An Appreciation of Attention to Detail

Ask anyone, and they’ll tell you I have a curiosity-driven partiality for anything Persian in nature. It’s a part of the world so engulfed in turmoil, the crux of many religious origins, ancient far beyond any American definition of the word and in possession of secrets the world may never know. As a child, my favorite Disney movie was Aladdin. In the original Assassin’s Creed, I reveled in playing as Altaïr Ibn-La’Ahad and leaping about through ancient Jerusalem and Damascus. I was always fascinated by the Arabian Nights stories, known officially as 1,001 Nights, which collected Middle Eastern and South Asian folk stories. It is, therefore, no small wonder that the 2008 reincarnation of Ubisoft’s Prince of Persia is my favorite iteration.

There’s good reason that this game feels particularly Persian, but I never realized the extent to which Ubisoft had dedicated itself to the task at hand until I did some research. Already knowing the historical accuracy and detailed attention paid to the Assassin’s Creed series, I have officially come to the conclusion that somewhere up in Canada, Ubisoft Montreal contains a master library, one with rolling ladders and ancient scrolls lit up by candles. This may be slightly inaccurate, but it’s a cool thought nonetheless.

There’s good reason that this game feels particularly Persian, but I never realized the extent to which Ubisoft had dedicated itself to the task at hand until I did some research. Already knowing the historical accuracy and detailed attention paid to the Assassin’s Creed series, I have officially come to the conclusion that somewhere up in Canada, Ubisoft Montreal contains a master library, one with rolling ladders and ancient scrolls lit up by candles. This may be slightly inaccurate, but it’s a cool thought nonetheless.

Prince of Persia draws very heavily from the Zoroastrian faith, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions. It was founded in ancient Iran (Persia) about 3,500 years ago. At the start of the game, the Prince’s beautiful companion, Elika, mentions that her people, the Ahura, have been keeping the evil Ahriman sealed in a “tree of life” for 1,000 years. A thousand years is an interesting number to note because for 1,000 years, Zoroastrianism was one of the most powerful religions in the world. It was the official religion of Persia from 600 BCE to 620 CE. Also, we’ll take a moment to analyze the names of good and evil characters being thrown around here. In actual Zoroastrian faith, the Creator is known as Ahura Mazda but is also known of as Ormazd. The evil side of the coin is actually Ormazd’s brother, not equal in power but craving more authority, cast out of Heaven in a great battle. This “one in every family” was known as Angra Mainyu or Ahriman for short. Thankfully, the game spares us the longer names that game voice actor Nolan North most likely could not have pronounced.

At the start of the game, you find the Ahura have all but abandoned their secluded life in the desert. They have gone out into the world to presumably seek new lives. When our unnamed hero, “Prince,” stumbles into the argument between Elika and her fallen father (who has made a deal with the devil to bring her back to life), he doesn’t even fully believe that Ahriman exists. This is also historically relevant, because despite the initial importance of this religion, it dwindled and disintegrated after the invasion of Alexander III of Macedon and was generally marginalized by Islam by the time the 7th century rolled around. This might give us a general idea of the time period Prince takes place in, based on the hero’s general lack of understanding about Ahriman and Ormazd.

The basic plot devices of the game are to find the four corrupted soldiers of Ahriman – the Warrior, the Hunter, the Concubine, the Alchemist – and restore light to each of the Fertile Grounds.

Zoroastrianism believes heavily in the concept of the restoration of the world and its version of Hell involves punishments that fit the crimes. Souls do not rest in eternal damnation. This is apparent in how Ahriman’s four corrupted have their own areas of domain and yet still have no freedom. Meanwhile, the benevolent followers act through the instrument of “Bounteous Principle,” or the act of creation.

Elika and the Prince also serve critical functions by representing key tenets of Zoroastrian teachings. Elika’s final (and default) character art portrays her with dark hair, wearing a white dress and brown pants, but once you beat the game, you unlock her concept art (which I preferred and found more accurate). In this skin, she has shining white hair, and her garments are almost all white and red. This is representative of The Victorious Helper, who is the Zoroastrian equivalent of the Virgin Mary. In official writings, she enters a lake and miraculously gives birth to a savior who will be present for the ultimate restoration of the world. She is also associated heavily with light. Any form of light is always aligned with Ormazd, whose powers Elika begins to channel more and more in the game. Obviously, her role in the game is to keep you alive and she indeed consistently helps you by pulling you back from near death and assisting in battles. A victorious helper indeed.

Elika and the Prince also serve critical functions by representing key tenets of Zoroastrian teachings. Elika’s final (and default) character art portrays her with dark hair, wearing a white dress and brown pants, but once you beat the game, you unlock her concept art (which I preferred and found more accurate). In this skin, she has shining white hair, and her garments are almost all white and red. This is representative of The Victorious Helper, who is the Zoroastrian equivalent of the Virgin Mary. In official writings, she enters a lake and miraculously gives birth to a savior who will be present for the ultimate restoration of the world. She is also associated heavily with light. Any form of light is always aligned with Ormazd, whose powers Elika begins to channel more and more in the game. Obviously, her role in the game is to keep you alive and she indeed consistently helps you by pulling you back from near death and assisting in battles. A victorious helper indeed.

The Prince in the game is not Elika’s son (that would just be creepy, given their undeclared yet obvious developing romance), but he is definitely supposed to represent the savior figure, known as the Saoshyant. If anything, it justifies his title of Prince. In the final renovation of the world, the dead are revived, and indeed, his last action of the game (pre-DLC, at least) is to bring Elika back from the dead, rerelease all of Ahriman’s soldiers and, eventually, Ahriman himself. The moment the Prince makes this decision, it seems an inevitable endgame is set in motion, leading to the end of times. However, according to official doctrine, at the time of the final restoration, time will end and even those banished to darkness – Ahriman’s four corrupted, for example – will be reunited in their undead form.

The core conflict of the game, and the reason for the decay of the Ahura, results from their King’s loss of personal faith. After the death of Elika’s mother (and ultimately Elika herself), he is a broken man. In his actions, he has let his people become cut off from the world. Elika talks frequently of never having been outside her lands. This is actually completely against Zoroastrian faith, which looks down heavily on all forms of monasticism. It encourages good deeds amongst communities, the growth of family and being a good person overall. It is, therefore, completely believable that the Ahura would have begun to desert their mission to keep Ahriman enslaved because, while it is never said outright in the game, one would imagine there might have been an uprising against their King turning his back on the tenets of their faith. It seems they were on the right track, because he ultimately turns to Ahriman and agrees to free him simply for personal relief of grief, an action that turns him into a madman who is partly responsible for killing again the daughter he initially sought to revive.

Those ending moments when you, the player, are left holding the dead Elika in your arms, staring out into the desert, hearing the whispering of the defeated warriors in your mind, leave you thinking, “What am I to do?” There is an achievement, in fact, for standing for a solid minute with her in your arms, proof that the game built up the pair’s entire relationship and struggles in order for you to have that moral conflict at that moment.

When the Prince ultimately decides it is wrong for Elika to die and undoes her sacrifice, she is furious with him. However, the DLC shows that despite her anger, she resolves to go out in search of the rest of her people to find more to fight against Ahriman, who is now let loose in the world. While it seems that what the Prince has done is blasphemous, he has actually served the Zoroastrian faith better than its so-called followers. He is forcing a soldier of Ormazd to go out into the world to seek others and gather strength.

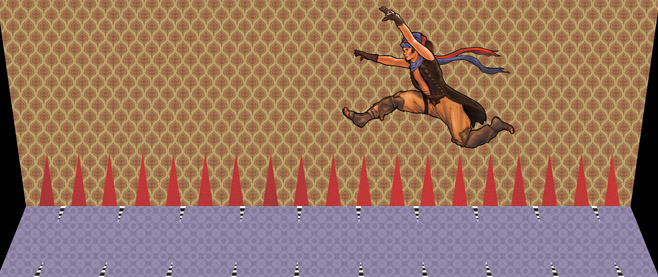

Other details also show Ubisoft’s dedication to inspirational accuracy. The Prince’s headwear in the game, heavily emphasized in the box art, is blue and red. Fire and water are agents of ritual purity and are seen as life-sustaining in Zoroastrian faith. The choice to color those flowing ribbons in such a way was not a coincidence.

Other details also show Ubisoft’s dedication to inspirational accuracy. The Prince’s headwear in the game, heavily emphasized in the box art, is blue and red. Fire and water are agents of ritual purity and are seen as life-sustaining in Zoroastrian faith. The choice to color those flowing ribbons in such a way was not a coincidence.

As if all these details weren’t enough to prove that Ubisoft sought to create a truly Persian experience, the storytelling itself uses methodology that is important in 1,001 Nights. The game begins with a vision of events that ultimately repeat themselves at the end. There is a tale in 1,001 Nights known as “The Ruined Man Who Became Rich Again Through a Dream”. In short, a foreboding dream he has not only predicts his future, but the dream itself is the reason the prediction comes true at all. Similarly, the Prince and Elika share the vision of her father releasing Ahriman to revive her, and at the end the Prince makes the same decision, despite all their struggles, out of the same love for the same woman. Did the vision of one cause the other?

I always knew I loved this iteration of the series most of all, but learning this makes me love the 2008 Prince of Persia all the more. My only criticism is Nolan North’s casting as the voice of the Prince. After all that attention paid, I would have appreciated at least the correct accent for a protagonist so critical to the world’s ultimate outcome. I also would have liked him to be a little less sarcastic. I came to love him, but my initial feelings were, “You’re kind of a cocky little shit, aren’t you?”

Unfortunately, it is still unknown if Ubisoft plans on making a sequel to this strange little grain of sand that stands out so jarringly from the Michael Bay-stylings of the other installments. The only hope for a resolution to Prince’s cliffhanger is from the words of Ubisoft Montreal’s animation director, Jan Erik Sjovall.

He was quoted in 2010 as saying, “I think it was a breakout. It was groundbreaking in a couple of issues … So, it wasn’t an experiment, we tried to truly do something new and unique.” For now, however, to quote the game’s intro monologue, this game remains “Unaware of the world around it. Whirling on the breath of the Gods, at the mercy of the storm that engulfs it.”

I, and many others, eagerly await news that proves otherwise.