, never known for being silent types, would certainly let it be heard if the finale wasn’t up to snuff.

Luckily, they didn’t have to.

_____

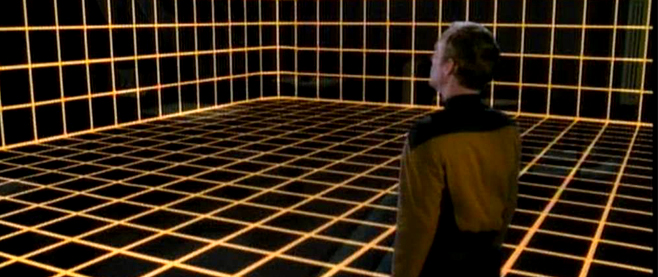

Three timelines converge in “All Good Things…” although they all focus on the heart of the Enterprise – Captain Jean-Luc Picard.

Picard finds himself jumping backwards and forwards in time, embodying younger and older versions of himself. In the past, he finds himself boarding the Enterprise for the first time, escorted by the long-dead Tasha Yar. Twenty-five years in the future, he’s a doddering, cranky old man, tending his family vineyard in LaBarre, France, in denial about the onset of his Irumodic Syndrome – a kind of Space Alzheimer’s. Between jaunts backward and forward, Picard enlists his staff in the present to help him figure out what the hell is happening. The quick cuts between timelines – sometimes occurring mid-sentence – disorient the audience along with Picard. We don’t dwell on any one scene long enough to fall into the common series finale pitfall of sentimentality. Still, while the time-skipping conceit isn’t new to TNG, it’s clear from the outset that this will be a very personal story. It’s not just going to be another mystery-of-the-week affair.

Yet we’ve also got an elegant structure for hitting all the right emotional notes and story beats. In the past, we see Picard in a shuttle, approaching the Enterprise in spacedock for the first time, introducing himself to a crew that he (and we) know so well — but who don’t know Picard, and who don’t yet know themselves. In the future, we see what could be: a VISOR-less Geordi is a novelist who has three kids with his wife Leah (Brahms, perhaps?); Data, affecting a “distinguished” look with a streak of gray in his hair, is a professor at Oxford; and a weary-looking Riker is a Starfleet Admiral who’s been stuck behind a desk too long. Events in the present inform this future timeline, as well: the opening scene introduces the possibility of a budding romance between Troi and Worf, which is paid off in the form of a long-simmering animosity between Worf and Riker in the future. When we learn Beverly Crusher and Picard are divorced in the future, their romantic encounter in the present acquires more weight.

Yet we’ve also got an elegant structure for hitting all the right emotional notes and story beats. In the past, we see Picard in a shuttle, approaching the Enterprise in spacedock for the first time, introducing himself to a crew that he (and we) know so well — but who don’t know Picard, and who don’t yet know themselves. In the future, we see what could be: a VISOR-less Geordi is a novelist who has three kids with his wife Leah (Brahms, perhaps?); Data, affecting a “distinguished” look with a streak of gray in his hair, is a professor at Oxford; and a weary-looking Riker is a Starfleet Admiral who’s been stuck behind a desk too long. Events in the present inform this future timeline, as well: the opening scene introduces the possibility of a budding romance between Troi and Worf, which is paid off in the form of a long-simmering animosity between Worf and Riker in the future. When we learn Beverly Crusher and Picard are divorced in the future, their romantic encounter in the present acquires more weight.

In addition to the time-jumps, Picard also experiences occasional hallucinations. In all three timelines, he sees and hears strangely-dressed figures shouting and jeering at him. His distraction in those moments mirrors ours; as he tries to maintain control of himself in the timeline he finds himself in, he can’t help but grow anxious at the appearance of these phantoms.

It isn’t until 40 minutes into the episode that we learn the cause of all the distress: Q.

Picard finds himself thrown back to the post-WWIII courtroom where he first encountered Q, in the series pilot, “Encounter at Farpoint.” The phantom figures have coalesced into the jeering crowd he remembers from the first time Q put him, and the entire human race, on trial for “savagery.” “The trial never ended,” Q tells Picard. True to his trickster-god archetype, Q claims Picard will be responsible for the extinction of the entire human race – but not how or why.

The of the story becomes a race against time in all three timelines, as Picard must convince each of his crews to head to the Devron system to collapse the temporal anomaly he thinks is causing the disruptions. As he jumps between settings, Picard gradually gains more ability to remember the events of each timeline; his growing confidence mirrors our own, as the disparate settings begin to converge in our minds.

Indeed, the beauty of “All Good Things…” both in script and performance, is how the audience is brought right along on Picard’s quest. In the future setting, we feel his frustration as his erstwhile shipmates doubt his sanity. (Apparently Stewart, who was in nearly every scene in this episode, grew irritated with the documentary crew who’d come to record the filming, and he channels his irritation masterfully in his performance.) In the past, we feel the crew’s hesitation as their new captain issues a string of increasingly bizarre orders. There’s masterful use of dramatic irony throughout. When past-Troi tells Picard the crew is confused and distrusting of his erratic orders, Picard sympathizes that it’s hard to operate in the dark, but adds: “I also know what this crew is capable of…even if they don’t.” We, too, know what this crew is capable of, having seen them coalesce into a family over the past seven years. We get to see that family in action in each of the three timelines, as three different Enterprises converge on the Devron system. In a climactic scene, all three ships are destroyed as they collapse the anomaly.

Indeed, the beauty of “All Good Things…” both in script and performance, is how the audience is brought right along on Picard’s quest. In the future setting, we feel his frustration as his erstwhile shipmates doubt his sanity. (Apparently Stewart, who was in nearly every scene in this episode, grew irritated with the documentary crew who’d come to record the filming, and he channels his irritation masterfully in his performance.) In the past, we feel the crew’s hesitation as their new captain issues a string of increasingly bizarre orders. There’s masterful use of dramatic irony throughout. When past-Troi tells Picard the crew is confused and distrusting of his erratic orders, Picard sympathizes that it’s hard to operate in the dark, but adds: “I also know what this crew is capable of…even if they don’t.” We, too, know what this crew is capable of, having seen them coalesce into a family over the past seven years. We get to see that family in action in each of the three timelines, as three different Enterprises converge on the Devron system. In a climactic scene, all three ships are destroyed as they collapse the anomaly.

_____

Of course, the temporal anomaly is, like so many technobabble artifacts in Star Trek, a giant MacGuffin. Q practically says as much when Picard wakes up back in the courtroom. The point of the Q Continuum’s exercise in placing Picard in this conundrum was to get him to open his mind: to place himself in a paradox and expand his thinking to consider possibilities he’d never considered. This was the goal of the “trial” all along: to get humanity to see that the real exploration would not take place across the galaxy, but within the possibilities of their own existence. The journey has never been about the destination.

But even this philosophical conceit – while beautifully bookending the series – is a MacGuffin in itself. The real focus of “All Good Things…” – and by extension, all of TNG – is how the characters learn, change and grow. Past-Picard knows his new crew will grow into their abilities, even if they don’t; Future-Picard knows he can rely on his old shipmates, even when their lives have taken them vastly different places. The relationships they’ve forged have always transcended the mystery-of-the-week.

_____

Nowhere is this demonstrated more powerfully than in the final scene of “All Good Things…” the very final scene shot for Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Nowhere is this demonstrated more powerfully than in the final scene of “All Good Things…” the very final scene shot for Star Trek: The Next Generation.

As they have so many times before, the senior bridge officers are gathered around the poker table. As Riker, Geordi, Worf, Data, Beverly, and Troi prepare for a hand of five-card draw, Picard enters and asks, somewhat meekly, if he can join the game. There’s an awkward tension in the room; the captain has always stood aloof from these gatherings.

Riker pulls up a chair and Data passes Picard the cards so the captain can deal. There’s a pregnant pause as Picard slowly looks around at his officers, his friends. Patrick Stewart’s simple gesture – meeting everyone’s eyes, projecting the trust and regard he holds for all of them – communicates so elegantly what the audience is feeling: it’s hauntingly bittersweet to say goodbye to these characters we’ve grown to love.

And there’s one final lesson the series has left to teach us: treasure the time you have with your loved ones, even if it means sacrificing your prized aloofness.

“I should have done this a long time ago,” Picard says.

“You were always welcome,” Troi replies.

_____

The second part to the cliché in the title “All Good Things…” is, of course, “…must come to an end.” And yet the episode, and the series, end with a beginning. This seems to be a new Picard, whose travels through time have had a Christmas Carol-like effect on him. He’s more open to expressing his affection for his friends. He’s more open to romantic possibilities with Beverly. And he’s more conscious of their real mission: to expand the frontiers of the mind along with the final frontier of space.

———

Follow J.P. Grant on Twitter @johnpetergrant.