1964

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #193. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

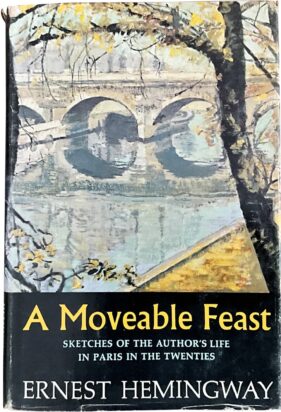

Welcome back to the Time Tour! This time we bring ourselves to a time of deep change in 1964, delving deep into Ernest Hemingway’s posthumous memoir A Moveable Feast, a book of layered griefs and rose-tinted manipulations.

Fractures and Fiction

In this memoir, the way Ernest Hemingway approaches the past is deeply fractured. The book is made of a series of vignettes with recurring people like Gertrude Stein popping up throughout. This is probably fitting for a memoir cobbled together by his last wife Mary Hemingway from manuscripts and notes her late husband had written before his death, drawing on notebooks from the 1920s, that he found in a basement in France in 1956. There have been various versions of this book, and gallons of ink have been given to the question of which version is the most authentic – the version I read was the Vintage 2000 publication which to my knowledge is largely based on the original 1964 publication.

With all that context, it makes sense that this is much more a book of evoking emotional truth than it is about biographical detail, with people, places and chronology all blurring throughout. Beyond that, there are clearly moments which are fabricated for the sake of a good story. I think these blurs are perhaps the most interesting bits, because it tells you so much about not only what Hemingway wanted to remember, but what those he left behind thought was important too.

As Brontez Purnell once said in an interview – “Memoir is fiction” – I feel like this memoir also shows the beauty of how memory is fiction too.

Saint Scott

Hemingway’s writing about F. Scott Fitzgerald occupies one of the longer sections of the book, sitting somewhere between a beatification and an ode to a dead lover. Each of Scott’s neuroses and abrasive elements are forgiven, or at least apologized for. Each quirk and odd lie becomes part of the proof of his undeniable brilliance and purity. He becomes the embodiment of the doomed talent emerging from the interwar period, who so often fell apart whether by alcohol, their own hands, or shrapnel.

It’s hard not to see some less strictly holy motivations slip through as well, when A Moveable Feast has passages like this describing F. Scott Fitzgerald as having a “delicate long-lipped Irish mouth that, on a girl, would have been the mouth of a beauty…the mouth worried you until you knew him and then it worried you more.” In a book that is low on sensuality, this passage is stark in its affection.

By contrast, his wife Zelda Fitzgerald becomes a folk devil. At various points, Hemingway blames Zelda for worsening her husband’s art as well as her husband’s drinking problems which eventually led to his death. While it is certainly true that at points she was cruel to him, most historical writings on their relationship suggest the cruelties difficulties were mutual. Hemingway also says nothing of how she was plagiarized by her husband, or how by the time of writing had died in a fire at the mental hospital where she had been kept after a severe mental health decline. Her tragedy isn’t deemed important enough to get the messianic treatment. In context, Hemingway’s animosity isn’t just garden variety misogyny/ableism, but seems to show a deeply queer long-held bitterness and jealousy fermented with a deep grief.

Hemingway with Women

When Ernest Hemingway writes about his first wife Hadley, every word is dripping with guilt. As a result of this guilty conscience (mixed with nostalgia and garden-variety sexism), he never really allows Hadley to be complex in the memoir. Instead, she is flawlessly passive, with no sense of an internal life on display. Maybe it’s easier to love someone that you never knew, to consign them to a strange not-quite-fiction that lets you blunt their edges. You get the sense that he never really knew Hadley at all.

One interesting detail in the folds of this book is that Mary Hemingway omitted some of the more direct apologies to his first wife Hadley from the book when she put it together, as well as passages which portrayed his complex love for his second wife Pauline (who was his mistress at the time which the memoir covers). With these omissions, Pauline becomes a ghost that haunts the book, and it’s only on the penultimate page that you get an explicit reference to her and the affair that loomed over all that you’d read previously. Given the omissions, that manufactured suspense teeters between genius and deeply frustrating.

It would be all too convenient to use this to imply that the misogyny embedded in how Hemingway talks about his first wife in this book is all down to the meddling of a nefarious jealous widow. But to do that would be sexist nonsense that flattened the texture of the gender politics of his writing.

Hadley and Pauline are also interesting as a counterpoint to the women who don’t fit into his romantic web. In particular, I think about Getrude Stein here who has an obvious influence on Hemingway as a young man. There are echoes of her biting wit throughout his work in general, but especially in A Moveable Feast where so much time is spent making sharp critiques of his contemporaries and their work. There is much to be said about Stein as an enigma, a groundbreaking queer Jewish artist whose influence runs through most modernism. At the same time, she was fervent in her praise of the Vichy regime and a close friend to Nazi collaborator Bernard Fay, with the praise continuing even after France had been liberated from their grip. While her presence in the book is before the Vichy era, her power as a mercurial force of nature shines through, and means that she becomes degendered for Hemingway, thus she is able to have layers that other women (including Stein’s life partner Alice Toklas) do not.

Even though Hemingway doesn’t quite know what to do with them, each woman present in this book (whether in the text or its making) is undeniably influential on him and his work but at the same time, is put through their own narrative prism.

Memory as Eulogy

Eulogies and memory are never simple. Instead, they end up somewhere between a battle and a flowing collaboration. So many different fingerprints are on this book and the lines between influence, edits and outright manipulation are never quite made clear. In her interviews with Alice Hunt Sokoloff, Hadley puts it best herself – “You can’t write a book without calculating.”

Who is the real Hemingway that comes through in this book and its various editions? The adulterer and misogynist? The poor husband manipulated by a seductress? A painfully repressed and lonely queer? The tragic messiah of American masculinity?

What is the real Paris? The one told through the eyes of a not-quite-tourist? Through the semi-fictionalized bartenders and writers? Through collaborating art dealers? Through a librarian?

As I write this, I wonder what lies my memories will tell me about the places and people I’ve been decades later, what lies they’ve already convinced me are true.

Whatever the real Paris of Hemingway’s youth it was long dead by the time he wrote this book. A little over a decade after he and then-wife Pauline Hemingway left Paris, the Nazis invaded France and installed the Vichy government. By 1942, the city which helped build Hemingway was gone, along with thousands of Jewish people who defined the culture which made that era of Paris so unique. There was of course resistance and a continuing counter-culture, but to do that justice goes beyond the scope of this month’s column and Hemingway’s memoirs.

I’ll end this column with one last bit of eulogy/memory/calculation, the opening to the Restored Edition:

“[H]ere is the last bit of professional writing by my father, the true foreword to A Moveable Feast: ‘This book contains material from the remises of my memory and of my heart. Even if the one has been tampered with and the other does not exist’.”

– Patrick Hemingway

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer coming to you live from the British and Irish Isles. You can find her roaming the streets on his bike or at https://tayowrites.persona.co/ if you’re at a more pedestrian pace.