The Limits of Powerlessness: On Silent Hill f

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #192. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We are what we’re afraid of.

———

In this column, I have long been an active advocate of horror games that function as a sort of inverted power fantasy – games like the first Dead Space and early entries in the Resident Evil franchise serve as excellent examples of how placing the player character at a distinct physical disadvantage amps up the scary effect of the experience. When monsters are problems you often can’t solve with bullets, you tend to take your situation far more seriously. I am even an advocate for games where combat is seldom or never an option, such as in Amnesia: The Dark Descent. I remain largely of the opinion that punishing the player for direct combat with powerful enemies is a core part of what makes these games both scary and fun. Recently, however, a game has challenged how I look at combat difficulty and power dynamics in horror games.

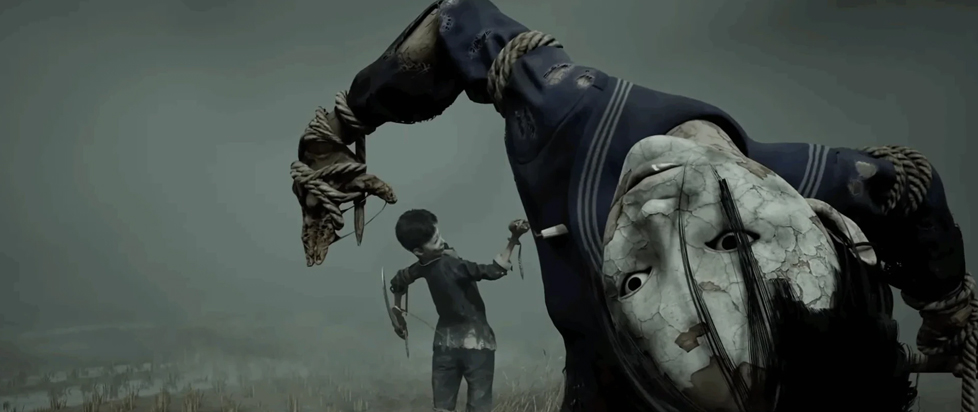

Much like every other horror fan on the planet, I’ve recently been spending a lot of time with Silent Hill f. And before we get into this, I just want to emphasize that I like this game a lot. The narrative and aesthetic choices take the franchise in really exciting directions, and I think some of the newly beefed-up character progression systems are fascinating – there’s probably going to be a future column specifically about the “Faith” mechanic to look forward to. But all other innovations on inventory management and worldbuilding aside, I find myself getting continually frustrated with the way the game intends (or seems to intend, to hedge my bets) for you to interact with the monsters you encounter. Despite an in-game journal entry that specifically tells you evasion is a preferred method of dealing with most enemies, the game belies that sensibility in how the rest of the mechanics are centered on combat. The game appears to want to have it both ways – “run and hide” in tandem with “stand and fight.”

To get into the crunchy bits of the game for a second, SHf has more moving parts to keep track of than any other game in the franchise, which makes sense for the first entry in well over a decade. There are no fewer than five discrete meters to manage at any given time – health, stamina, sanity, focus and weapon durability. All five of these come into play when engaging with an enemy, and if any of them is misused or neglected, you are very likely to die. If you run out of stamina (which you do, fast, since every swing of your weapon and dodge uses some), you become slow and unable to react. If you run out of sanity (which depletes because you’re being attacked by a monster, obviously), you suffer a crushing headache and your character is temporarily stun-locked. And, obviously, the more hits you take, the more your health depletes until game over.

None of these are objectively bad mechanics, but I find their combination fairly exhausting when I try to play the game. It is nigh inevitable that one or more of your meters drops to zero when engaging with a single garden-variety enemy, which typically kicks off a chain reaction – the enemy presses the advantage, and soon all your gauges are red. The game obviously intends combat to be incredibly punishing and thus something to avoid at all costs, which in almost any other setting, I would think is wonderful. Here’s the thing, though: you can almost never actually evade any monster in Silent Hill f. The game is set in a traditional Japanese village in the 1960s, so almost the entire game takes place in narrow alleys, on walkways between rice paddies, or on bridges. There is never more than one path to your destination at any given time, so even though you know the game will punish you for combat, you also have to cross the exact bridge that the monster is standing on. The way the game has set combat up as a mechanical system is entirely at odds with how frequently the game forces you to fight monsters, and so for one of the first times in my life playing a horror game, I find myself continually thinking, “this is so unfair.” And because I think that, the game becomes something that is no longer truly frightening – just frustrating.

Thus, I guess I have to issue a correction for my previous blanket approval of inverted power dynamics in horror games. While I still absolutely adore them, and even see a real pathway to combat being at once punishing but necessary and ultimately doable (Bloodborne is a wonderful example of how you can split this difference, since there is a very distinct cadence to each enemy combat encounter that the player can learn, which is missing from SHf), I also now see that unless this dynamic is very consciously implemented into how players are expected to play, it simply doesn’t work. I will absolutely continue to play SHf because I think narratively and aesthetically there’s a lot on offer, but I think the contradictory ethos of the combat and the world shows what happens when developers delve too far into making their players powerless.

———

Emma Kostopolus loves all things that go bump in the night. When not playing scary games, you can find her in the kitchen, scientifically perfecting the recipe for fudge brownies. She has an Instagram where she logs the food and art she makes, along with her many cats.