Agency and Morrowind

Thirteen years old on a Friday night. I was walking through one of the then-plentiful Blockbusters looking for something to watch for our weekly movie night. My mom and I weren’t too well-off and my debut as a teen wasn’t helping the collective household stress. We relied on these weekly bonding experiences to keep us from drifting too far apart.

As I casually wandered over to the gaming section, I started shuffling through the bargain bin.

Project Gotham.

Halo.

Morrowind.

I looked over the box carefully; studying the description.

“This looks pretty interesting,” I thought. “Twenty dollars. I think can swing that.”

I wandered back to where mom was – 80s classics – and got to work buttering her up. Twenty bucks was a lot and I knew it’d be a tough sell.

I offered her uninterrupted access to the computer for a full week. I promised to help her find some more music to pirate and I said I’d only go to thrift stores for the next month. We walked out of the store with Back to the Future Part III and My Favorite Martian – two Christopher Lloyd films – and my used copy of The Elder Scrolls III.

Worth it.

———

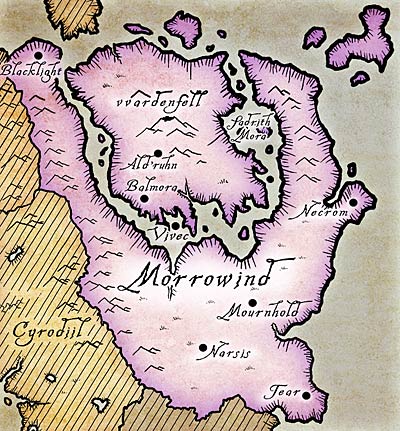

That night, after the movies and kettle corn, I took over the living room TV, hooked up my Xbox and took my first steps into Vvardenfell.

Immediately, I felt there was something different about the game. I was told I was a prisoner being transferred. Nobody told me that I was special. No one held my hand. There was no mystic prophecy about how I would be the one to save the world. Not yet.

I started my journey heading west of Seydan Neen. I fell into the life of an honest thief. Exploring, I found corruption and greed everywhere. Moving through the country side, I stole from and killed those that I thought deserved it, while helping unfortunate people that crossed my path. I freed slaves, punished necromancers and stole from the unscrupulously wealthy – all the while building up my own fortune. After a few hours of this, I began to notice something unique about Morrowind; I found an efficacy, an agency here that I’d never had before. In most games, I was bound to what the developers wanted me to experience.

I started my journey heading west of Seydan Neen. I fell into the life of an honest thief. Exploring, I found corruption and greed everywhere. Moving through the country side, I stole from and killed those that I thought deserved it, while helping unfortunate people that crossed my path. I freed slaves, punished necromancers and stole from the unscrupulously wealthy – all the while building up my own fortune. After a few hours of this, I began to notice something unique about Morrowind; I found an efficacy, an agency here that I’d never had before. In most games, I was bound to what the developers wanted me to experience.

Even in the real world, my access to and participation in the society in which I lived was functionally limited. I stayed home a lot simply because my mom couldn’t afford to spend the money on gas. What little money I earned I picked up through winning trading card games.

Here, in Vvardenfell, I had the freedom to make my own path, to exercise my agency. Still, I turned to a life of crime. I built myself a small mountain of lies; desperately trying to justify my own life of virtual sin.

The next night, after my mom had gone to sleep and I continued my quest. I came to the far side of the island; the ashen plains of the native peoples. There, I was told that I might be the Nervarine – the most recent reincarnation of a Messianic figure to the people of Morrowind.

They said I was going to restore their people and heal the land.

———

Most games thrust that kind of world-saving mission on you. You’re not given a choice, just told that this is what you have to do, and you either follow-through or you quit playing. It falls on the designers to convince the audience that the artificial world is worth saving, or risk pushing players away.

Morrowind took a different route. It loves its players, giving them almost unlimited freedom, and, like a sheepish new lover, expects the player to reciprocate that affection…y’know, if you have the time.

It demands nothing and takes nothing, instead relying upon its own investment. It’s a matter of motivations, you see.

People tend to have hopes, dreams, goals and other people they love and care about. These little bits and pieces are a large part of what makes us, in a very tangible sense, human, that collection of preferences, of quirks, of idiosyncratic traits give us connections to one another. It allows us to share our experiences, build understanding and help us learn to extrapolate and have empathy for people with whom we have nothing in common.

[pullquote]Developers suppose that by simply telling me I should feel one way that I will actually experience that emotional connection.

They’re wrong.[/pullquote]

When weaving an affective narrative, it is the responsibility of the storyteller to help us as the audience understand why any of the characters are doing anything they are doing. When they don’t, we’re left confused, and quite possibly upset, because the story doesn’t make sense without characters that have no believable motivations.

What does that mean for games, then? In interactive media the audience is, by definition, a critical piece of that equation. In games like Morrowind, where the player character is an avatar, the ambitions of the audience and the character are synonymous.

Far too many developers fail to realize this; they fail to link gameplay to narrative and allow an incongruity between the motivations of the player and the character they are controlling. This is the same kind of disparity that Clint Hocking famously brought to light with “Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock.” Most games I play give me, as a player, no real reason to care about anything that is taking place on screen. Developers suppose, for whatever reason, that by simply telling me I should feel one way or another about this or that happening involving some or another character, that I will actually experience that emotional connection.

They’re wrong.

Morrowind gave me something nothing else had up to that point – a sense that I was having a real impact on the game world, that my choices, my input not only mattered but were vital to the game’s narrative.

The fact that I had lined my avatar’s pockets with the coins of the digital denizens around me tied my success to their survival. I could always steal more, but without anyone to buy from, sell to or trade with, much of it was pointless. I needed them as much as they needed me.

I won’t lie and say that I stopped my crime spree in Vvardenfell. It did however, give me some perspective. I was captivated, enthralled by a world that seemed to do away with the quixotic fantasies of the AAA standard.

Here, I had choice. I had control. Morrowind made me feel like I belonged in the world, like I was a valuable piece in their society – even when I couldn’t find one here in the real world.

———

Follow Daniel Starkey on Twitter@DCStarkey. If you enjoyed this, Daniel recently wrote a loosely related story for GameRanx: “My Mother, Commander Shepard.”