He’ll Level This Place

The Air Tokyo jet banked softly, beginning its descent. I was headed to the tiny fishing village of Nishikawa, on the Boso Peninsula on the border of Tokyo Bay. It is literally the last point of the mainland of Japan. From there it was a few small islands and then a very long swim across the Pacific to Hawaii.

My guide and translator, a young college graduate named Taki, led the way as we drove from the airport through the city and towards the village.

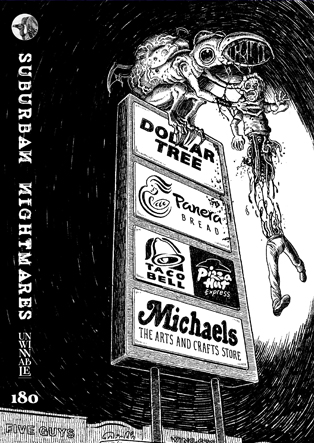

Downtown Tokyo has literally become Blade Runner. Garish neon buildings cutting into the night sky. People living on top of people.

[pullquote]The city of Tokyo seemed to burn for weeks after that. In the glow of the fires lighting up the night sky the Old Man decided he would never visit Tokyo.[/pullquote]

As we drove further from the city, the roads becoming less paved and eventually dirt, Tokyo and the modern age could be felt everywhere; broken apartments and rural huts painted in the glows of a computer or tablet hue.

But I had not come for Tokyo.

I was there to interview a man who lived on the sea for generations. Living off the Japanese mainland, he and his people were the first to ever see Godzilla.

——–

The Jeep we drove in bounced more then steered and my knuckles whitened as my grip on the dashboard became locked. Taki giggled the whole way. The youth of Tokyo have been raised on computer games and to him, this is nothing more then offroad Grand Theft Auto. Outside my passenger window, Mount Daisen rose up, once a formidable volcano capable of leveling but now just second fiddle to every time the big guy decides to stop by for a visit.

We park near a grove of willows and Taki leads me down a dirt path to a line of smooth, dark, overlapping oval rocks. They’re slippery from the ocean air, like marble. We scale the natural barrier and, reaching the highest point, on the other side I find a small strip of land between the rocks and the ocean. There, sitting almost lonely, a small hut.

As we approach, I can see the hut is entirely made of large circular shapes. Taki explains to me that they are Godzilla’s scales, fallen off and collected. Hey, if they can repel anti-aircraft missiles, why not?

From the hut he emerges, a small man, spry with spirit but aged with time. He knew no English and he spoke through Taki. Maybe it was on instinct or years of bad television, but as Taki made the introductions, I bowed.

The Old Man slapped me on the head.

Foolish Westerner.

Why had I bowed? I had no respect nor showed a desire to learn what that bow had meant, to him or his culture.

Why had I bowed? I had no respect nor showed a desire to learn what that bow had meant, to him or his culture.

The bowing incident quickly fading, the Old Man told his tale. He was around 12 when the bomb went off over Hiroshima. Even on this side of the country, he felt it. The volume of all the instant deaths of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was painful.

It wasn’t long after that he was standing knee deep in the ocean (he pointed to an underwater spot not far from the hut) fishing for katsua (a type of tuna). Slowly the water started to rise. He would have thought it was a tsunami except for a sudden wave of fish, of all kinds, that rushed past through his legs to beach themselves. Suddenly, about a kilometer out, the water began to part and the ground made a thudding sound.

Out of the hut, the Old Man’s parents (Mr. and Mrs. Old Man, I presume) screamed. His dog, Shiba, barked and ran up and down the water line.

Godzilla emerged from the water, towering over everything and thundering towards land. The Old Man was too terrified to move as the thing tore itself away from the bottom of the ocean floor, his massive frame temporarily blocking out the sun.

Godzilla simply stepped over him, slamming into the beach, narrowly missing the family hut and moving towards Tokyo. Shiba did not fare so well. Every furry fiber flattened out of existence.

The Old Man pointed and still after almost 70 years later you can see a faded three-toed outline of the print. From there, Godzilla moved on to Tokyo and did not stop until everything was destroyed. And when that goal was accomplished, he returned to the sea.

The city of Tokyo seemed to burn for weeks after that. In the glow of the fires lighting up the night sky the Old Man decided he would never visit Tokyo.

———

He pointed to the line of rocks we climbed to arrive here and Taki began giggling again. It seems the big guy is fine with a diet of fish but after a few dozen humans and a skyscraper or two, he just shits everywhere.

Those aren’t rocks, I’m told. It is petrified Godzilla crap. On knee-jerk reaction, I look at the bottom of my shoes.

Godzilla would return, every few years, always entering land at this point. The military set up detector buoys that would announce his arrival with a loud shrieking horns, but they never lasted long. One visit occurred during the wedding of the Old Man’s sister, nearly crushing half the groomsmen. Once the big guy showed up to fight off a giant moth that decided to pay Tokyo a visit.

The Old Man pointed inland and I looked towards the mountain of Daisen, behind us, and my Western eyes saw nothing. Frustrated, the Old Man scooped up a fallen tree branch and held it in front of one of my eyes. My eyes couldn’t focus on both the mountain and the branch and became blurry. And that’s when I saw, carved into the mountainside, a deep-clawed trench running up from its base. That was, it was explained, from his fourth visit. Godzilla had used the mountain as a kind of springboard to leap deep into Tokyo Bay and eventually level the city.

The Old Man pointed inland and I looked towards the mountain of Daisen, behind us, and my Western eyes saw nothing. Frustrated, the Old Man scooped up a fallen tree branch and held it in front of one of my eyes. My eyes couldn’t focus on both the mountain and the branch and became blurry. And that’s when I saw, carved into the mountainside, a deep-clawed trench running up from its base. That was, it was explained, from his fourth visit. Godzilla had used the mountain as a kind of springboard to leap deep into Tokyo Bay and eventually level the city.

I remember. The alien race, the Simians, had sent down a giant robot Godzilla, a kind of Bender-esque doppelganger, to kill everything. Once again, the true Godzilla rose up from the sea.

It was hard for people. On one hand, he did keep eating the city. But he also saved them from a fire-breathing tin can.

And when the Tokyo populace polluted the waters enough to give rise to the Smog Monster, Godzilla was there and it is then that I see the pattern. The Old Man dabbled his toes at the edges of the water. It is brown and murky. The pollution. It has ruined the waters and killed everything. The radiation from the meltdown a year ago drove everyone away but he refuses to move. He is the last sentinel of his family.

The Old Man’s gaze grew sad, as he looked westward towards the city. He looked at the neon skyline of downtown Tokyo with moist eyes. In the silence between our breaths, the din of the city could be heard.

He’ll be coming back and he’ll level this place again. And with his hand the Old Man made a motion of slice, cutting through the skyscrapers.

He hates it. All of it. It wakes him up. That’s why he comes. It keeps him awake. He comes and levels this place and they just keep rebuilding.

It was in this moment that I understood the Old Man. Through the decades, he had grown a kinship to the big fire lizard. They both longed for quieter, peaceful times. And when things get to a point where he awakens, he appears and crushes it all back to silence. I nodded in the Old Man’s sorrow and he knew I understood.

Godzilla doesn’t hate Tokyo, he just hates being annoyed. And when something pisses him off enough to wake him up, he’s going to roll up some sleeves and wipe the floor with them.

I thanked the Old Man for his time, his answers and mostly his patience. He nodded silently and turned to shuffle back into his hut, and we turned to go.

At the foot of the craggy rocks – excuse me – Godzilla shit, I heard the Old Man’s voice behind me. He had come back out of his hut, running towards me.

At the foot of the craggy rocks – excuse me – Godzilla shit, I heard the Old Man’s voice behind me. He had come back out of his hut, running towards me.

He stuffed something in my hands, a large white hook, nearly cutting me. Only it wasn’t a hook. It was made of some strong ebony material. Taki translated.

The Old Man had pulled this up in one of his fishing nets about 10 years ago. Even as babies, they are born big. And soon grow bigger. I marveled at the tooth in my hand, bigger then my palm.

I instinctively nodded and bowed my head, not as the insulate American upon my arrival, but out of respect. And in return, he bowed back. Taki and I started our journey back up the rock shit, slowly making our way over the hill. I turned back to look one last time.

The Old Man stood at the edge of sea, the water lapping at his ankles, eyes fixed on the horizon. Soon the big guy would be returning, of this I was certain. And he would not be alone.