The Knife Mod

1993 was a year of ambitious beginnings. The Trans-Siberian Orchestra was founded and began rocking Christmas. In What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, Leonardo DiCaprio made his debut in a major big-screen role. Square properly introduced the Mana series to U.S audiences with Secret of Mana. And I attempted to create my first videogame.

I was in the fourth grade, and decided that for the 1993 Alexandria Country Day Science Fair, I would create a game for the Nintendo Entertainment System. I had serious moxie at age nine.

Technically speaking, my goal was not to build a game, but to make a mod (a modification of an existing game). This process is how many game designers like me first test the waters. Rather than building a game from scratch, we start from a game that we deem to be a firm foundation upon which to create something new.

[pullquote]What better base to derive a game from than one that was already double derivative? None – none better than Toxic Crusaders, I declared.[/pullquote]

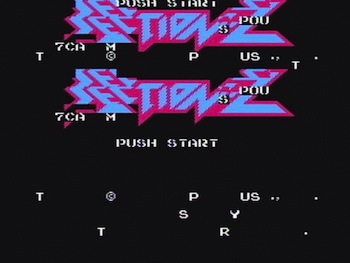

I needed source material for my first foray into game development. So I selected Toxic Crusaders, a beat-em-up based on the short-lived children’s animated series of the same name. That cartoon was itself based on the cult classic film The Toxic Avenger, a hyper-violent superhero spoof from 1984. What better base to derive a game from than one that was already double derivative? None – none better than Toxic Crusaders, I declared.

Here’s the thing, though. At that point in my life, I had no tools available to me with which to mod an NES cartridge. I had neither the hardware, nor the software or any of the programming knowledge needed to copy the game’s source code to my own computer and edit it.

Unwavering, I determined that the best course of action was to plow ahead blindly. After all, I had a plan. I would pry open the plastic casing of Toxic Crusaders and, using powers of intuition honed by years of gaming, use a knife to make strategic scratches on the motherboard. With enough scratch-and-play iteration cycles, I figured, I could alter the game in profoundly artistic ways.

For so many reasons the project was an utter failure. With my first knife incision, I broke the game beyond repair and had to find a new project. I had forgotten all about this catastrophe until recently when, sitting in a pitch meeting, a curious CEO asked me, “Did you always want to make games when you were a kid?” and the memory came rushing back. I told him this story, with all its childish nonsense; he smiled, and then moved on. But for the next few days, I couldn’t.

To process this memory, I sat down and wrote a postmortem of my science fair project. Game developers do postmortems after each game we make in order to look back and analyze our successes and failures, whether the effort ended in a critically-lauded game or a pile of broken plastic. Every project teaches valuable lessons, and a fourth grade disaster is no exception.

Here, for your reading pleasure, is the postmortem document that I wrote:

What Went Wrong

1: I shrugged off good advice.

To begin my production, I approached my chemistry teacher for advice on how to most intelligently shank a complex Nintendo cartridge. It was telling that I sought advice about computer engineering from a chemistry teacher, but at least he knew more about the sciences than I did at that point. His calm, mock-free advice was for me to abort this project immediately. “It just doesn’t work that way,” he warned me. “Why don’t you pick another project?”

To begin my production, I approached my chemistry teacher for advice on how to most intelligently shank a complex Nintendo cartridge. It was telling that I sought advice about computer engineering from a chemistry teacher, but at least he knew more about the sciences than I did at that point. His calm, mock-free advice was for me to abort this project immediately. “It just doesn’t work that way,” he warned me. “Why don’t you pick another project?”

The problem was not so much that I didn’t heed his advice, but that I didn’t process it whatsoever. I should have at least realized that this was a more complicated task than I thought and abandoned my knife-wielding strategy of game development.

2: I didn’t develop the proper knowledge.

I don’t think I had the internet at home in 1993, but one trip to a public library would have taught me that software is written using computers, that hardware engineering is an extremely precise process, and that scratching a game with a knife to change the rules is a fool’s errand. I had an abundance of optimism, and a famine of inquisitiveness.

This was the product of silly associations. I was a straight-A student, but when it came to my favorite pastime, I assumed that making a game would be as simple and magical as playing one. Like an ancient alchemist pursuing the Philosopher’s Stone, I made some haphazard assumptions and ran with them.

3: I ran solo.

Given the tight timeline of this project (a few weeks), I should have considered bringing on a teammate or two. I had plenty of friends who adored videogames. I could have sought out a classmate who had art skills, or perhaps an older collaborator who had taken the fifth grade “Intro to Computers” class. Then, at least, when we found out that the project was doomed, we could have played some Secret of Mana at Trevor’s house.

4: I skipped paper design.

We’ve established that my engineering approach was ignorant and lazy. Let’s talk about my game design process. I did zero work on paper before diving into a development knife fight. It’s funny: years earlier I was designing Mega Man levels on paper and mailing them to Capcom

(something that, coincidentally, my now-Rad Dragon co-designer Mike Sennott was doing at the same time). But the moment I had the chance to work on a digital game I tossed my pen out the window…figuratively.

Paper prototyping is an invaluable tool for game designers. It lets us test out game mechanics before committing to digital development. We  can try a variety of design approaches inside of one day, and get immediate playtest feedback by putting our paper game in front of a few friends. Over a decade later, in my first semester of Graduate-level game design study at USC, we would spend the entire first semester doing nothing but pen and paper work.

can try a variety of design approaches inside of one day, and get immediate playtest feedback by putting our paper game in front of a few friends. Over a decade later, in my first semester of Graduate-level game design study at USC, we would spend the entire first semester doing nothing but pen and paper work.

On top of being good design practice, it would have given me something to show for my efforts. I could have designed my mod on paper and spent a few weeks working on a videogame, instead of quitting and moving onto something considerably less awesome.

5: I knew nothing about my source material.

Man, this is huge. I was editing a game adaptation of a cartoon series, and I hadn’t watched a single episode! While writing this postmortem, I’ve done some research on the show, and discovered how incredibly rich it was in untapped, stupid game design gold. The

Toxic Crusaders game puts you in control of Toxie, the good-hearted janitor-turned-mutant. If I had ONLY watched the damned show, I would have learned about the fantastic cast begging to become alternate playable characters in the game.

Check these out:

Mop: Toxie’s best friend, a sentient mop. Amazing.

No-Zone: A former fighter pilot with mega-sneeze power.

Major Disaster: A military man with the power to control plants. Why was that his power? So great!

Headbanger: A two-headed fusion of a mad scientist and a surfer-dude singing telegram boy who join Toxie and friends for the promise of getting chicks.

Junkyard: A fusion of a homeless guy and his dog. So, naturally, they call him Junkyard.

Yvonne: Toxie’s non-mutant, accordion-playing girlfriend from the Bronx. Who sucks at the accordion.

Sweet holy hell, I missed out.

Now, the flip side:

What Went Right

1: I tried.

Game development is hard work, and a daunting undertaking whether it’s your first game or tenth. Thanks to one part ignorance and two parts ambition, I had the guts to make a videogame for a fourth grade science fair.

Game development is hard work, and a daunting undertaking whether it’s your first game or tenth. Thanks to one part ignorance and two parts ambition, I had the guts to make a videogame for a fourth grade science fair.

Although I failed immediately, I had set out to create something of my own, when I could have gotten away with a much lamer project. (As a point of reference, my project the year before was a report about milk, and how it was good for your bones, glued onto a piece of cardboard. Way to go, third grade Teddy. Way to phone it in.)

2: I was ahead of my time.

Modifying old games wasn’t a new concept for developers in 1993, but for a hobbyist kid it was still a pretty novel concept. One of the early

standout tools, Valve’s Source SDK, wouldn’t be released for another 5 years. I’m not going to say I invented the modern mod, readers. That is for you to say, publicly, on Twitter.

3: I chose a game that was badly in need of improvement.

While this isn’t my personal creative process, I’ve heard some Silicon Valley startup dudes say that a great way to think up a valuable project is to identify a problem in your life and solve it. Toxic Crusaders was the essence of a life problem, in videogame form. It was an extremely stale concept, both in story and gameplay:

Narratively, the Toxic Crusaders TV show was trying to ride the coattails of other eco-conscious cartoons of the decade, like Captain Planet, Swamp Thing, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Well, TMNT wasn’t eco-conscious per se, but it was some sort of cautionary tale about the dangers of toxic radiation to innocent sewer turtles. In gameplay, the NES game was a transparent clone of the TMNT beat-em-up games that Konami had been releasing since 1989, right down to the also-ran skateboard level.

4: I sacrificed.

Through the delusion that my bladed attempt at game development would work, I put something on the line. This was a game that I owned, and enjoyed playing, yet I was prepared to give up my possession (though admittedly not my most prized), in order to perform this experiment.

Game development, like any creative undertaking, requires sacrifice. I may no longer cannibalize games that I own for the sake of our development at Rad Dragon, but I give time, energy, and money to create our games. Back then, time seemed less precious, energy was more abundant, and money was not something I possessed, but I cherished my videogames, and was willing to give one up to become a game creator.

Game development, like any creative undertaking, requires sacrifice. I may no longer cannibalize games that I own for the sake of our development at Rad Dragon, but I give time, energy, and money to create our games. Back then, time seemed less precious, energy was more abundant, and money was not something I possessed, but I cherished my videogames, and was willing to give one up to become a game creator.

5: I learned.

I’m writing this postmortem many years after the project failed, but fourth grade Teddy quickly picked up some of the lessons I’m identifying here. I quit my game development effort that year, but the project I replaced it with – an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine – was a success. I won that damn science fair, and my mom still has my ribbon.

The next year I tried videogame development again. This time around, I studied a little programming and made a work of interactive fiction on my TI-83 graphing calculator. I learned that game creation is a journey that requires study, preparation, focus, and editing in order to make something that’s playable, let alone enjoyable. I don’t have a copy of that calculator game today, but I think it was about magic and robots.

———

Let Teddy Diefenbach know how his knife mod forever changed the gaming landscape on Twitter @TeddyDief.