Sixty Years Past the Eve of Destruction

Like many Americans my age, I visited my parents over the Christmas holiday. At some point during the visit, my parents and I were driving and talking about the state of the world. Russia still continued its invasion of Ukraine, the Israel/Palestine conflict was escalating, and the USA had just elected Donald Trump (this time by both a popular and electoral majority). Apparently I am in the minority on this, but that struck me as a deeply concerning thing for our country to do. At some point during this conversation, my mom sang out the lyrics, “But you tell me over and over and over again, my friend. Ah, you don’t believe we’re on the eve of destruction.”

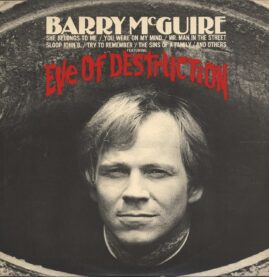

I had never heard these lyrics, despite my mother’s propensity to break into songs from her youth. I instantly questioned, “What song was that?” And so it was that I learned about Barry McGuire and his 1965 hit, “Eve of Destruction.” This song has found its way into regular rotation on my playlists. I learned to play it on guitar. Like most “protest music,” it fascinated me.

It is now 60 years on from 1965, and the world has changed a lot since then. Yet, as I listen to this small capsule of history, I still don’t know exactly how to feel about it. Lyrically, the song is structured as the singer listing out the problems of the day and following up with the chorus of challenging some unseen and unheard optimist who does not believe that our destruction is imminent.

One could quickly dismiss the whole song on the basis that its worst predictions haven’t come true. Hey Barry, it’s been 60 years. We’re still here. We haven’t killed ourselves yet. You were wrong. I find this thinking naive, because there is more to the song than its Vietnam and Cold War era references. If anything, it’s more relevant than ever today.

Listeners from 1965 would recognize that most of the lyrics refer to the Vietnam War. President Lyndon Johnson had campaigned in 1964 under the promise of peace, but was now escalating the conflict in Vietnam and instating the draft, conscripting many young men into military service involuntarily. All the while, these young men had no power to vote (and therefore no legal means of contesting the draft) if they were under 21. The idea of being told you’re old enough to kill or die on behalf of your government but not to vote for it was one that seemed unconscionable.

The image of the button being pressed is an allusion to nuclear war. Only 20 years prior, the first nuclear weapons were developed and deployed in conflict. The power of nuclear weapons was unlike anything previously seen, and before long, the United States and Soviet Union had amassed huge nuclear arsenals. The United States and Soviet Union were at odds after World War II, primarily along the ideological lines of Capitalism and Communism. The two diametrically opposed governments were vying for control of the world, each stocked with enough nuclear firepower to destroy all life on earth. There was legitimate fear that nuclear weapons would be deployed at any given point. The scenarios were endless: accidental launches, preemptive strikes, rogue generals, mistaken retaliation, and so on. There was a very real possibility that everything might end, and it might all be caused by a mistake. There is also an unspoken question: Is all this nuclear posturing doing anything if we’ll all die anyway?

McGuire also clearly expresses his anger with lack of government action on civil rights. While he does not name him explicitly in the song, McGuire likely has Senator Strom Thurmond in mind, whose lengthy senatorial career included many stints opposing civil rights legislation on the grounds of “States’ Rights” (including a record 24 hour 18 minute filibuster against the the Civil Rights Act of 1957). Thurmond was a leader of likeminded Senators who did everything they could to hold up or defeat legislation focused on equality for black people, and McGuire is boiling over with rage at these people.

McGuire uses the song to draw a line between China and the Civil Rights Movement. The Communist Revolution in China was a bloody conflict that ultimately saw the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (more commonly known as Taiwan). Only a year later, China’s Cultural Revolution would see roughly 1-2 million dead. In 1965, marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama were met with violent confrontations by authorities (many of them common people “deputized” that morning) attempting to stop them. McGuire is comparing China’s violent and oppressive history with our own. He challenges the listener: if what is happening in China makes you sick, why isn’t what is happening in Alabama?

McGuire references the Gemini 4 mission that had just happened in June of 1965, and saw astronauts conduct many experiments over four days above the Earth. Here he makes the point that even all this scientific progress was not going to magically make all the problems go away. McGuire alludes to the Kennedy assassination, evoking the drums at his state funeral. Finally, he aims directly at religious hypocrites who would justify bigotry racism believing that being religious would make it all okay somehow.

So, is that it? The Vietnam war has concluded. It leaves behind a checkered legacy in history, but the war itself is over. The United States has never initiated a draft since, even for the now-ended Afghanistan and Iraq wars. The voting age was changed to 18 in 1971 in part due to “Eve of Destruction” being a rallying cry to support the movement. The Soviet Union eventually collapsed in 1991, and none of its nuclear weapons were ever deployed; in fact, there was more nuclear disarmament than deployment. Civil rights have greatly improved when compared with 1965, even despite the best efforts of Strom Thurmond and his ilk.

Things have gotten better, right? McGuire was wrong, destruction didn’t happen. In many ways, things have improved.

As I alluded to at the beginning, the current state of the world led me to discover this song. Things certainly look enough like they did in 1965 for my mother to recall a song from when she was 16. As did my father who was 19, and was in Vietnam with the Army during the war. They see the same uncertain future now they saw back then.

I still don’t know what to make of this song 60 years on. Its message and prediction of imminent destruction didn’t come true. Yet, still it feels we’re approaching destruction again. Should I take this optimistically? Despite threats like nuclear war and global conflict, we made it through and improved things on the way. Or should I be pessimistic? Even 60 years on, it still feels as though we might tear each other apart, and we have a whole new litany of pressing issues. Have we honestly made any progress?

“Eve of Destruction” resonates so clearly now because it concerns more than the material and historical issues it discusses. There is not just our physical destruction on the line, but our moral or spiritual destruction. We may live, but we lose something; we pollute the holy Jordan River with bodies, as the song references. If we proclaim ourselves as a nation of great freedom and opportunity, and then fail at basic civil rights, are we any better than those we would condemn?

Throughout most of recorded history, destruction felt imminent. We always march headlong toward the future, and time stops for no one. In some way, shape, or form, the spectre of our destruction looms over us. We can force it away or turn another direction, at least for a while, but we need warnings like “Eve of Destruction” as a guiding light to reveal the moral pitfalls that could destroy us, too.

———

I owe a great deal of thanks to my friend and Unwinnable contributor Alexander B. Joy for his help in editing a few drafts of this and suggesting Unwinnable as a place to pitch it to.

———

Alex W. DeJong lives in Kansas with his wife, dog, cat, and seven snakes. He is endeavoring to write more about music, religion, gaming, technology, or anything else that catches his interest.