2025

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #195. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

Welcome back to the time machine! This month we reflect on the year gone past and how the spirit of revolution never really dies, focusing on a trio of One Battle After Another, Palestine 36 and Happyend.

O1

It’s not hard to be skeptical about One Battle After Another (distributed by Warner Bros, who are set to become part of an industry-wrecking Monopoly, and starring Leonardo DiCaprio who parties with Jeff Bezos). There’s no denying Paul Thomas Anderson’s talent as a writer/director, but a lot of artists who make interesting work with a historical and political bent really struggle to stay as sharp when faced with the realities of the present and near-future. There’s also just a long way between making work that’s critical of capitalism and sharply portraying contemporary revolutionaries. In this case, I was happy to be proven wrong!

P4

At times watching Palestine 36 I felt it was a little too didactic for its own good, leaning heavily into stock characters to tell its story. But maybe it’s needed. Much of the story of Palestinian resistance is comprised of echoes and rhymes and cycles. 1936 is 1987, is 2018, is 2025. So maybe the time for subtlety is long gone, and we need art and speech that loudly declares who is responsible for the horrors, and lets us know there will also be heroes and communities who rise to face that.

H2

These garages used to be red and now they’re painted white. I walk through the backstreets where as a plucky teenager I printed off anti-fascist symbols to sellotape over the swastikas sprayed onto peeling red paint on my route to school (I wasn’t cool or coordinated enough for spray paint). There was a lonely power in it, in taking a little bit of control in the place that both grew you and cut you. Eventually, those symbols were painted over in red and arrow covered papers were blown away. Now it’s all just white.

O2

As Perfidia Beverly Hills couldn’t sleep. She knew she’d have to move soon. She knew she’d gotten too comfortable. People on the streets began to recognize her and her patterns, they’d smile at her and she’d smile back, not out of awkwardness but familiarity. She always knew she had to go when people started letting their kids play with her, when she stopped being the mysterious American lady with the steely look in her eyes and started becoming Patricia or Bianca, or whichever name she was on by now. As she packed her bags, Perfidia knew borders wouldn’t stop what was chasing her, only slow it down enough that she could keep running. When the tired nomad quietly slipped past her sleeping hosts and into her truck, she switched the radio on to keep her company. After a weather forecast of thunderstorms, it told her about an uprising across the border in Oakland. “Soon..” she whispered to herself as she drove off beneath a canopy of stars.

P3

One of the Palestine 36’s most potent scenes is one of its quietest. On a hill at the top of a beautiful landscape, local Palestinian children play football with settlers and their children who are having a picnic. In a lesser picture, it would be the impetus for a simplistic and a vague appeal to the purity of childhood, However, in the context of a film that is so direct about the last near-century of injustices faced by Palestinians, the message is much sharper. It says that things don’t have to be like this, there’s nothing inherent about apartheid and colonial domination. It says that there is no fundamental inevitable clash of civilizations, just an injustice created and supported by imperial powers.

H3

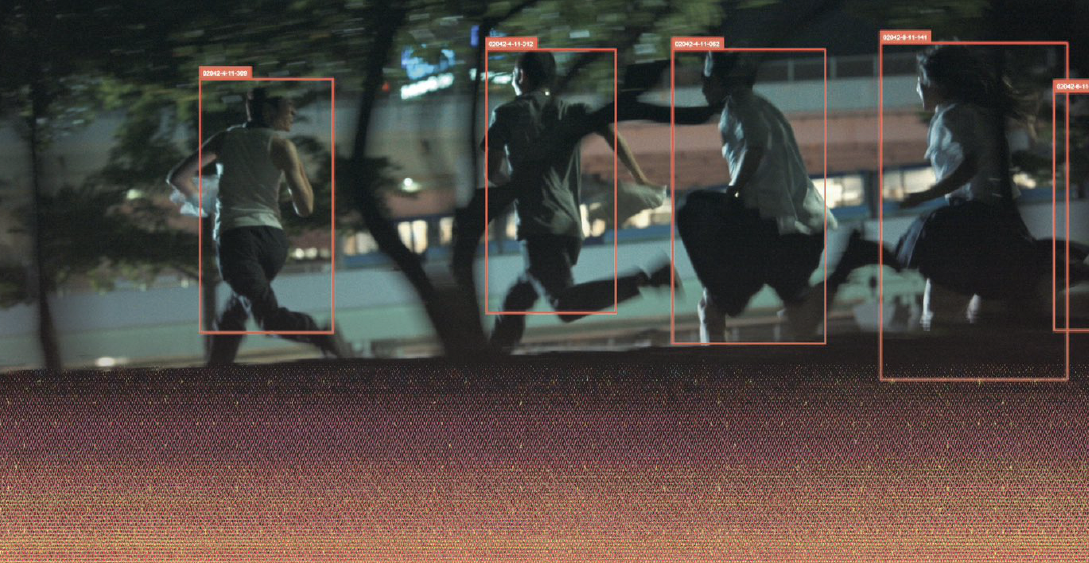

The near-future technologies in Happyend are simple, but effective. The school they all go to has cameras installed in every corner, with each camera cycling round on a big screen displayed to all. If students behave in ways that are disapproved (swearing, kissing, untucked shirts) they get negative points, and with enough negatives their parents get called into the school. All of this runs in parallel with an encroaching military and nationalist presence both in and out of the school. While the work is aimed at the specific social mores of Japan, it is globally true that we have large portions of our lives mediated through opaque algorithms that are increasingly designed to punish and hide nonconformity. What is even more sinister is the way they get us to censor and limit ourselves before an algorithm can do it, just so we can get by. Combine that with so-called artificial intelligence, hardening border regimes and tech monopolies cozying up to politicians, and you get something beyond Foucault’s wildest nightmares.

O3

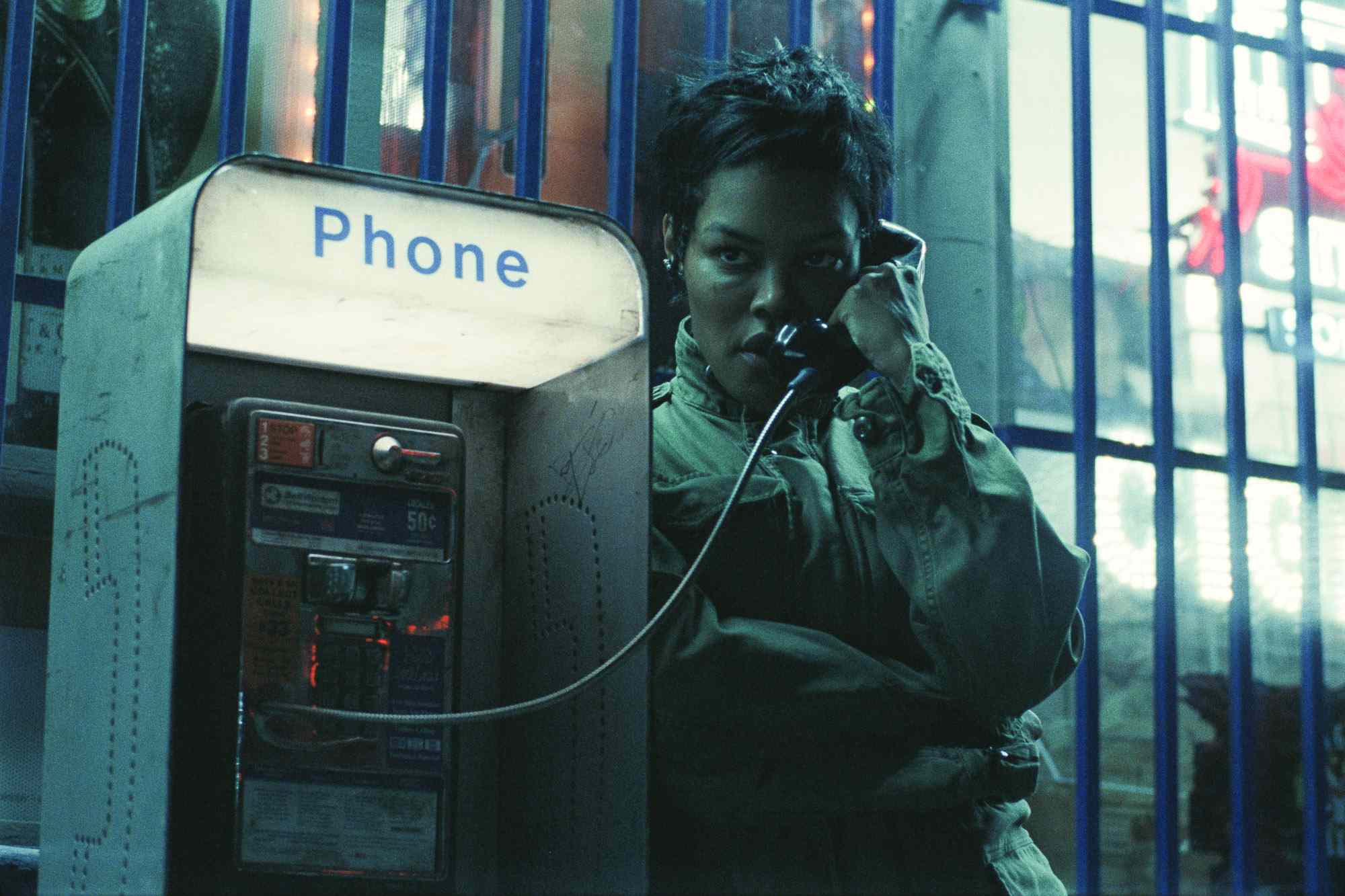

The biggest surprise for me was how fleshy it all felt. Anderson manages to capture how political struggle isn’t just a set of cerebral exercises, it is deeply embedded in the body. He heightens the erotic draw of power to its extremes, and it is undeniably messy, but all the more real for it. At the forefront of this is the inimitable performance of Teyana Taylor as Perfidia Beverly Hills, who uses sexuality as a weapon. Her movements and the camera feel like they’re in a choreographed push and pull, shifting between Perfidia as the master of her sexual embodiment and Perfidia as an object without agency. She never fully gives up her agency, always ready to turn the tables at the last moment, but never reaches the heights of the power she is so intoxicated by. Do revolutionaries act because of the nobility of their spirit or because of their more red-blooded desires? The reality is a sweaty compromise.

P2

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

– Refaat Alreer (1979-2023)

H4

There’s always a risk of rose-tinting your glasses when it comes to reflecting on teenage years. The highs of whatever liberties you took are hard to convert into something more long-lasting, at least without external help. Neo Sora nails that balance with the ensemble cast. Each of them grasps for their own definition of freedom and each gets a bittersweet taste of it, and like every good coming-of-age film no-one is left quite the same after. You hope they’ll carry on some of that rebellious fire – even if it’s not quite as uncontrolled.

O4

While the plot threads can be messy at times, the emotional through core of Anderson’s grand adventure is undeniable, there’s a firm belief in leaving the world a better place than you found it. We know it could be useless! We have failed in these fights before and likely will again. We know it could end badly! But the connections we make during it mean something. The love formed means something. Each glimpse of a better future can thread through to the next generation, and even if they don’t win, maybe the next people will.

P1

In Palestine 36, Annemarie Jacir takes us nearly a century back to the Arab Revolt of 1936-9 in Palestine against colonial rule and specifically Britain allowing the displacement of villages by settlers. She doesn’t take an entirely reverential tone, instead showing the complex dynamics between different elements of Palestinian resistance, particularly how national liberation movements are often hampered by colonial forces intentionally exploiting class dynamics. Even with those wrinkles, Jacir’s film burns with defiance throughout.

H1

Happyend starts with some teens sneaking into a rave by pretending to be barbacks just so they can see their favorite DJ. As surveillance increases in their lives, with some near-future facial recognition and behavioral scoring, they continue to find a way to carve out little rebellious spaces and moments. The stakes are largely on the smaller side of the trio in this piece, but to these irreverent teens every little freedom matters, no matter how small and they’ll fight for every inch of it.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer coming to you live from the British and Irish Isles. You can find her roaming the streets on his bike or at https://tayowrites.persona.co/ if you’re at a more pedestrian pace.