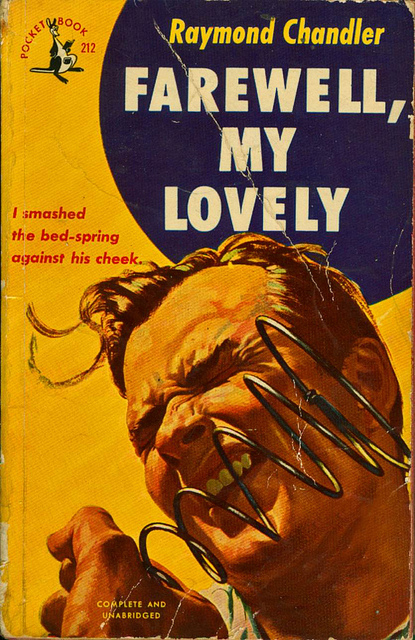

Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely

“It wasn’t any of my business. So I pushed [the door] open and looked in.”

– Farewell, My Lovely

There’s a reason that Jason Schwartzman’s writer character in Bored To Death is reading Farewell, My Lovely when he decides to become a private detective. Since I’ve started writing for money, I have come to identify much more with Raymond Chandler’s enigmatic gumshoe, Phillip Marlowe. Or rather, that I have started to wish I could be him. In my mind, Marlowe is not only a detective, but a freelance writer for hire, someone who investigates stories for a living. And of course, that is what Raymond Chandler is doing: he is using Marlowe to explore a mythical, violent LA – and Chandler commits it to paper.

In The Big Sleep, the book that precedes Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe describes himself: “I’m thirty-three years old, went to college once and can still speak English if there’s any demand for it. There isn’t much in my trade.” Marlowe is well educated. From the way he talks, you can tell he is intelligent and sharp-witted. There’s no need for him to do other people’s dirty work – he could be a white collar man with all the bourbon he desires. And yet, he’s chosen a life of unstructured, underpaid, haphazard work, where he is given little notice to investigate suspicious, cagey strangers and find out their darkest secrets. If you’re a journalist, that might sound familiar. I so wish that I could pace the room with a homme fatale, light a cigarette, and tell him that he “was going to be disappointed in me” with a smug look, like Marlowe would tell his women. But then, if I started that tack, I would never get the interview finished – the person would end up feeling like I had brought them to my house to murder them – and I’d need Lauren Bacall’s looks, besides.

In The Big Sleep, the book that precedes Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe describes himself: “I’m thirty-three years old, went to college once and can still speak English if there’s any demand for it. There isn’t much in my trade.” Marlowe is well educated. From the way he talks, you can tell he is intelligent and sharp-witted. There’s no need for him to do other people’s dirty work – he could be a white collar man with all the bourbon he desires. And yet, he’s chosen a life of unstructured, underpaid, haphazard work, where he is given little notice to investigate suspicious, cagey strangers and find out their darkest secrets. If you’re a journalist, that might sound familiar. I so wish that I could pace the room with a homme fatale, light a cigarette, and tell him that he “was going to be disappointed in me” with a smug look, like Marlowe would tell his women. But then, if I started that tack, I would never get the interview finished – the person would end up feeling like I had brought them to my house to murder them – and I’d need Lauren Bacall’s looks, besides.

Farewell, My Lovely is widely thought of as Chandler’s finest work, not only because he knits three complex crime plots together with absolute mastery, but because it is here that he is most lyrical, his prose making the most stark and ugly terms seem beautiful and worthy. This book is a writer’s book, a book written as a love letter to people who like words. Woven amongst descriptions of dilapidated, worn, alive Los Angeles, are words like this:

[pullquote]It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window.[/pullquote]

“The wet air was as cold as the ashes of love.”

And this:

“I like smooth shiny girls, hardboiled and loaded with sin.”

And this:

“I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country. What I had was a coat, a hat and a gun.”

A coat, a hat and a gun! The end of that sentence is a goddamn bullet. Chandler weaves between refined literary flourishes and cold hard word-punches like Marlowe weaves through traffic. It’s something to marvel at.

Published in 1940, and Chandler’s second novel, Farewell, My Lovely begins when the stoic detective Marlowe is side-tracked from an investigation (as he always is) by his curiosity. He is quickly entangled in the hunt for a missing woman, Velma Valento, and it leads to a maelstrom of dead-ends, seductresses, misdirection and violence, the latter often directed at Marlowe himself. Marlowe barrels along, buying pints of bourbon, with a sturdy jaw and an almost unbelievable immunity to beautiful women.

All in all, Chandler’s writing has had such an impact on me, that when people ask me about myself, I say “I’m twenty-six years old, went to college once and can still speak English if there’s any demand for it.” If there is bourbon near, I gulp it down.

I’ll leave you to the capable voices of Stu and Jenn, who will guide you through the book anew.

– Cara Ellison

———

[pullquote]It was getting to be time for me to put my fist into somebody’s teeth even if all I got for it was a wooden arm.[/pullquote]

After Red Harvest, it took me a little while to get my footing with Chandler’s prose. Hammett’s writing is coiled so tight, with every sentence packing a wallop and a half, that the sudden spaciousness I found in Chandler was jarring. It isn’t bad, though; it’s just very different – more formal, more measured, more writerly. What you lose in fast-paced action, you gain in sense of setting and more complex (though no less ugly) characters.

– Stu Horvath

Right. I don’t think people necessarily realize that about Chandler: it’s impossible to parody his writing, because Raymond Chandler is already hilarious. I thought the part in Farewell, My Lovely when Philip Marlowe watches a pink and black bug walk around on a desk was kind of bizarre, for instance. But then Chandler wraps up that B-plot, and that’s even more bizarre, that he feels a writerly need to get the pink and black bug wherever it’s going.

– Jenn Frank

I don’t want to spend too much time comparing and contrasting Red Harvest and Farewell, My Lovely, (though there are a slew of interesting parallels) but I think it is worth mentioning how the two protagonists are inversions of each other. The Op is brutally efficient, playing the gangsters of Poisonville like a deck of cards for his own vaguely sinister reasons. Marlowe, on the other hand, is pretty much a mug in Farewell, My Lovely. He gets run around, beat up, doped and always seems to be one step behind the criminals. But, while the Op pretends to be a good guy at heart, Marlowe actually is.

– SH

Yeah, Marlowe is this bizarre observer with hardly any agency whatsoever. It isn’t just weird that he takes on cases without knowing anything about them – he does it out of curiosity, I guess? – but stranger still that anybody hires him. He’d be a totally impartial observer, too, if it weren’t for his big mouth. I think what I’m saying is, Chandler’s Marlowe is this hero who doesn’t even solve crimes; rather, he’s an artist on a derive.

– JF

[pullquote]“Will you have some coffee?” I asked. “It might make you human.”[/pullquote]

Or a knight-errant. I read The Big Sleep before Farewell and there is a brilliant bit early on that I think perfectly captures Marlowe (and brings in Brian Taylor’s argument in the last session of the book club about cowboys vs. knights):

The main hallway of the Sternwood place was two stories high. Over the entrance doors, which would have let in a troop of Indian elephants, there was a broad stained-glass panel showing a knight in dark armor rescuing a lady who was tied to a tree and didn’t have any clothes on but had some very long and convenient hair. The knight has pushed the vizor of his helmet back to be sociable, and he was fiddling with the knots on the ropes that tied the lady to the tree and not getting anywhere. I stood there and thought that if I lived in the house, I would sooner or later have to climb up there and help him. He didn’t seem to be really trying.

I have no difficulty picturing Marlowe as an older, world-weary Percival, wandering a corrupt land and resisting its temptations. Weirdly, that would mean the pink fly is the damsel in distress?

– SH

Is he so great at resisting the world’s temptations? Not if it comes in a bottle. I guess – and this is a problem with Chandler, and it extends to his writing – uh, the guy is a total alcoholic. Marlowe uses a bottle of whiskey or gin as a serum, to get people to extend the truth to him. It’s amazing how many people open their desk drawers and, instead of drawing their handguns, pull out a couple little tumblers for drinking. If you read the Chandler Wikipedia, evidently he would only write the conclusion to ‘Blue Dahlia’ if he were allowed to write it drunk. That’s kind of miserable.

And then the real problem with reading Chandler is, you start feeling really tough-and-tumble and putting brandy in your coffee and all that, and suddenly there’s a thirty-page swath you can’t remember reading. So I guess I did a little Philip-Marlowe-mimesis here. I know, I know, I’m not allowed to use the word “mimesis” anymore. Sorry!

– JF

Marlowe is rather soaked in booze, but he isn’t without restraint! My second favorite line in the book is when he tells Mrs. Grayle, “I’m doing what I call drinking,” after she chides him for not keeping up with her (frankly astounding) pace. You’re right though, everyone in this Los Angeles tries to solve their problems with alcohol.

Not that I can talk. I’ve developed a taste for bourbon after reading all this hard boiled stuff…

– SH

[pullquote]I used my knee on his face. It hurt my knee. He didn’t tell me whether it hurt his face.[/pullquote]

Getting back to urban geography…! One thing Cara mentioned to me was how Chandler’s LA is this totally fictional, made-up place. Chandler himself is this weird cultural mish-mash of Chicago, London, and LA (and Nebraska!) and – call me a Chicagoan at heart – his LA is more Chicago than it is Beverly Hills. No wonder he went into screenwriting.

Because of the life P.I. Marlowe has picked for himself, he hangs out with the fringe, the outliers, the down-and-outs, and as such I was surprised (but not too surprised, I guess) by a lot of the racist language in Farewell, My Lovely. I was just really unprepared for that. I keep wanting to say something incisive about the new class tensions in a post-Depression metropolis, but socio-economics has never been my strong suit.

I was most surprised when one character described another as having a “Hitler moustache.” I turned to a friend, pointed the sentence out, reminded him that the book was published in 1940 when Hitler was still alive, and absolutely marveled that we were already calling little tiny patches of moustache “Hitler moustaches,” when they just as easily could have been called Charlie Chaplin moustaches. Reading the book 70 years later, that shouldn’t have tickled me, but it did.

– JF

Chandler’s LA feels real, though. My mom (hi, Mom!) thought the opening scenes at Florian’s felt very New York and I suppose I can see that, but whenever Marlowe strays closer to the Pacific, his descriptions ring familiar. Hills, winding roads, palms. I am pretty sure I’ve driven through Marriott’s neighborhood and spied the Grayle estate from way up on Mulholland Drive (And Grayle, read: Grail. How much more Arthurian are we going to get?)

– SH

[pullquote]His hands went to my neck. Sometimes I wake up in the night. I feel the breath fighting and losing and the greasy fingers digging in. Then I get up and take a drink and turn the radio on.[/pullquote]

I hear that. I read Mrs. Florian as very Chicago, myself, but I can read your mom’s interpretation, too.

Cara alluded to the bit about freelance writing in her introduction, and I remember being struck by that, too. There’s a class thing there, where Mrs. Grayle asks Marlowe about his freelance work, and Marlowe explains he’s done all this by choice, and Grayle wants to know what the money is like. (There’s no money in freelancing, lady!)

So I read that part, and I thought it was so strange – not that Marlowe would pick that type of lifestyle, no, but that Mrs. Grayle would debase herself by putting her head in his lap. And that’s very Shakespearean, isn’t it? I always think of Shakespeare when women go tossing their heads into strange men’s laps. I realize that Mrs. Grayle must find Marlowe very “bohemian,” very “exotic,” that he has so little interest in money and having it, but I was nonetheless surprised when she drunkenly threw herself at him.

– JF

I wasn’t so bothered by Marlowe’s casual racism, by the way. He displayed a nasty streak of violent homophobia in The Big Sleep and, in comparison, his use of racial slurs seems merely procedural. Not pretty, but normal, for the time. It’s no worse than his self-destructive taste in women or his hard drinking. Everything tarnishes, I guess. Even the shiniest of knights.

I wasn’t so bothered by Marlowe’s casual racism, by the way. He displayed a nasty streak of violent homophobia in The Big Sleep and, in comparison, his use of racial slurs seems merely procedural. Not pretty, but normal, for the time. It’s no worse than his self-destructive taste in women or his hard drinking. Everything tarnishes, I guess. Even the shiniest of knights.

– SH

Toward the very end of the book, Marlowe narrates, “He had a cat smile, but I like cats.” Chandler does this all the way through the book, and it’s strange how, for a guy who really does so little to drive the plot – because he just gets swept up, mostly, like the main character in an adventure game, y’know? – Philip Marlowe makes all these groundless, baseless character assessments, where apparently he can just understand another’s motives only by glancing at him. And I guess we’re supposed to trust Marlowe by virtue of the fact that he isn’t dead yet?

But it’s a little like watching a Gordon Ramsay television program, where Ramsay is your palate, and you just have to take him at his word. And when Gordon Ramsay will announce that something tastes like shit, all you can do is trust him on this, because you aren’t there to taste it yourself. You know? And that’s Marlowe: oh, well, he’s the professional; I guess I like this character too. And it’s weird, because I’m used to having an unreliable narrator. Maybe Marlowe is reliable to a fault. He sure gets beaten up enough.

– JF

He definitely got his ass kicked good in this one. He wasn’t too worse for wear in The Big Sleep. In fact, it is funny that this book is the one that inspires Jason Schwartzman to be a private investigator. Marlowe doesn’t investigate much of anything aside of the effects of a serious concussion.

Then again, that’s the main reason why I love Brick. Joseph Gordon-Levitt is death warmed over by the end of the movie. And that’s the point, it’s a function of the corruption. Think of the world of Farewell, My Lovely as an immune system. Maybe that’s why the seedy inhabitants of Los Angeles run roughshod over Marlowe – because he’s a noble infection.

– SH

When Chandler talks about corruption it reads as really contemporary and immediate:

“A guy can’t stay honest if he wants to,” Hemingway said. “That’s what’s the matter with this country. He gets chiseled out of his pants if he does. You gotta play the game dirty or you don’t eat.”

– JF

———

We’ve only just scratched the surface of Farewell, My Lovely. We’ll be talking about it all week in the comments, so if you’ve read the book, feel free to join the discussion!